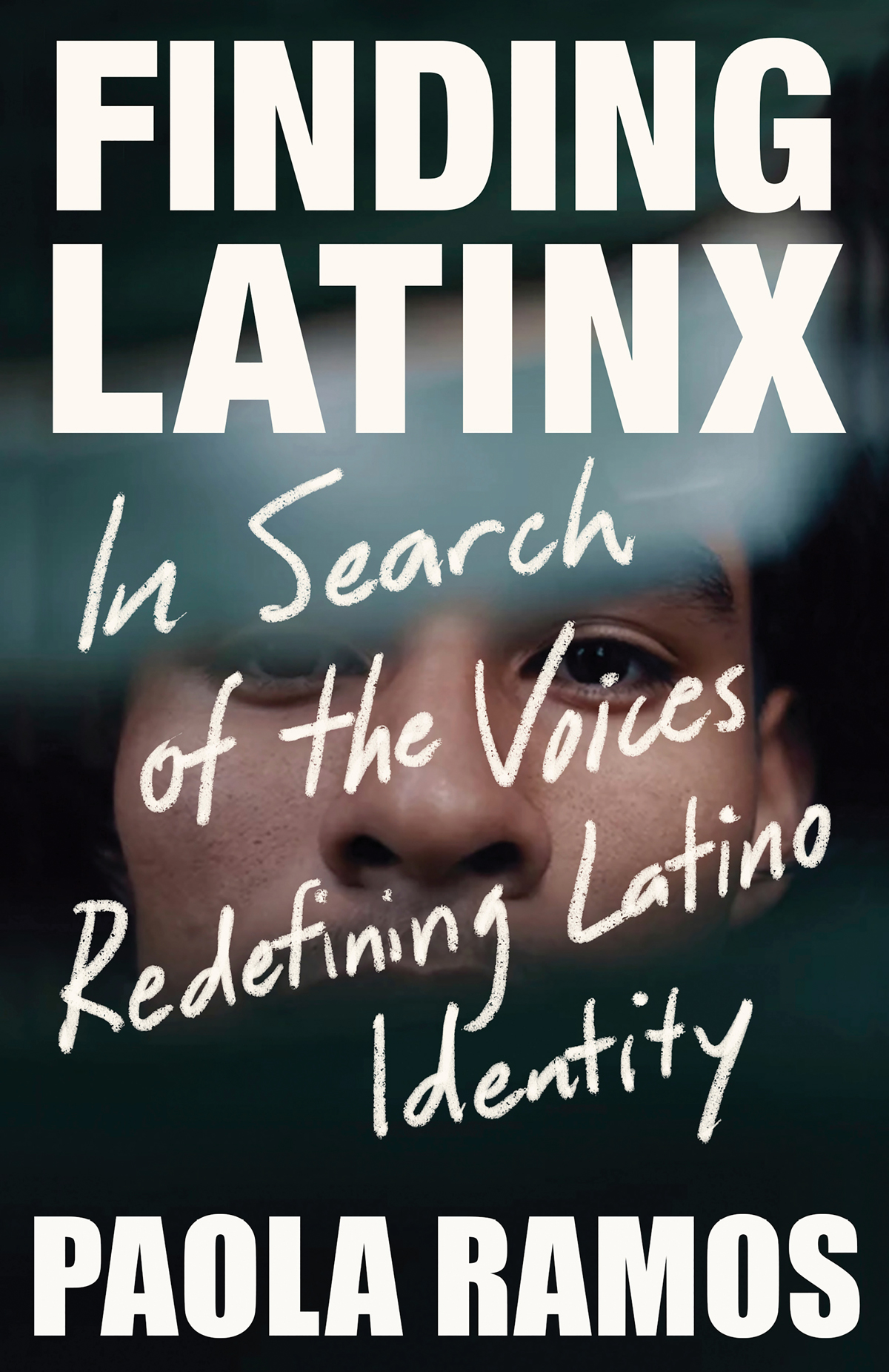

In the wake of the 2016 U.S. presidential election, journalist Paola Ramos ’09 set out on a cross-country quest to try to understand what binds and defines the Latin American community — and her own place in it. Ramos, who grew up between Madrid and Miami and is now a correspondent for VICE News, MSNBC, and Telemundo, traveled to all corners of the nation to hear from overlooked Latino voices, from California’s lush Central Valley to the Walmart in El Paso, Texas, where 23 people were killed in 2019. Ramos distilled her observations in her illuminating new book, Finding Latinx: In Search of the Voices Redefining Latino Identity, which was released just two weeks before Election Day 2020. For Ramos, who is queer, the word “Latinx,” a gender-neutral term for people of Latin American heritage, got to the heart of her pursuit — “It captured the stories of all these people under one umbrella, spanning so many separate identities,” she writes. We caught up with Ramos, who had just returned to Brooklyn after many months on the road.

How did your background influence your decision to become a journalist?

My parents are both journalists and immigrants [Paola’s father is Jorge Ramos, a Mexican American news anchor and journalist; her mother is Gina Montaner ’87, a Miami TV station managing editor and syndicated columnist and the daughter of exiled Cuban author Carlos Alberto Montaner]. The narrative growing up involved discussions about the Castro regime or Mexico, and why my dad decided to leave Mexico, which was because of censorship. The core of my upbringing was watching them write, watching them on screen, reading them in newspapers. I chose a string of that, which was politics. When I was at Barnard, I was a political science major. [Through my work] I’ve been able to observe and understand where the balance of power is — sometimes that’s been through politics and sometimes that’s been through journalism. I’ve had the privilege to go back and forth between both.

What was the impetus for writing this book?

It was almost exactly four years ago, when I was working in Hilary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. My fancy title was Deputy Director of Hispanic Media. For almost two years, I was convinced that on Election Day, in the face of someone like Donald Trump, Latin Americans would show up in overwhelming numbers. Turns out that less than 50% of eligible Latino voters showed up. As a campaign and as a country, we didn’t understand who they were. I was also trying to understand who we were. And then when the word “Latinx” popped up — and it was increasingly among us in 2016 — it, to me, was very telling of a community that was more diverse and changing than I realized.

What was most surprising to you, as you traveled the country and reported for this book?

Going into places that I thought I knew and discovering things I didn’t know. Even in New York City, there’s a big and powerful community of Latino Muslims. Never once had I read about it or come face-to-face with it. Also, going into places like the Midwest that I thought were going to feel cold and foreign and abstract [and instead] were more beautiful than I expected. But going back [home] to Miami, which is at the center of politics — everyone is trying to figure out what happened in Florida [in the November 2020 election] — was the culmination of everything for me. I felt that a lot throughout the process.

You essentially went on a listening tour to write this book. It strikes me that when politicians talk about listening to their constituents, this is the epitome of what they should be doing.

The book is 1% of the picture, and I hope it encourages politicians, particularly Democrats, to go back to these battleground states and put away biases and dig into this community. It takes listening and wide eyes to see things we haven’t seen before. There are Black Latinos, there are women who are fighting for abortion rights — it’s an extremely complex and nuanced community.

Throughout all of these stories, there is this ache to feel like you belong in this country. I hope that [this feeling] also translates into real power, that [Latinx people] end up running for office, voting, or getting the job they want or being in leadership positions. We can talk about this in a thousand ways — so long as these are just stories, they don’t translate into power. But I do think we’re heading that way.

What role has Barnard played in your life?

Barnard gave me a lot of confidence that I didn’t have. I moved back to the U.S. from Spain when I was going into my junior year of high school. Barnard had a lot to do with my ability to write this book. I became comfortable in my skin and who I was. Being gay and being Latina and having diverse friends became normal, and I became proud on campus. They’re still my best friends to this day. Being in political science seminars, writing my thesis, and getting the basics of politics is where it started for me.