The Oscar-nominated actress says science informs her art and vice versa

“What is AI, really?” asked a colleague in a recent group discussion.

The answers among us were varied: some more tech-focused, others broader and far-reaching. After parsing a variety of definitions, the group conceded that artificial intelligence means different things to different people. A chemist might see AI one way, while an artist might see it another way. Likewise, faculty, students, and staff hold different views depending on their department or discipline.

AI isn’t coming; it’s here. And while not everyone on campus is using the technology, conversations grappling with the meaning and challenges of AI are being held in offices, classrooms, labs, and studios. Barnard’s faculty, staff, and students are delving deep on task forces, through research, and in publications — often breaking ground and leading other institutions of higher ed to take notice.

“We’re going to have to think about how artificial intelligence [and] the speed of innovation affects our curriculum, our teaching methods, but also how all of us do our work,” said President Laura Rosenbury in a recent town hall.

While there’s much to learn and understand about this formidable technology, the Barnard community has been quick not only to engage with it but to innovate.

In the past year, the storm clouds of ChatGPT converged nationwide as students began using the readily available technology to write essays and research papers. At the time, few higher education institutions had any real policies in place. Barnard, however, was ahead of the curve.

On campus, the conversation around AI had reached a crescendo by the late fall of 2022, says Melissa Wright, the executive director of the Center for Engaged Pedagogy, as faculty grading papers started to suspect that students were drawing on the technology. Professors began knocking on Wright’s door looking for guidance. Wright and her team got to work. By mid-January 2023, the Center had published recommendations on the College website under the heading “Generative AI and the College Classroom” — making Barnard one of the first institutions of higher ed to do so.

We’re going to have to think about how artificial intelligence [and] the speed of innovation affects our curriculum, our teaching methods, but also how all of us do our work.

Wright says they weren’t operating in a silo on campus. Not long after the guidelines were published, a group made up of staff and faculty formed the AI Operations Group, which meets weekly to discuss the ever-changing AI landscape. In addition to Wright, the cohort includes Melanie Hibbert, director of Instructional Media and Technology Services (IMATS) and Sloate Media Center; Alexander Cooley, vice provost for research, academic centers and libraries; Victoria Swann, executive director of IT; and Monica McCormick, dean of Barnard Library and Academic Information Services (BLAIS).

Cooley says that given the ever-amorphous conversation happening around AI, it would be surprising if any college would have a set of guidelines on how to proceed — yet, arguably, this is where Barnard is leading.

“We were one of the first schools to come out with suggested AI guidance for instructors, and what we didn’t want to do was force the faculty to have a particular stance about AI,” says Cooley. “We don’t want to ever be in a position of mandating to colleagues on how they teach or how they engage.”

If one is to engage, then it should be done competently, carefully, with transparency and training, says Melanie Hibbert, who recently published a paper, “A Framework for AI Literacy,” in the higher-ed tech journal Educause. Hibbert and her co-authors, Wright and IMATS colleagues Elana Altman and Tristan Shippen, prioritize the framework in four levels: Understand AI, Use & Apply AI, Analyze & Evaluate AI, and Create AI.

According to the paper, understanding involves basic terms and concepts around AI, such as machine learning, large language models (LLMs), and neural networks. When using the technology, one should be able employ the tools toward desired responses. “This has been a particular focus at Barnard, including hands-on labs, or real-time, collaborative prompt engineering to demonstrate how to use these tools,” the authors say. When analyzing and evaluating the work, users should pay attention to “outcomes, biases, ethics, and other topics beyond the prompt window.” The authors note that while Barnard has provided workshops at the Computational Science Center for users to begin creating with AI, this is an area that’s still evolving.

As quickly as AI has evolved, so have the potential problems, such as bias. Here, too, Barnard moved quickly. The College disabled AI detection software after it was shown to exhibit biases against non-native English. Using a metric called “perplexity,” the software measured the levels of sophistication in writing that favored lifelong English speakers. Computer science professor Emily Black has been researching fairness in AI to ensure that decisions made using AI algorithms treat people fairly and equitably.

Cooley says that users should always be aware of where large language models and visual images are taken from. For example, Wright notes that many images and texts draw from the public domain databases populated with male painters, male photographers, and male writers.

“We are a feminist College, and we are letting you know that there’s a century of male-dominated scholarship and textual repositories that take away our voices,” she says.

Victoria Swann said her primary ethical concern centers on the commercialization of the science.

“The danger is not, you know, the Terminator is coming for your children, the danger is what the get-rich-quick venture capitalists are going to do to hollow it out,” she says, adding that she’s also concerned about the tremendous amount of natural resources being used to power AI. As an example, she cited Microsoft’s massive expansion in Iowa, the farming state that’s now home to the company’s epicenter of AI. In September, Axios Des Moines reported that the company consumed 11.5 million gallons of water a month for cooling, or about 6% of the area’s total usage during peak summer during the past two years.

Rebecca Wright, director the Computer Science Program of the Vagelos Computational Science Center, says other causes for concern include privacy, misinformation, and disinformation, to say nothing of apprehensions about the future of work and human creativity.

“We must educate our students and our community to understand AI and use it safely,” she says. “Through the research of our faculty in Computer Science, we are contributing to the development of safe and fair AI tools and techniques, as well as critical applications of AI that advance society.”

In separate interviews, nearly every member of the operations group warned users at Barnard to be cautious of what they feed AI, to make sure they aren’t uploading sensitive, private, or proprietary data, a major concern with original research and copyrighted materials.

As with their approach in the classrooms, whether and how professors use AI in their research remains up to them. But some faculty members have already embraced the technology. Kate Turetsky, director of the Group Dynamics Lab, is part of a team exploring how to use it for qualitative coding. Not surprisingly, the computer science professors are taking a deep dive into both foundations and applications of AI, including Smaranda Muresan’s work in natural language processing, Corey Toler-Franklin’s focus on computer graphics and vision, Brian Plancher’s research on robotics, and Mark Santolucito’s work in program synthesis.

My overarching thought is that this issue — what I understand to be a major change in computing — challenges us to find ways to bring the entire community along on a learning journey.

Though AI has garnered a lot of attention, Hibbert says that two recent surveys of 318 Barnard students and 52 faculty found that over a fourth of the students and over half the faculty had yet to use the technology. While the student data was largely representative of the overall student population, the faculty data was less so. Nevertheless, the results still surprised Hibbert.

“You have to take some of this with a grain of salt,” says Hibbert. “But still, that really shocked me in a way. I just hope people don’t fear it.”

Monica McCormick provided a positive spin.

“My overarching thought is that this issue — what I understand to be a major change in computing — challenges us to find ways to bring the entire community along on a learning journey,” she says.

For her part, President Rosenbury holds a pragmatic long view.

“We’re going to have to start experimenting with possibilities,” she says. “It’s going to take a lot of trial and error.” But ultimately, as she told the audience at Inauguration, “we aren’t just going to lean in on these issues. We’re going to lead into these opportunities.”

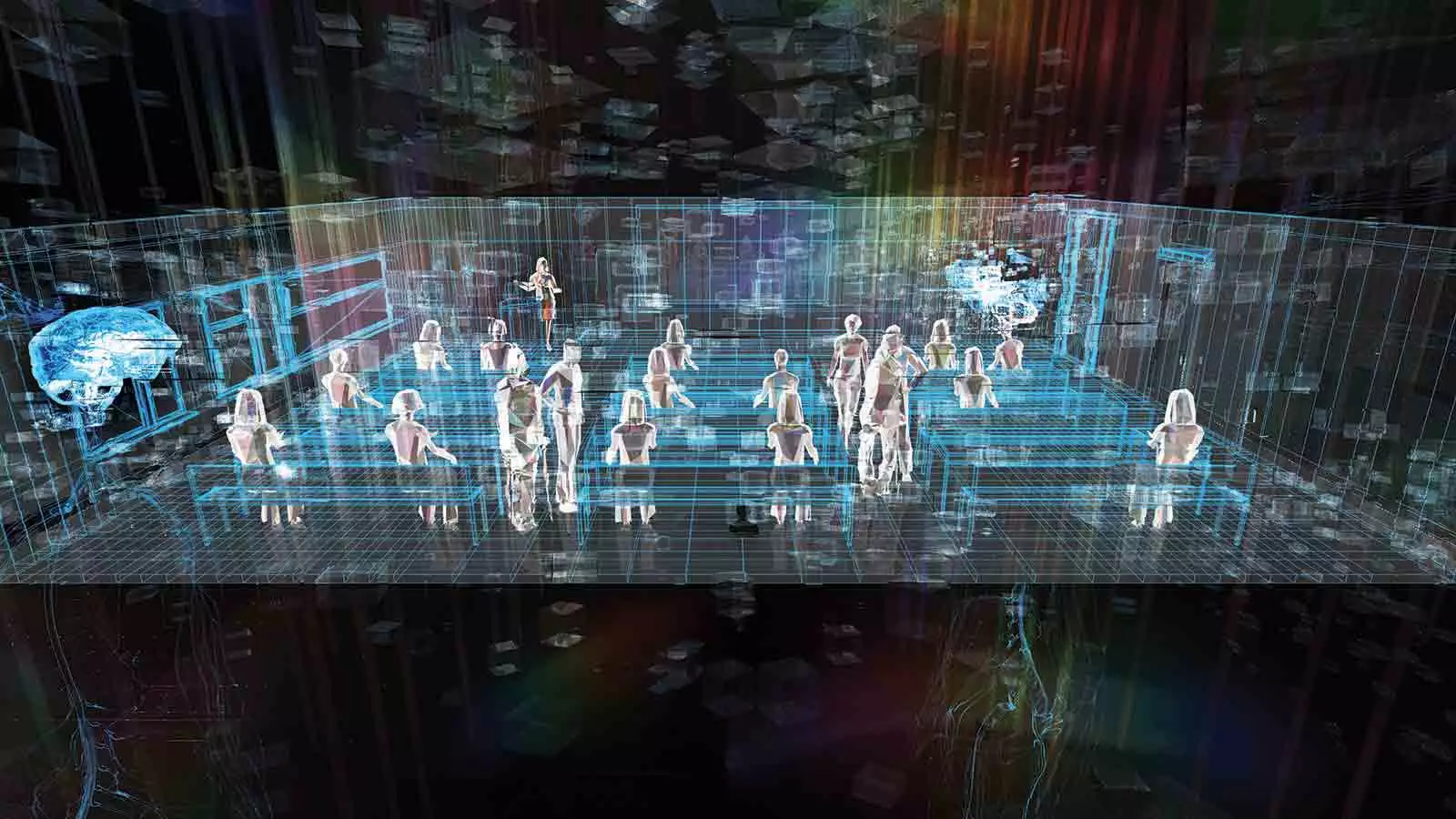

Illustration by Violet Frances