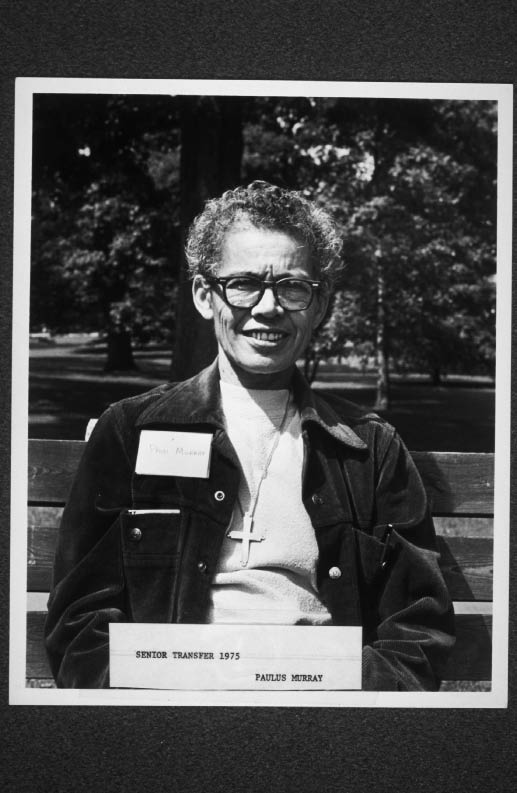

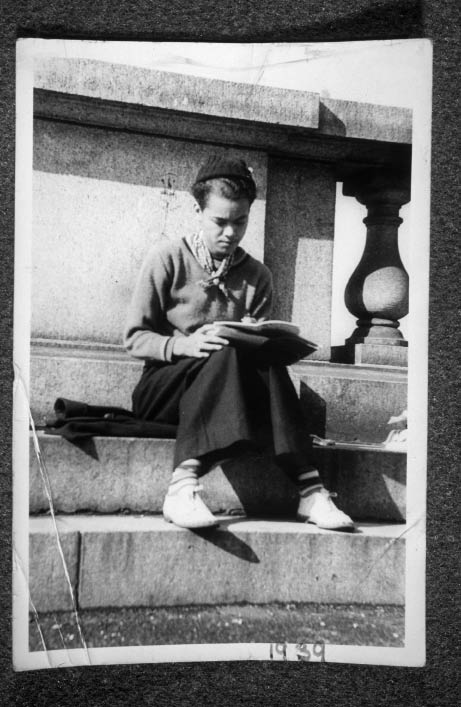

Barnard Magazine introduces you to the faculty interview series conducted by the Barnard editorial team that is available on barnard.edu. In this installment, we speak with Rosalind Rosenberg, Professor of History Emerita, who taught at Barnard from 1984 until her retirement in 2011, about her new biography, Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray. It explores the life, times, and work of this pioneering, gender non-conforming, and largely unsung legal strategist for both the civil rights and the women’s movements. Professor Rosenberg is also the author of Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century, Changing the Subject: How the Women of Columbia Shaped the Way We Think About Sex and Politics, and Beyond Separate Spheres: Intellectual Roots of Modern Feminism.

Professor Rosalind Rosenberg

A Trailblazing Activist and Scholar

Why do people today need to know the story of Pauli Murray?

Living as we are in the midst of a powerful backlash against civil rights and feminism, we need to know the story of Pauli Murray (1910-1985) for at least two reasons.

First, we need historical perspective. Murray’s life demonstrates that today’s backlash and the struggle against it have deep historical roots. They date back at least to the early nineteenth century, when Murray’s maternal grandfather fought against slavery. From him Murray learned that the history of the civil rights movement was one of advances but also of setbacks. As a young child, Murray learned about the post-Civil War amendments that protected the rights of blacks, but she grew up under the tightening grip of Jim Crow. As an adult, she became a lawyer, but her search for work ran afoul of McCarthyism, which took particular aim at blacks, women, and “homosexuals.” Murray’s story testifies to the importance of perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

Second, Murray’s life teaches us that society’s outsiders often have the most important insights. Those outsiders may be immigrants, or they may be native-born citizens who are marginalized by poverty, religion, race, gender, or disability. This outsider status can give them an angle of vision that allows them to see what others cannot. Murray was the quintessential outsider.

You demonstrate that Murray was ahead of her time in the sophistication of her legal thinking, that for years she was strategic in a way that no one else was in challenging race and sex discrimination. You also show that she was ahead of her time in pursuing justice for transgender people. What made Murray able to recognize different facets of discrimination, and solutions to challenge them, when others around her could not?

Murray felt like an outsider, someone “in-between” as she put it, both racially and in her gender. She was darker than other members of her family, who worried whenever she was out in the sun that she would become even darker. At the same time, she was lighter than neighborhood children, who taunted her because of her light brown color. She also felt in-between in her gender—a male born into a female body. Throughout her life she experienced discrimination because of her color and her perceived gender.

In 1938, she applied to the University of North Carolina for graduate study in sociology but was rejected on account of race. Murray was furious. How could the university where her white great-great-grandfather had been a trustee turn her away because of race? When she reached historically black Howard Law School in 1941, she was tormented for being the only woman in the class. Murray was stunned. How could black men who had come to Howard to train as civil rights lawyers fail to see the parallel between race and gender discrimination? She coined the term “Jane Crow” to capture the double discrimination that she endured.

She bested her tormentors by graduating first in her class. Howard valedictorians typically applied and were admitted to Harvard Law School for graduate study to prepare them to be law school professors back at Howard. But Harvard turned Murray down on account of her gender.

Murray suffered, but the torment she endured also inspired her to conceive one of the most important ideas of the 20th century: that the category of gender, like that of race, is inherently arbitrary, with no clear boundaries. When the state deployed either category to subordinate people, it violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution. Over the course of the next three decades she persuaded Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, Betty Friedan, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, among others, that this idea should be used to advance equal rights for all. Murray never spoke openly of her belief that she was what today we would call a trans man, but her belief in the arbitrary nature of gender and racial labels provided the foundation for extending the reach of the equal protection clause to cover gender and sexual minorities as well.

Why do you refer to Murray with female-gendered pronouns (she/her/hers) rather than with male pronouns (he/him/his) or gender-neutral pronouns (they/them/theirs)?

In early drafts, I experimented with the use of male pronouns in writing about Murray in her twenties and thirties, the years in which her sense of self as male was strongest. I then experimented with gender-neutral pronouns such as “ze/hir/hirs” for her forties on. But my efforts ultimately struck me as ahistorical. Murray lived in a gender-binary culture. To use male pronouns for someone assigned female at birth in a time when that was not culturally possible, or to use gender neutral pronouns, I concluded, would undercut the immensity of the struggle in which Murray was engaged and the significance of her contributions.

Murray called out so many discriminatory obstacles, and then she broke through the stained-glass ceiling to become the first African American woman ordained a priest by the Episcopal Church, in 1976. How did her religious commitment and calling influence her social justice activism?

Murray was raised in the Episcopal Church. One of her uncles, an Episcopal priest, took her on the rounds he made of rural churches each Sunday. As a teenager, she visited the bishop of the African-American wing of the Episcopal Church on his deathbed, and he told her that she was a “child of destiny.” These early experiences gave her strength in periods of adversity. As she grew older, however, the ways in which her church fell short of its ideals in its treatment of girls and women nagged at her. She became a priest in part to right what she saw as the church’s wrongs. In her sermons, for instance, she sought to redirect theology toward what she believed to be Christianity’s core teaching: that in Christ there is no black or white, no male or female.

How do you imagine she would respond to Black Lives Matter?

Murray anticipated the Black Lives Matter movement in 1940, when she embarked on a nationwide campaign to save the life of a young black sharecropper, Odell Waller, condemned to death in Virginia by an all-white, all-male jury for killing a white man in self-defense. Murray failed to save Waller from the electric chair, but her crusade brought attention to racial injustice in the American judicial system.

… to “bathroom bills”?

Murray would oppose all “bathroom bills.” In the first half of the twentieth century, signs on public bathrooms in North Carolina, where Murray grew up, suggested that there were three genders: “Men,” “Women,” and “Colored.” If Murray had ever used the one that felt most natural (the one marked “Men”), she would have been lynched—not for gender transgression, but rather for defying state-imposed racial segregation. The North, to which Murray fled after high school, proved only marginally more congenial. The police in Bridgeport, Connecticut, came close to arresting Murray one day when she dared to use the men’s bathroom at a train station. Murray’s race attracted the police’s attention, but her crime that day was in defying gender convention in her choice of a public bathroom. Examining Murray’s life today reminds us that today’s battles over bathrooms—especially the one playing out in North Carolina—provoke fierce passions because they are about more than gender, they are echoes of older (and by no means forgotten) battles over race.

Provost Linda Bell

Women’s Pay in Women-Led Firms

Provost and Claire Tow Professor of Economics Linda Bell discusses her research showing that women in executive-level positions working in “women-led firms” (with a woman CEO who is a director or board chair) see no gender gap in pay. This interview was conducted to mark Equality Pay Day—the date symbolizing how far into the year women must work to earn what men earned in the previous year.

Provost Bell first presented her research in 2005, when she was Professor and Chair of the Department of Economics at Haverford College. “Women-Led Firms and the Gender Gap in Executive Pay” addressed not only the gendered pay gap but also showed that women executives in women-led firms are more likely to be selected for executive-level positions precisely because they work in a woman-led firm. An updated version of Bell’s research, which is forthcoming, continues to show qualitatively similar results.

Using new data from Standard and Poor’s ExecuComp and Institutional Shareholder Services Data, Bell demonstrates that women top executives in public companies earn between 14 and 20 percent less than their male colleagues, based on analysis from 1992-2014. After controlling for firm and individual factors known to influence pay, this difference falls to approximately 3 percent, but is stubbornly persistent and always statistically significant. Similar women executives, working in women-led firms, do not experience a gender gap in pay and have more top women executives than men-led firms, with a 4 to 8 percent greater probability of a woman executive being among the five highest-paid executives in the firm.

For the finance sector in particular, the ramifications of women-led firms are especially notable, since the gender gap in pay in this sector is quite large. Although the gender gap in pay for women in the financial sector is far greater than in corporate firms at large—12 percent after controlling for firm and individual characteristics—the gender gap in pay disappears within women-led firms, and more top executives in these firms are women when compared with men-led firms.

What’s going on here? Is this the impact of women leaders or “women-friendly” firms?

I believe it’s the impact of women leaders. We do know that the impact of women leaders on pay is independent of the gender composition of the board. So these women CEOs are having a powerful and independent impact on promoting gender equity at the firms that they run.

Why does it make a difference for executive women’s pay if a firm is woman-led?

The largest gender gap in pay happens when we compare gross compensation, which includes varied forms of incentive and bonus pay that is more easily manipulated and harder to quantify. Women executives working in similar jobs should not earn less than their male counterparts, but they do. Economists often explain persistent differentials as arising from unmeasured individual characteristics like “work effort” or “commitment.” But to the extent that women executives have faced obstacles in getting to the top of their companies, it is hard to argue that they are different than male executives in their unmeasured characteristics.

What we do know is that women CEOs promote more women and pay the top women in their company comparable wages.

What are the larger ramifications for women in the labor force who are not executives?

The reason this study is so interesting is because individual compensation is a big black box, except that in publicly traded (and nonprofit) companies we know compensation for the top executives. My study sheds light on the fact that at the very top of the wage structure there is a persistent gender gap in pay. We know from sectoral and aggregate statistics that women earn less than men generally, and that the gap in pay has not narrowed all that much in the last decade.

Professor Daniela De Silva

Why Pi Is Bigger Than a Piece of Pie

Associate Professor of Mathematics Daniela De Silva teaches calculus and analysis and focuses most of her research on partial differential equations. This interview was conducted to celebrate Pi Day.

Can we start with a quick math lesson? What is pi and why is it seemingly an endless number?

The number pi represents the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. This ratio is constant, regardless of the circle’s size. The name pi is in fact derived from the first letter of the Greek word “perimeter.”

The never-ending nature of pi is due to the fact that it is an irrational number. (Irrational numbers are those that can be written as a decimal not a fraction, because of their non-repeating, endless digits.) Such numbers cannot be expressed as the ratio of two integers, so no matter how many copies of pi one adds together the answer will never be a whole number. For this reason, the decimal representation of pi contains an infinite number of digits that does not settle into an infinitely repeating pattern. This infinite sequence of numbers is indeed statistically random. That is, it compares to the outcome of infinitely many dice rolls. Curiously, it does contain some sequences of digits that may appear non-random, such as a sequence of six consecutive 9s that begins at the 762nd decimal digit.

What makes pi different from other numbers?

Despite the fact that it appears in many sophisticated mathematical formulas from fields that may seem to have little to do with the geometry of a circle, including number theory and probability, the simplicity of the definition of the number pi is what makes it special. That is why pi was already well-understood by ancient civilizations and even nowadays the approximation of pi from the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes would be good enough in most practical instances!

Professor Peter Balsam

Surviving the Switch to Daylight Saving Time

Daylight Saving Time occurs every year during the month of March, but somehow people are always caught off guard. Professor of Psychology and Samuel R. Milbank Chair Peter D. Balsam explains how everything we think and do relies on coordinated and timed signals between the body and brain.

You have talked about the brain’s role in anticipation. Why, then, are so many of us unprepared for Daylight Saving Time when we “lose” an hour every spring?

When we anticipate meeting a friend in a few hours or anticipate a holiday in a few weeks, we are using timing systems that tell us when important things will happen. These systems are very flexible and let us adapt to the wide range of situations we encounter in different environments. We learn to expect a red light to turn green in a minute or two, and we learn to expect to see an emergency vehicle shortly after we hear a siren. Those are all temporal expectations that we acquire through our everyday experience. We can learn to anticipate best when the signals are reliable predictors of what will happen.

We can anticipate our birthday because it occurs on the same date every year, and by looking at a calendar we get a very reliable cue about when to expect the celebrating to begin. With events like DST that occur on different days every year, we don’t get those same kind of reliable signals. So we have to wait for DST for our bodies to adjust to the change in our sleep patterns and in our exposure to light. Our circadian rhythms adjust to the light in different ways depending on when the extra light occurs. In general, if our day lasts longer when we fly east to west, that is an easier adjustment than in the opposite direction.

What is the circadian rhythm, and how is it affected during DST?

The circadian rhythm is a specialized timer that governs our sleep-wake cycles; the timer has approximately a 24-hour rhythm. It is a very accurate clock, and it is not tied to external stimuli—though some external stimuli like light exposure can shift the rhythm. Knowing that light is coming earlier or later than usual, as we do when we shift our alarm clock for Daylight Saving, does not change the circadian rhythm. Only [actual] exposure to light will change that rhythm.

Professor John Glendinning

Linking Taste Buds and Insulin Release

John Glendinning, the Ann Whitney Olin Professor of Biology, studies feeding and taste, focusing on the role of the modern diet and overeating. One of his areas of research is the link between taste buds in the mouth and insulin release in the gut. In a paper in the American Journal of Physiology, he revealed the connection between a sweet taste pathway in the mouth and insulin release by the pancreas. The paper was co-authored by Yonina Frim ’17, Ayelet Hochman ’16, and Gabrielle Lubitz ’17.

How are taste buds linked to insulin release?

When most of us think about taste, we think about conscious sensations—if you put a potato chip in your mouth, for example, you sense a salty taste. Candy elicits a sweet taste. But what we’re talking about in this paper is a novel sweet taste pathway, which elicits a physiological response—insulin release—but no apparent sweet taste sensation. The response helps us process foods.

What is the significance of your findings?

Scientists previously knew there was a sweet taste pathway that could trigger insulin release from the pancreas and help increase glucose tolerance, but our work gained insight into concrete mechanisms for how this pathway works. There are multiple kinds of sugars—sucrose, glucose, fructose, maltose, lactose—and then there are artificial sweeteners, but we discovered that only glucose activates the insulin release in this sweet taste pathway. We also found that artificial sweeteners don’t activate it.

How could this impact people with diabetes?

Given the rapid rise in incidence of type 2 diabetes, it is critical to gain a more complete understanding of the mechanisms that control insulin secretion. People who have diabetes either produce too much insulin or too little, and that impacts their ability to process sugar. The value of this work is that we know this taste-elicited insulin release can dramatically improve the ability of people to regulate their blood sugar. By understanding these mechanisms, we may be able to help people who are producing excessive insulin by limiting its secretion, or people who don’t produce enough insulin by enhancing its secretion.

For more interviews in the Break This Down series, visit our website.