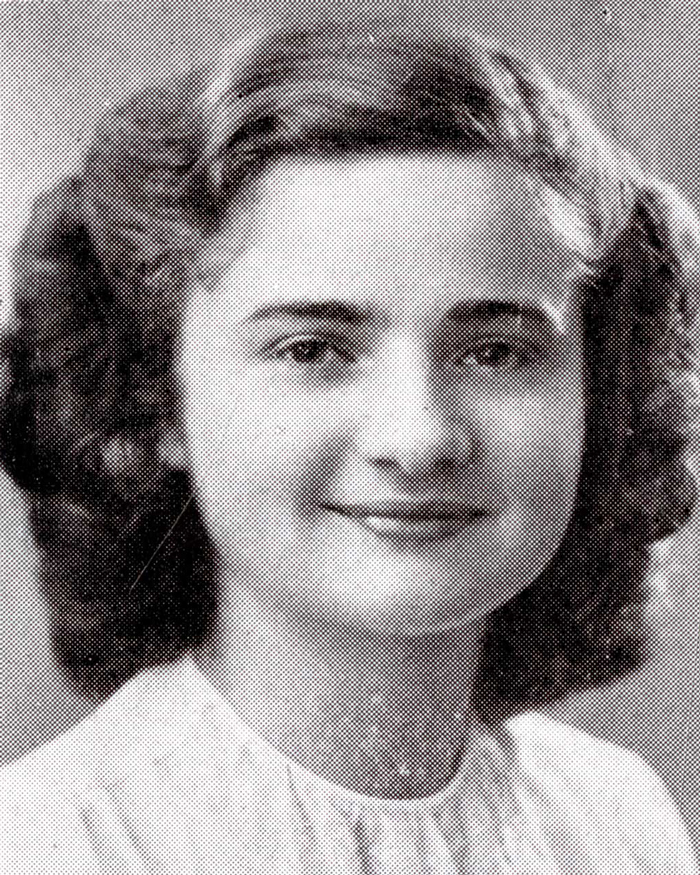

Around 75 years ago, two members of the Class of ’49 became friends.

Their connection seemed almost inevitable: Both were fluent German speakers and philosophy majors, and they shared passions for writing, music, opera, and theatre. But it was also improbable: Marlies Wolf Plotnik and her family were refugees who had suffered years of persecution in Germany, and Marion Hausner Pauck’s father was upset that his daughter had befriended a Jewish girl.

Yet the classmates’ bond remained fast, even when they lived on opposite coasts and went years without seeing each other. “It never let up,” Plotnik, 93, says. “The fact that we were never not in touch is unusual. ... I had other connections, but nothing as solid as Marion.” Not surprisingly, Pauck, 93, agrees. “We’ve always been harmonious,” she says, “and that doesn’t happen often.”

Plotnik had lived in New York for just six years before being accepted to Barnard. She and her two older siblings were born in Darmstadt, Germany, where her father was a respected lawyer and her grandfather owned a successful factory. The family traced its history in Germany to 1560 and had felt secure in their homeland.

As the Nazis and Hitler rose to power during Plotnik’s childhood, anti-Jewish sentiment festered and spread. Her 75-year-old grandfather suffered a fatal heart attack the day he was forced to purchase a large sign proclaiming “He who deals with Jews is a traitor” and display it at his factory. Plotnik’s parents waited three anxious years for visas that allowed them to join New York cousins in 1939.

“I always had the fear it could all be taken away from me,” Plotnik said in a 2010 oral history interview conducted for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. “This has haunted me.”

Pauck, the sheltered only child of German immigrants, had a very different upbringing. Raised in New York City, she savored Sunday services at Holy Trinity Lutheran Church on the Upper West Side. The airy Gothic Revival building, illuminated by jewel-hued stained-glass windows, was the most beautiful building she’d ever seen, and it reverberated with stirring sermons. “And I loved the peace and quiet of it,” Pauck recalls. Barnard didn’t offer religion as a major, but philosophy, taught by respected department chair Gertrude Rich, was a popular alternative.

Pauck and Plotnik met in a philosophy class and then founded and wrote for Focus, Barnard’s literary magazine. Together, the young women interviewed the actress who’d received a Tony nomination for her portrayal of Blanche DuBois in the 1947 Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire. “I thought we had some nerve ringing the doorbell of Jessica Tandy, but we did,” Pauck says. “She was so gracious! She said, ‘Please come in.’”

Devotees of Wagner and Mozart, the two women attended the symphony together and frequented the Metropolitan Opera. “We were both in love with Ezio Pinza,” Plotnik says of the Italian singer. She recalls regularly seeing Columbia president Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wife, Mamie, on campus; the women’s diplomas bear Eisenhower’s signature.

The classmates’ connection flourished despite the disapproval of Pauck’s father. “But he had made a big mistake,” Plotnik says with a chuckle, “because he sent her to a Friends [high] school that gave her a liberal education.” Pauck notes that her father’s views were at odds with his behavior: He gave food to German-Jewish refugee families and helped them find work. Nonetheless, she says, he harbored some prejudices. “He and I had big fights,” she recalls.

After graduating from Barnard, Pauck studied at Union Theological Seminary and earned a Master of Arts degree in 1951 from Columbia. Although she had no plans to seek ordination, a male classmate told her he did not approve of women even attending divinity school. “You’ll take all our jobs,” he said. She couldn’t help laughing “because the male ego was far more fragile than the female.”

Pauck edited religious books for Oxford University Press and studied with German-American theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. She and her husband, Wilhelm Pauck, wrote a 1976 biography of Tillich that she notes proudly is still in print. Her husband, a professor, taught at Vanderbilt, the University of Chicago, and finally at Stanford.

After his death, in 1981, Marion Pauck remained in the San Francisco area, where she is working on a memoir and still attends church services. “My inner life is certainly religiously bound,” she says, explaining that she views religion as “a way of life, a way of thinking that is with you all the time.”

Plotnik married Eugene Plotnik (Columbia ’50),

who became an editor, PR executive, and creative director. Marlies Plotnik launched and ran a New York City agency that matched advertising copywriters with clients such as IBM and major banks. She was especially pleased that her earnings put the couple’s two sons through college. Eugene Plotnik died in 2008.

Plotnik and Pauck’s connection has bridged two centuries. During the five years that Plotnik served as president of the Class of ’49, Pauck was her vice president. When Pauck finished a book she enjoyed, she wrapped it up and mailed it to Plotnik. Pauck sometimes stayed with Plotnik when she visited New York.

The former classmates over the years developed a habit of beginning each letter — and then each email — with “Geliebte Freundin” (“beloved friend”). Initially, Plotnik says, “we did this as a nostalgia trip,” but the greeting stuck, and they continue to faithfully use it. “That phrase,” she notes, “is always followed by an exclamation point.”