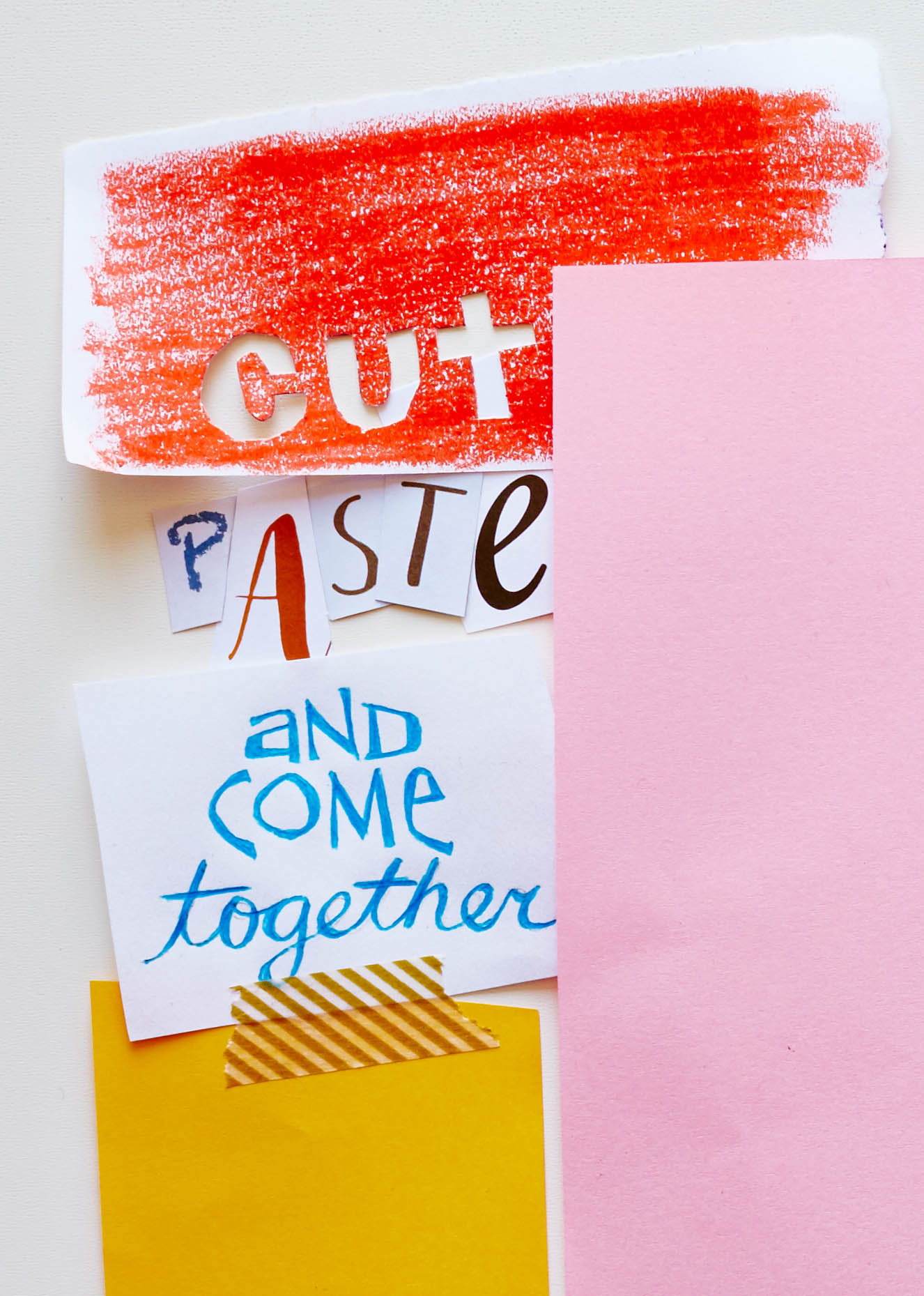

Barnard’s library has a unique collection of more than 10,000 handmade, self-published magazines—known as “zines”—that bring original perspectives to the library’s collection. Though self-published books and pamphlets have been around for centuries, the word “zine” came into use in the 20th century to describe small magazines that celebrate a wide variety of subjects, from the history of Latina punk to musings on the significance of 1970s TV sitcoms. They can be political, literary, personal, or instructional. Sometimes they are collages made with scissors, glue, silkscreens, or stamps. They are typically photocopied, stapled, and published at irregular intervals and in small print runs.

The zines on Barnard’s shelves, stationed in the library in the LeFrak Center, are colorful and inviting, displayed at an angle so the covers are visible. (Most of the zines are acquired in duplicate; one is displayed in the open stacks, the other is preserved in an acid-free archive.) The Barnard Zine Library covers hundreds of topics, with an emphasis on zines by women of color. Last year, the library loaned out close to 700 zines.

Zine librarian Jenna Freedman, who started the library 13 years ago, says, “Zines are primary source documents that tell the story of contemporary life, culture, and politics in a multitude of women’s voices that might otherwise be lost.” Researchers come from around the world—several on grants awarded each year by Barnard’s library—to study the collection because it is an important expression of stories that aren’t ordinarily represented on library shelves. “The voices of people of marginalized identities, for example, are often present in libraries mainly through academic case studies or writing by journalists,” she points out. At the zine library, their interests and opinions are represented by zines on topics such as body image, anarchism, parenting, and Afrofuturism, which combines science fiction, history, and magical realism with Afrocentricity.

Barnard’s zines can be searched by keywords—such as “genderqueer”—that aren’t typically part of the specialized vocabularies used in library catalogs, Freedman says. Outside scholars have used the zines to study black feminism, third wave feminism, and race and media. Students have sought out zines for thesis projects on patriarchy and the riot grrrl movement. Barnard has also hosted the NYC Feminist Zine Fest for the last three years, drawing more than 350 participants this year alone.

Jennie Rose-Halperin ’10, who worked as the library’s zine assistant, helped start the Zine Club—for students to make their own zines—in 2010. The culture of zines is “do-it-yourself (DIY), radical, collaborative, and accessible,” says Rose-Halperin. After Barnard, she went on to earn a degree in library science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, “something I wouldn’t have done had it not been for the zine library.” She now works for Creative Commons, a nonprofit that provides a simple way to reuse and share creative work—“an organization very much built on this DIY, collaborative spirit,” she says.

Vanessa Thill ’13, a fellow zine club member, also remains involved in zine culture as curator at The Knockdown Center, an art space in Queens that hosts events with an emphasis on self-publishing. For Suze Myers ’16, who is studying graphic design at the University of the Arts London, the zine club provided a forum for self-expression and a fun and relaxing break from academic pressures: “It’s a safe space where there’s no pressure to get a good grade—if you make a mistake, you just flow with it.” The zine collection is something distinctly Barnard, Freedman notes: “Girls and women, as well as others, telling their own stories, unmediated."