In 2021, lifelong community activist Jane Pool approached her Greenpoint, Brooklyn, neighbor and friend Jane Lea ’01 with an enticing prompt: In New York City, where there are so few public spaces and monuments dedicated to women, is there something we can do to address this?

Lea, an architect, was intrigued. She began digging into the research with her team at Lea Architecture, the practice she founded in 2017. “The numbers are fairly shocking,” says Lea, “which you always knew was sort of the case.” She found that only five of the city’s 150 public statues are dedicated to women. Including those five statues, 1.9% of New York City’s monuments and parks are named after women — fewer than one in 55.

It struck Lea and Pool that men’s names are woven into New York’s urban environment, making it nearly impossible not to drop them into even the most casual and quotidian of conversations — “I’m getting on the George Washington Bridge.” “There’s no traffic on the FDR today.” “I’ll meet you at Bryant Park.”

But to Lea, conceiving another single monument or park dedicated to one woman or even a group of women seemed like an empty gesture. Couldn’t we come up with a system that’s much more local and, at the same time, pervasive and grand, she thought? Lea wanted to honor the women whose invisible labor had helped shape the city’s micro-communities and neighborhoods, driven social change, and led movements. She and Pool wanted to leave a narrative trace — in a city where transience is the only constant — of what came before. “There were people who were involved in the transformations of our neighborhoods, like Greenpoint, or defending those transformations, and most of them were women,” says Lea.

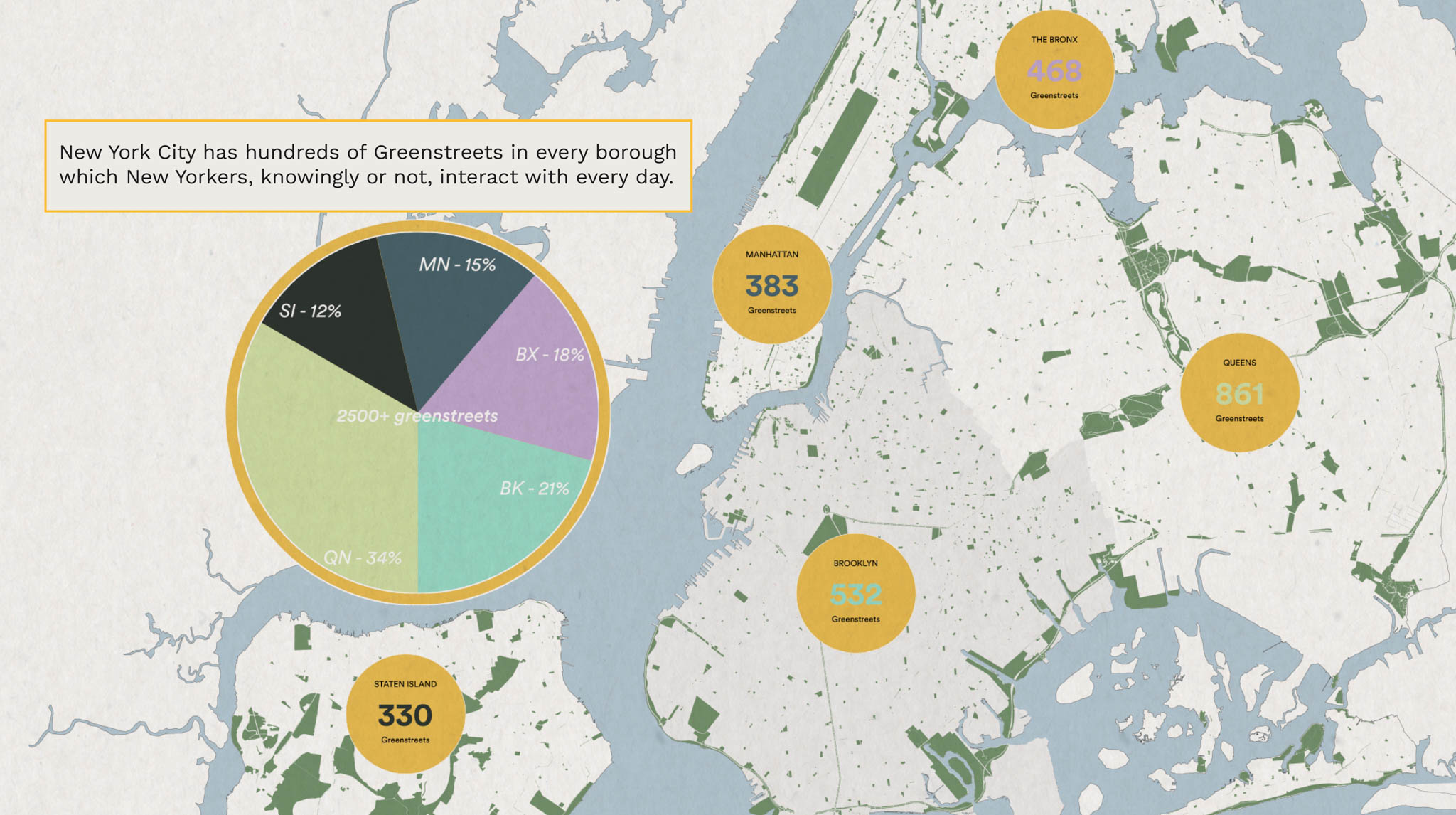

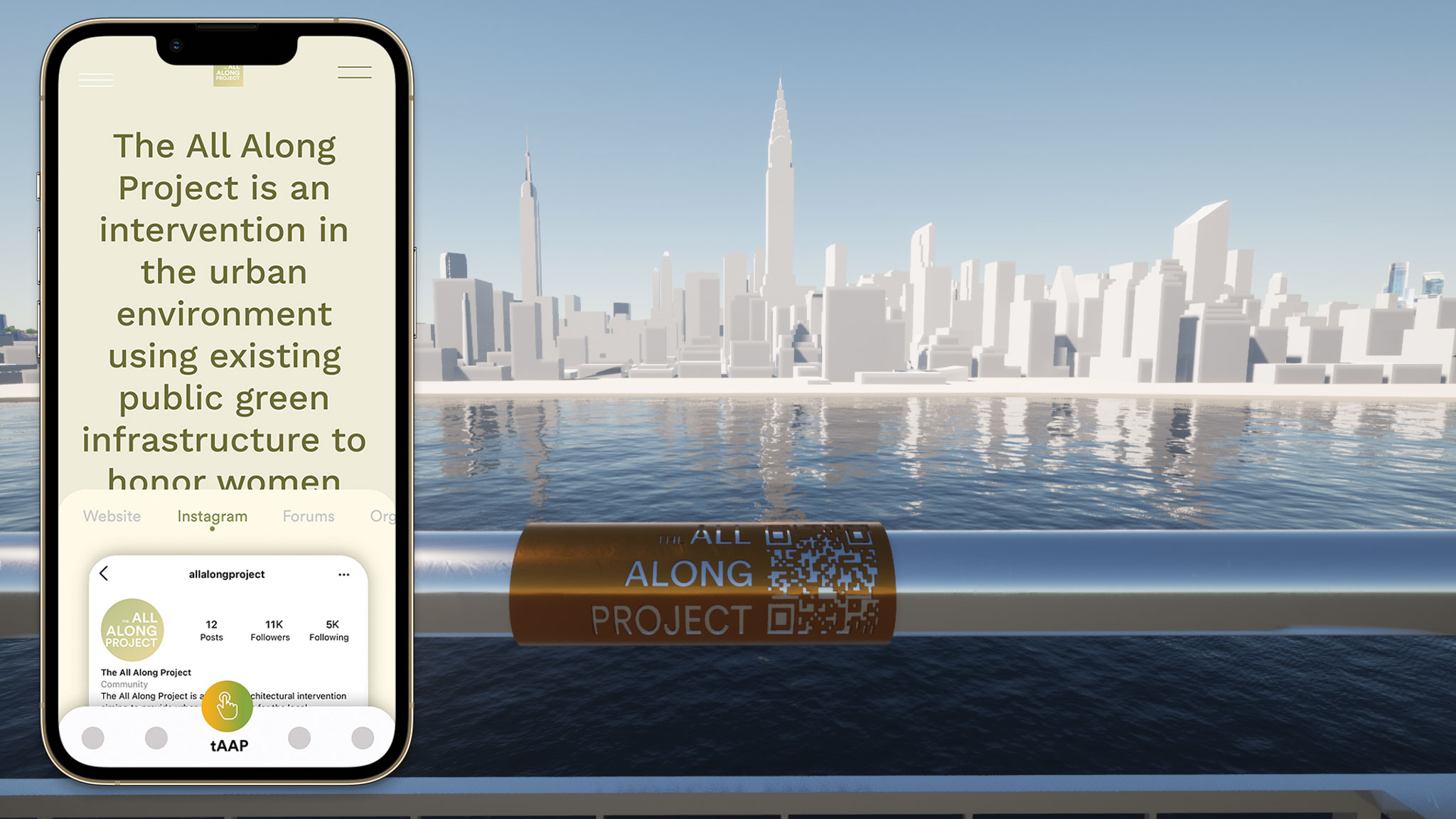

So, rather than a single monument, Lea devised an initiative — the All Along Project — that is both easily deployable and replicable. She and her colleagues designed a system of sleek, streamlined markers, including sidewalk pavers, railing plaques, and free-standing signs, that are embedded with a QR code. Accessing the code leads passersby to a website where they can read a biography of the woman being honored in that spot, as well as connect to a map and interactive timeline that includes other honorees. In New York City, the markers can be embedded in the city’s Greenstreets — paved, vacant traffic islands and medians transformed by the City into green spaces filled with trees, shrubs, and groundcover — and Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) without interfering with access to nature and moments of respite. “[These areas] seem ripe for having another layer of significance,” says Lea.

Lea wanted to honor the women whose invisible labor had helped shape the city’s micro-communities and neighborhoods, driven social change, and led movements.

Lea and Pool have already been in talks with the New York City Department of Transportation and the Parks Department, developers such as Two Trees and Lendlease, and major foundations about rolling out the project. With the support of the North Brooklyn Parks Alliance, they hope to soon install a yearlong pilot of All Along adjacent to McCarren Park, on the border of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg and Greenpoint neighborhoods. They are also forming an advisory committee and a nominating committee to help research and choose the women who will be honored.

But Lea doesn’t want to decide who, specifically, is honored. “We can provide the toolkit. I don’t need to be the author everywhere,” she says. “It could be a model for any community that feels they need more representation.”

One of those women might be Sister Frances Kress, who, in the early 1980s, made it her mission to clean the polluted Newtown Creek, a 3.5-mile tributary of the East River that forms a border between Brooklyn and Queens. In the 1800s, the waterway supported ships for commerce as well as clean water for swimming and wildlife. By the mid-20th century, surrounding refineries, factories, and wastewater plants had made it a toxic dumping ground.

As the Washington Post reported in September 1982, Kress, then a 67-year-old teacher, testified in Washington before the House Subcommittee on Water Resources, pleading with its members to save and strengthen the 1972 Clean Water Act. It could be Kress’s story that visitors come upon when they visit MASE Park, near the mouth of the creek. On the shortlist of potential women to include in the project are two influential Barnard alums: the leading suffragist Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (Class of 1916), who became the first Chinese woman to get a Ph.D. in economics, and Betsy Wade ’51, the first woman to edit the news at The New York Times.

But Lea doesn’t want to decide who, specifically, is honored. “We can provide the toolkit. I don’t need to be the author everywhere,” she says. “It could be a model for any community that feels they need more representation.”

The All Along Project isn’t a diversion from the ethos of Lea’s practice, which, she notes, takes on more pro bono work than her bookkeeper or husband would like. She is also a founding member and the treasurer of Design Advocates, a nonprofit network of design and architecture experts, launched at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, who pool their expertise and offer pro bono services to organizations and communities in need. “I’m interested in making the city a better place and being invested in the outcome of the world around me,” says Lea. “I think that architecture can really transform spaces; on a civic and institutional level, it can be transformative.”

Although Lea grew up in rural Pennsylvania with a homebuilder father and an interior decorator mother, she never considered a career in a design field. Lea was studying sociology and environmental science at Sarah Lawrence College when her twin sister encouraged her to try a summer career discovery program in architecture. Lea recalls realizing she had found her calling: “Oh, I love this; I could do this forever,” she thought. “I like to draw, I like to make models, design things, but overall, I really love working with people a lot. I don’t want to be in a lab by myself. I’m a pretty social creature and also really enjoy collaboration.”

Lea was then diagnosed with cancer, forcing her to take a semester off her sophomore year. When she was well enough to return, she wondered what, exactly, she was returning to. An adviser encouraged her to transfer to Barnard, whose architecture program houses all the undergraduate architecture studies for Columbia University and its partner institutions. “The thing that I find most important about dealing with disappointment and disruption is how you’re moving on. It made me make a decision I might not have been brave enough to make otherwise,” she says. Following graduation, Lea worked for the architect Celia Imrey and then a residential architecture firm in Queens before returning to 116th Street to earn her Master of Architecture at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation.

After working for various New York-based architecture firms for a decade, Lea decided to open her own studio. Her two children were young, and she was able to be at home while slowly building her practice (and teaching at the Pratt Institute and Cooper Union). Now, she and her four colleagues (the studio will soon add another couple of designers) manage a range of projects, including a new railroad station in Pennsylvania, a computer center and other improvements to St. Ann’s School in Brooklyn, and a nonprofit campus, also in Pennsylvania, for people struggling with addiction and behavioral challenges. “We like to solve the problem. A new project has to hit two of three marks: make money, a client we really want to work with, or a typology we really want to explore,” says Lea.

In a field that is known for its long, grueling hours, Lea prioritizes a work-life balance. She lives a block away from her studio and makes time to take her kids to activities like soccer and hockey practice. Lea also gives her team flexibility and the breathing room to live their lives — a privilege she wasn’t always granted at other firms but one she says is as deeply important as the work they do.

She says her staff jokes with her that she’s recognized everywhere they go in Greenpoint, which is even more true for All Along co-founder Jane Pool, she notes. Maybe one day a sign will mark their contributions to the neighborhood.

But for Lea, the collaborative process is what undergirds the project. “The power is not the project itself,” says Lea, “but the community deployment of the project. I think it’s nice for people to be able to self-recognize. And I think that that is a map and marker of a history. It’s a nice record, it leaves a good trace.”

Photo illustrations and graphics courtesy of Lea Architecture / Photo by Tom Stoelker