In 1968, students around the world rose up: In France, Germany, Mexico, Japan; even in countries ruled by dictators, they picketed, occupied, performed political theatre in the streets. It was a trend, a movement, an earthquake. It was, however it was termed, a phenomenon.

In Morningside Heights, on both sides of Broadway, tensions that gave rise to April and May protests had been brewing for years. Amidst the sexual revolution, Barnard students were frustrated about rules that restricted whom they could live with and who could visit them in residence halls. African American students and their allies were increasingly dissatisfied with University policies they saw as racist. The United States’ growing involvement in Vietnam and Columbia’s participation in military programs resulted in mounting opposition, led by groups including Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

What followed that spring—complete with a fiery debate over cohabitation, the occupation of several Columbia buildings, what a Washington Post writer termed a “police riot,” and even a visit by the band The Grateful Dead—was transformative for many students. For others, these events diminished their College experience. Still, no matter where one stood—among the protesters or among those put off by them—one thing was for sure: The events of spring 1968 changed Barnard and they changed its students, forever.

Mounting Tensions

That spring, Barnard students were frustrated by the extent to which the College exerted control over their personal lives. Though Barnard’s administration was more socially liberal than those of many women’s colleges, it still imposed restrictive curfews in residence halls and even stricter limitations on male visitors. Living off-campus with a boyfriend was strictly forbidden. But there was a loophole for students willing to lie on their housing forms: They could say they had live-in babysitting jobs, the one form of off-campus housing Barnard would accept for students living too far from home to commute. To live with her boyfriend, at least one student, Linda LeClair ’71, did just that. Her story soon galvanized much of the campus community.

At the same time, African American students were growing increasingly upset with persistent racism in American society broadly and in Morningside Heights in particular. Prior to the civil rights movement, their numbers had been small, not more than five per Barnard class. Now, an active admissions recruitment effort meant there were about fifty black students at Barnard in the spring of 1968. That increase, paralleled at Columbia, enabled African Americans to form their own campus social life for the first time, including, in 1965, organizing the Students’ Afro-American Society (SAS).

Michelle “Shelly” Patrick ’71, an African American debutante from Detroit, took part. Arriving for Barnard Orientation in 1967, she surveyed the card tables advertising extracurricular activities that lined Columbia’s College Walk, thinking she might join SDS. But an older black student tapped her on the shoulder, saying, “Oh no, dear, you belong over here,” at the SAS table; she signed up. Patrick’s new roommate, Ruth Stuart, also a debutante, but from a wealthy white family in Boston, did not share Patrick’s liberal views. But Patrick, delighted to have a roommate, found Stuart to be “sweet” and decided that they would just not discuss politics.

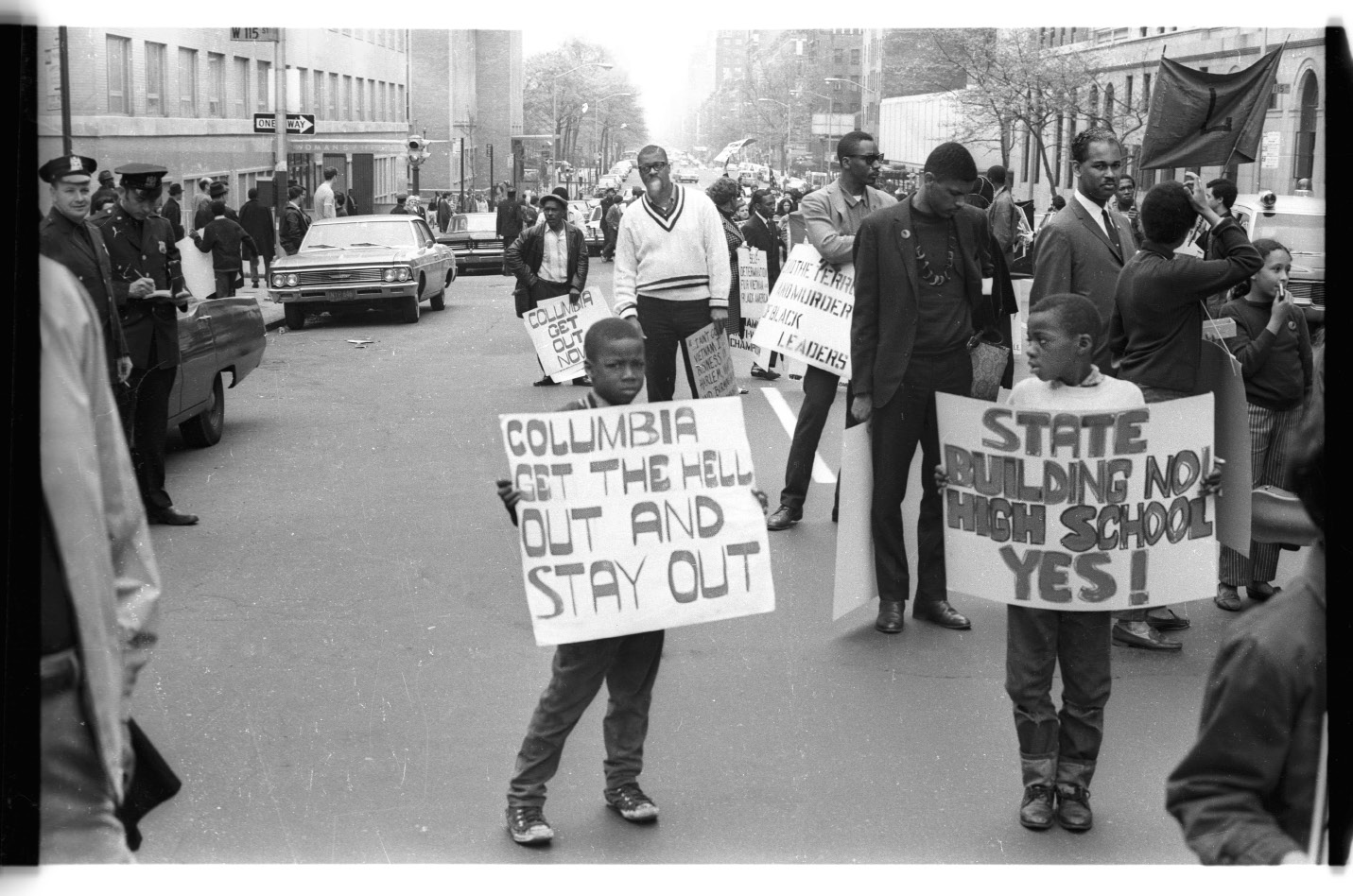

Like earlier black students at Barnard and Columbia, members of SAS were active in the community—organizing rent strikes, condemning police brutality, and joining civil rights demonstrations. In 1968, they turned their attention to Columbia, siding with Harlem neighbors in opposing Columbia’s decision to build a private gym in Harlem’s public Morningside Park, to which faculty and Columbia students would be welcomed through the front door and neighborhood residents admitted through the back.

Members of SDS cared about the gym, too. But since 1965, the Columbia chapter, along with its national organization, had focused on Vietnam and resistance to the draft, which, in 1968, stopped exempting male graduate students. For three years, SDS and others at Columbia had mounted teach-ins about the war, organized busloads of students for trips to anti-war demonstrations, protested ROTC drills on South Field, defied University rules by blocking access to military and CIA recruiters inside Columbia buildings, and condemned the University’s ties to the Institute for Defense Analyses, which conducted classified research for the Pentagon. Columbia officials responded not by opening dialogue, as the protesters wanted, but by placing them on disciplinary probation.

Sexual Protectionism

Between January 30 and April 4, a series of events triggered the student revolt. The Tet Offensive gave lie to American claims that the U.S. was winning in Vietnam. Mark Rudd, a Columbia junior, was elected chairman of its SDS chapter on a platform titled, “How to Get the SDS Moving Again and Screw the University All in One Fell Swoop.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. And an article about cohabitation, appearing in The New York Times, included an account of an unnamed Barnard student who, unbeknownst to College officials, was living off-campus with her boyfriend. Barnard’s dean of studies quickly identified the student as LeClair. The dean brought charges against her for lying on her housing form to Barnard’s judicial council, a committee of students, faculty, and administrators, with disciplinary authority over student conduct.

Defiant, LeClair questioned the College’s right to determine where she lived. She asked in the Barnard Bulletin, the College newspaper, “If women are able, intelligent people, why must we be supervised and curfewed?” Before the College’s judicial council, LeClair elaborated: “Although I am old enough by law to marry without my parent’s consent; support myself, which I am doing; live anywhere I want, without parental control; I am not old enough, according to Barnard, to live outside the dorm except as a domestic.” Obliged to enforce College rules but clearly on LeClair’s side, the council—including Barnard English instructor and pioneering feminist Kate Millett—ordered that LeClair be denied snack bar privileges and urged that the College policy be revised.

Press reports were soon picked up nationwide. Barnard’s new president, Martha Peterson, found herself deluged with demands that she expel Barnard’s wayward student. Fearing the effect on a new capital campaign, Peterson vetoed the council’s ruling and considered expelling LeClair. But over the weeks that followed, Barnard students, including a delegation that presented Peterson with a petition signed by half the student body, rose in LeClair’s defense. The group threated to stay until Peterson agreed to accept the council’s ruling and allowed LeClair to remain. Peterson relented.

Occupations

Unlike at Barnard, when Columbia students made demands, President Grayson Kirk often simply said, “no.” By April 23, the leaders of SDS and SAS, along with a number of supporters, determined to take drastic action. They proceeded to rally at Low Library to demand that President Kirk hear them out.

Blocked by other students, mostly athletes outraged by recent challenges to the University, two Barnard students, standing on a bench, shouted, “The gym!” At that, the protesters headed to Morningside Park to take down the fence that cordoned off the construction site and reclaim the land for Harlem. When the police arrived and started to make arrests, leaders diverted the remaining protesters to Hamilton Hall, which they occupied.

At first, the occupation had a carnivalesque quality. A student band played, attracting more students, Patrick among them. Columbia’s acting dean, Henry Coleman, entered and demanded access to his office; students allowed him to pass. Mao posters went up, and then balloons. Candy wrappers and other detritus began to litter the floor. As Patrick remembers, “For the black students, this was not an acceptable thing.” They came from “a long civil rights tradition, where our grandparents, and our grandparents’ grandparents said, ‘Every time you leave your house you represent the race. When you walk down the street, when you’re in a classroom, when you’re in public accommodations, you represent the race….You behave in a dignified fashion at all times.’ This was getting to be not such a dignified fashion.”

Moreover, the demonstrators’ goals began to diverge. SAS wanted the University to stop the gym’s construction; SDS wanted to stay in the building until Columbia severed its connection with the CIA and defense research. “Well,” Patrick worried, “we would have been in the buildings for two years.” At around midnight, SAS requested that SDS leave. “I remember being sad about it,” Patrick recalled, “because I was coming at a time when black and white together—‘We Shall Not Be Moved’—was the motto of the civil rights movement and what made it so effective…. But I knew that it had to happen. . . . We knew what we had to do to represent [the race], and that was to maintain [the cleanliness of] this building. We had to scrub the floors. We had to make sure that nothing is destroyed.” Before starting to clean, SAS released Dean Coleman.

Evicted from Hamilton, some fifty white protesters headed to Low Library, where they took over President Kirk’s suite. Over the next four days, other protesters occupied Avery, Fayerweather, and Mathematics Halls before settling in for a siege. Judging from later arrest records, about a third of the protesters were women, roughly half of them from Barnard. Ellen Feldman ’69 was “one of the first” to enter Low, “fervent” in her “opposition to the war, discrimination against African Americans, and the evils of capitalism.” Like everyone else, she waited in line to call her parents on the one phone in the office. Nancy Biberman ’69 also joined at Low, an experience she found “intense, intoxicating, and profoundly pre-feminist.” Like many of her Barnard friends, she cherished her relationships with the men in SDS, “at least in part because without them we could not have participated in [the] endless, informal, high-level meetings [that were] taking place. Yet, quietly, we resented being there on male sufferance, or if our consciousness had not yet clarified those amorphous feelings into resentment, we were at the very least confused.”

Most of the women were channeled into traditional gender roles: cook and office assistant. Cathy Tashiro ’68 organized all the cooking in the Mathematics building. Women did the same in the other buildings, but they harbored doubts. Biberman later saw a sign in Fayerweather she would “never forget.” It read: “To all women: You are in a liberated area. You are urged to reject the traditional role of housekeeper unless, of course, you feel this is the role that allows for creative expression. Speak up. Use your brains.” Inspired, Biberman wrote an article criticizing “male ego-trips” and declared women were trying to create a new form of leadership, “one that recognized us as women, yet also as political people with thoughts and actions which must be communicated.”

Occupied buildings were not the only places students gathered. Hundreds more rallied outside, observed by dozens of reporters and photographers. Some students came looking for their classes. When Beverly R. Johnson ’71 (later Basha Yonis) discovered that protestors had occupied the Mathematics building, where she was taking calculus, she was incredulous. “Why the Mathematics building? What kind of military-industrial grants can be going to a math department?” She admired the protesters. But she could not “imagine joining them in the occupation.” To her relief, she saw her professor had commandeered a portable blackboard and was teaching outside. She was “very proud of Professor Kolchin for honoring the occupation and still teaching.”

Others came to show their support. Constance Brown ’71 was one of the “step sitters and sympathizers,” as she describes herself. So was her classmate Mary Gordon ’71 (now Barnard’s Millicent C. McIntosh Professor in English and Writing), who grew up working-class. By day, Gordon “would go over to Columbia and chant and demonstrate—[I] never went into the buildings because I was on scholarship. I thought, ‘If I fall off this rung of the ladder, I’ll never be able to get up again.’” Alison Hayford ’68 took a place on the steps in front of Low Library, where she ventured to make “what must have been my first political speech.” She recalls “the tendency of males . . . to demonstrate a kind of eye-rolling tolerance when women spoke.”

Bonnie Fox Sirower ’70, initially “horrified” to see students occupy University buildings, within days “spent one night in Avery,” eating “oranges and peanut butter,” and talking “all night long about how we would make a difference.” The next morning, having second thoughts, she “sneaked out a window” to make her “feelings known another way.” She “coordinated a candle-light demonstration that started at Milbank and wound around all the Barnard blocks three times.”

Not everyone was sympathetic. The Columbia undergraduates who blocked access to Low on April 23 established a ring around the Library to show their opposition. They tried to prevent food from getting into the building. As sympathizers formed an outer ring around Low (and faculty inserted themselves as a buffer to prevent fights), sympathizers threw packages of food to occupiers standing in the windows, which the opposition did their best to intercept. That did not stop the flow of supplies. Damaris McGuire ’70 watched the successful execution of one delivery: “A middle-aged woman, carrying a large grocery bag, pushed her way through the various rings, shouting her son’s name. From one of the windows a boy popped his head out. ‘Yeah, Ma?’ She handed up the grocery bag, told him to be careful, and left.”

Police Violence

On April 29, seven days into the building takeovers, President Kirk called for New York City Tactical Police Force to clear the buildings. Police officers poured into the tunnels under the central campus and filled College Walk. They cut telephone and electrical lines and turned off water to the buildings. Early in the morning of April 30, they received the order to move in.

In Hamilton Hall, the first to be cleared, the arrests proceeded peacefully, in large part because the students had political officials on the outside negotiating on their behalf. These allies opened lines of communication between the students and police commissioner. Together, they agreed that if the University sent in the police, the students would not resist arrest but rather would walk out peacefully. Karla Spurlock-Evans ’71 later reflected that “the police that I saw were [all] black…. There was not a majority of black policemen in New York City at that time. So I think they had been identified and selected to come in to take this group of black students.”

In other buildings, the story was different. There were no advance negotiations, no agreements about resisting arrest. Some did walk out. Others locked arms in peaceful resistance. And a few fought back. The police, all white this time, broke down doors and made their way through the furniture barricades. Perhaps resentful of the students for the privileges the officers never had, they used their flashlights and night sticks liberally.

Then, to everyone’s shock, the police turned on the crowd of spectators. Some in the crowd were supporters; others hoped to prevent violence against the occupiers; many had come out of simple curiosity about what had been advertised across campus as a peace demonstration. The police attacked them all. Hayford, on the steps of Fayerweather Hall, remembers “being thrown over a hedge and seeing students with blood streaming down their faces.” Susan Krupnick Fischer ’68 stood outside the buildings hoping to “protect the protestors from the police. How innocent and naïve we were,” she recalls. “The police came, saw us, clubbed and threw us around, arrested those who weren’t fast enough to run away.”

The worst were the mounted police, swinging their nightsticks. “Some even went into the [Columbia] dorms where students were minding their own business and started hitting people on the head with clubs,” recalls Sirower. The mounted police did not stop with clearing the Columbia campus. They chased fleeing students out to Broadway and down 116th Street, clubbing them as they went. “It was truly horrifying to see,” says Joy Horner Greenberg ’71, one of many who watched from Barnard residence-hall windows.

The police “riot,” as The Washington Post called the attack, had a dramatic effect. A protest that had initially attracted only a small minority of the University population now won the support of thousands of students and faculty who condemned the University for excessive force and failure to listen to students’ grievances. The Grateful Dead gave an impromptu concert in support. Students threw up picket lines around classroom buildings. Some professors moved their classes to their apartments or held them on the lawns outside buildings. It was, as Elizabeth Langer ’68 observed, a “transformative moment.”

Other classes continued as before, however, and many Barnard students, even those sympathetic to the protesters, objected to the picket lines that blocked them from attending. Some feared losing their scholarships if they did not finish their coursework. Grace Druan Rosman ’68, who felt that the uprising diminished her Barnard experience, remembered having “a lab experiment in progress for my senior project” that she was unable to complete. “Fortunately, I was able to convince the protesters to let me in and turn it off to prevent the chemicals from overflowing! I was also unable to complete my Mishnah course and got a pass rather than being able to submit my final paper. Luckily, Barnard carried on and I could take my biology comprehensives as well as complete my student teaching.”

Later that spring, there were two more occupations and two more mass arrests. Langer was among those locked up. She worried that jail meant the end to her dream of becoming a lawyer, but nevertheless felt proud that “I had taken a stand and crossed a line.”

For the most part, Barnard students felt luckier than their Columbia peers in having their own separate community. They were able to create the feeling of a “safe haven” away from the violence on the other side of Broadway, as well as an alternative to the sense among Columbia students that administrators and even many faculty were distant, rigid figures to whom students could not talk.

What Changed

Although the war in Vietnam continued for seven more years, the protesters were, in many ways, successful. They persuaded Columbia to put an end to classified war research, cancel construction of the Morningside Park gym, ask ROTC to leave, and stop military and CIA recruitment. Barnard, for its part, entered a new era. When, in the fall of 1968, SAS leaders began talking about the need for political assassinations, Barnard’s black students left to form their own organization, the Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters. BOSS enabled black women to focus on the issues that mattered most to them and to speak without being drowned out by SAS’s men. Feminism was not at first an issue for them. As one black student asked, “How can I fight for white women to get jobs that black men still can’t get?” They wanted more black women on campus and the chance to read about blacks in their courses. Increasingly alienated from campus life, they demanded the right to live on an all-black floor in the dorm.

Black students were not the only ones feeling alienated in 1968. Rather than agree to the condition that President Peterson imposed—that she abide by College rules—Linda LeClair dropped out. Others left, too, estranged from academic life. Many recalled the late sixties as a lost time, a time of chaos.

For others, however, being at Barnard in 1968 meant “freedom,” “feeling intensely,” and the chance to embark on lives that had been impossible for their mothers. Feminism took hold on the campus. Within a year, Barnard allowed students to live where they wished. Women from Barnard joined the campaign to end New York’s ban on abortions, which finally became legal in the state in 1970, three years before Roe v. Wade. Some students like Barbara Bernstein ’71, “after four years of looking for the right man,” came to realize “I was looking in the wrong direction,” and embraced a lesbian identity. More courses on women, and later gender, began to appear in the course catalogue.

Many Barnard graduates went on to pursue careers in law, economics, and science. Many devoted themselves to social activism. Peggy Farley ’69 helped start New York State’s Higher Education Opportunity Program, which supports disadvantaged college students, and dedicated her life “to global egalitarianism.” Perry-Lynn Moffitt ’68 became a draft counselor and reports that she “never lost a client to the Army.” Ruth Stuart Bell, despite having been opposed to the protests, left Barnard with a broader sense of life’s possibilities, and with greater empathy for those less fortunate. She married, moved to Midland, Texas, and remained a conservative Republican. But she also became president of Planned Parenthood in Midland and helped found a shelter for battered women there. Many others were also deeply affected, perhaps no one more than Carol Santaniello Spencer ’71. She grew up on Long Island, “only fifteen miles but many worlds away” from Barnard. When her father, upon learning of the demonstrations, demanded that she return home, she announced that she wanted to live in the city. “You will leave this house either in a bridal gown or a casket,” he declared.

She left, wearing blue jeans instead. •