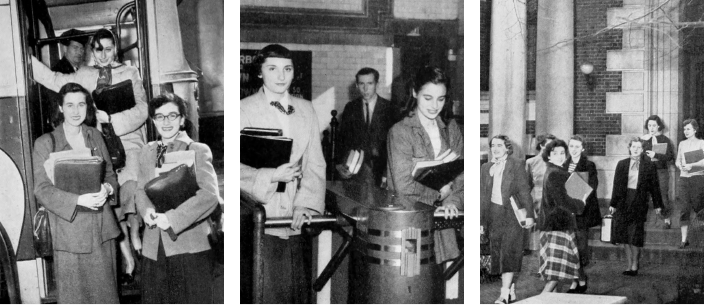

Despite Virginia Gildersleeve’s efforts to nationalize the Barnard student body during her deanship (1911-1946), it retained a local character. In 1947, there were just under 1,200 women, more than half of whom were New York City residents. Another quarter came from within a 30-mile radius of Morningside Heights. Two out of every three of these students commuted—many because the $700 tuition represented a strain on family finances, while the additional $650 fee for room and board was prohibitive. Many New Yorkers managed Barnard’s tuition in the 1950s only with the help of a Regents scholarship, which effectively cut the cost in half.

More than 70 percent of Barnard students in the post-war decade were public school graduates, half from New York City. Many of these applicants first heard of Barnard through a teacher, herself often a Barnard alumna. Despite Gildersleeve’s efforts and those of the inter-war trustees, Barnard continued to attract few graduates from the private girls’ schools clustered on the city’s East Side—Brearley, Spence, Nightingale— or the nationally known boarding schools.

Dean Gildersleeve’s successor, Millicent McIntosh, understood the economic constraints her students faced. In 1949, she advised the trustees to keep the tuition as low as possible. It is not a coincidence that the first substantial gift she solicited as dean, from Eugene and Agnes Meyer in 1948 for $50,000, was for a Barnard Hall social space for commuting students.

Many students in the early 1950s were the children of immigrants, with most the first woman in their family to attend college. While most of the Jewish students in the Gildersleeve era were from prosperous German-Jewish families residing on Manhattan’s East Side, in the post-war years they were more likely one generation removed from Russia and Eastern Europe and were children of the outer boroughs. Barnard in the post-war decade attracted fewer legacies than other sister colleges—and appeared none the worse for doing so. “I am not so interested in whether her mother went here or not,” Helen McCann ’40, director of admissions from 1952 to 1977, told her fellow alumnae in 1953. “I am interested in the daughter.”

Thus, Dean McIntosh in 1947 found herself taking over a college whose student body was markedly different in social composition and family wealth from that of Bryn Mawr, where for eight years she had been a student and teacher, and from Brearley, which she had led for 15 years. Her response was not, as Gildersleeve’s had been back in 1911, to set out to make Barnard more like Bryn Mawr, but to applaud its heterogeneity. “We are blessed,” she declared in her inauguration, “with a student body as varied and as interesting as New York itself.” She realized that what distinguished Barnard from more socially elite schools was an institutional strength. It was Mrs. Mac’s embrace of Barnard’s urban character that set the College on a path to Queens-reared President Judith Shapiro’s pronouncement in 1995: “I’m a New Yorker. You got a problem?” •