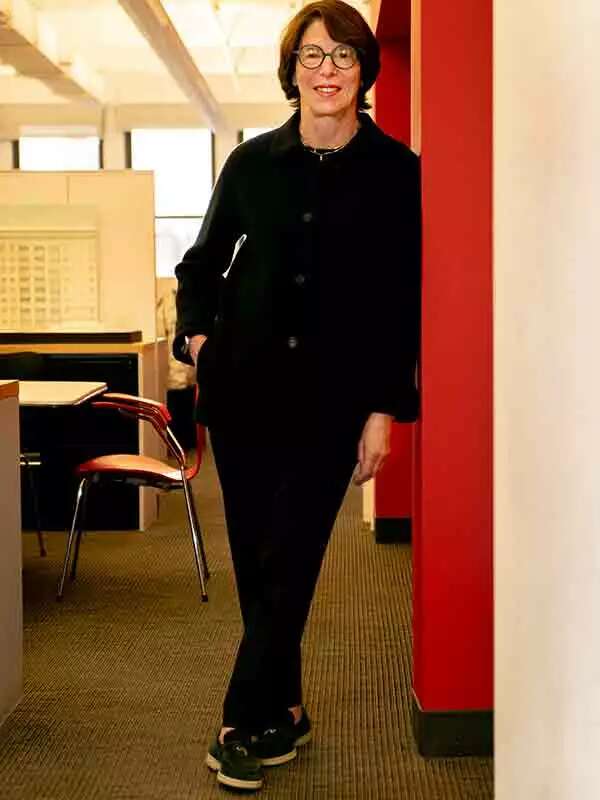

For some, travel represents an opportunity to check off bucket lists, but for Tamara J. Walker, associate professor of Africana studies, it is where history and personal identity collide, particularly in Latin America. “It can sound trite [to say] that travel can change your life,” says Walker, “but I think it does in really profound ways, in terms of how we think about ourselves and what we’re capable of.”

Walker’s love for the Spanish language and Latin American cultures was awoken in the seventh grade. In high school, she spent two weeks in Mexico, which proved transformative. “Spanish was the vehicle through which I became interested in Latin America,” says Walker, who was born to African American parents and grew up in Denver. “Then traveling to Latin America was the path that led me to be interested in history.”

Her interest in language and culture continued through her undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania. She spent a semester studying in Argentina; there, she faced difficulties being Black in a country that felt explicitly racist to her.

“During that semester,” she says, “I started spending a lot of time thinking about why Argentina was so complicated racially.”

When she returned to campus, she began to research race in Argentina, which spiked her interest in the discipline of history, and she eventually earned bachelor’s degrees in both Spanish and history. By the time Walker began her University of Michigan dissertation research in Peru, she relied on the history of slavery to help answer questions about race there, in modern Argentina, and in Latin America more generally. She then taught in the history department at the University of Pennsylvania for seven years and at the University of Toronto for six. Her first book, Exquisite Slaves: Race, Clothing, and Status in Colonial Lima (Cambridge University Press, 2017), won the 2018 Harriet Tubman Prize from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Now, in Barnard’s Africana Studies Department, Walker teaches on diverse topics, such as slavery and gender in Latin America, Afro-Latin American art, and Afro-Latin American history and culture. (She’s the only faculty member in the department with a 100% appointment.)

In June, Penguin Random House published Walker’s newest book, Beyond the Shores: A History of African Americans Abroad, which explores the complex reasons why some African Americans became expatriates throughout the 20th century to present day and how they were treated abroad. Part historical nonfiction and part travel memoir, the book weaves in firsthand experiences to create what The New York Times called “a well-researched account of how global social, cultural and political affairs shaped the conditions for African Americans to travel.”

Deeply personal yet expansive, Beyond the Shores dives into the unknown experiences of well-known and not-so-well-known African Americans who chose to live overseas, creating narratives for the people and characters for the countries. There’s stage performer Florence Mills and France. Agronomist Oliver Golden and the Soviet Union. Author Richard Wright and Argentina. Concert pianist Philippa Schuyler and Vietnam. And many more throughout the book’s eight chapters.

Walker relied heavily on the Black press for research, which she calls “a kind of main character throughout the book for always following the story of Black people leaving the U.S. and sharing their experiences and using those experiences to encourage Black people to go to these other parts of the world.”

But even with the Black newspapers and magazines to draw from, Walker’s research required creative resourcefulness. Some of her subjects had plenty of historical context from which she could pull. Schuyler, for example, whom Walker focuses on during the 1960s, has papers at Syracuse University that contain clippings and journals of her travels to Africa, Asia, and beyond and had also published the 1960 memoir-travelogue Adventures in Black and White.

But for Wright — who barely wrote about his time in Argentina while shooting the film of his book Native Son in that country for nearly a year — Walker imagined themes parallel to her own travel experiences. “He’s someone who wrote a lot about living in Paris and about traveling to other parts of the world, [but] in that chapter, I drew upon my own understanding as an historian of Latin America and what that would have been like for him and for other Black Americans to be there in the late 1940s and to compare that to the United States during the same era,” Walker explains.

It is in this give-and-take of historical research and storytelling that Walker will ground Barnard students. Her goal is for students to imagine history’s long and interweaving arc and to understand how it can benefit from other methodological approaches as well as contribute to other disciplines. “What’s really wonderful about being in Africana studies is being able to sit under that umbrella and have all my work fit under it because it’s all part of my scholarship,” she says. The way Walker sees it, history and travel go hand in hand.

That’s also why in 2009 Walker co-founded The Wandering Scholar, a nonprofit that makes traveling abroad accessible to high school students from underrepresented backgrounds. She hopes to create a similar program that gives Barnard students the opportunity to make their own history-travel connections. The curriculum would allow them to convene with one another before studying abroad and to be in community while they’re overseas. She also envisions them doing research that they can then bring back with them to produce podcasts, documentary projects, videos, and cooking shows.

“More than just traveling, it’s about preparing for global citizenship, for meaningful engagement in issues that are shaping our present and our future,” she says. “And doing it in ways that also allow them to build skills that are going to be [impactful] in their jobs and whatever comes after graduation for them.”

And again, she adds, “I wouldn’t have become an historian of Latin America were it not for my experiences of traveling at an early age to Latin America.”

Illustration by Heather Landis / Photo by Tom Stoelker