When author and therapist Mary Pipher published her seminal book Reviving Ophelia in 1994, she underscored the contradictory, confusing, and damaging messages directed at adolescent girls.

“Girls struggle with mixed messages: Be beautiful, but beauty is only skin deep. Be sexy, but not sexual. Be honest, but don’t hurt anyone’s feelings. Be independent, but be nice. Be smart, but not so smart you threaten boys,” she wrote in her New York Times bestseller. Pipher and others pointed to mainstream media for helping to reinforce this confusing, impossible set of teen girl standards.

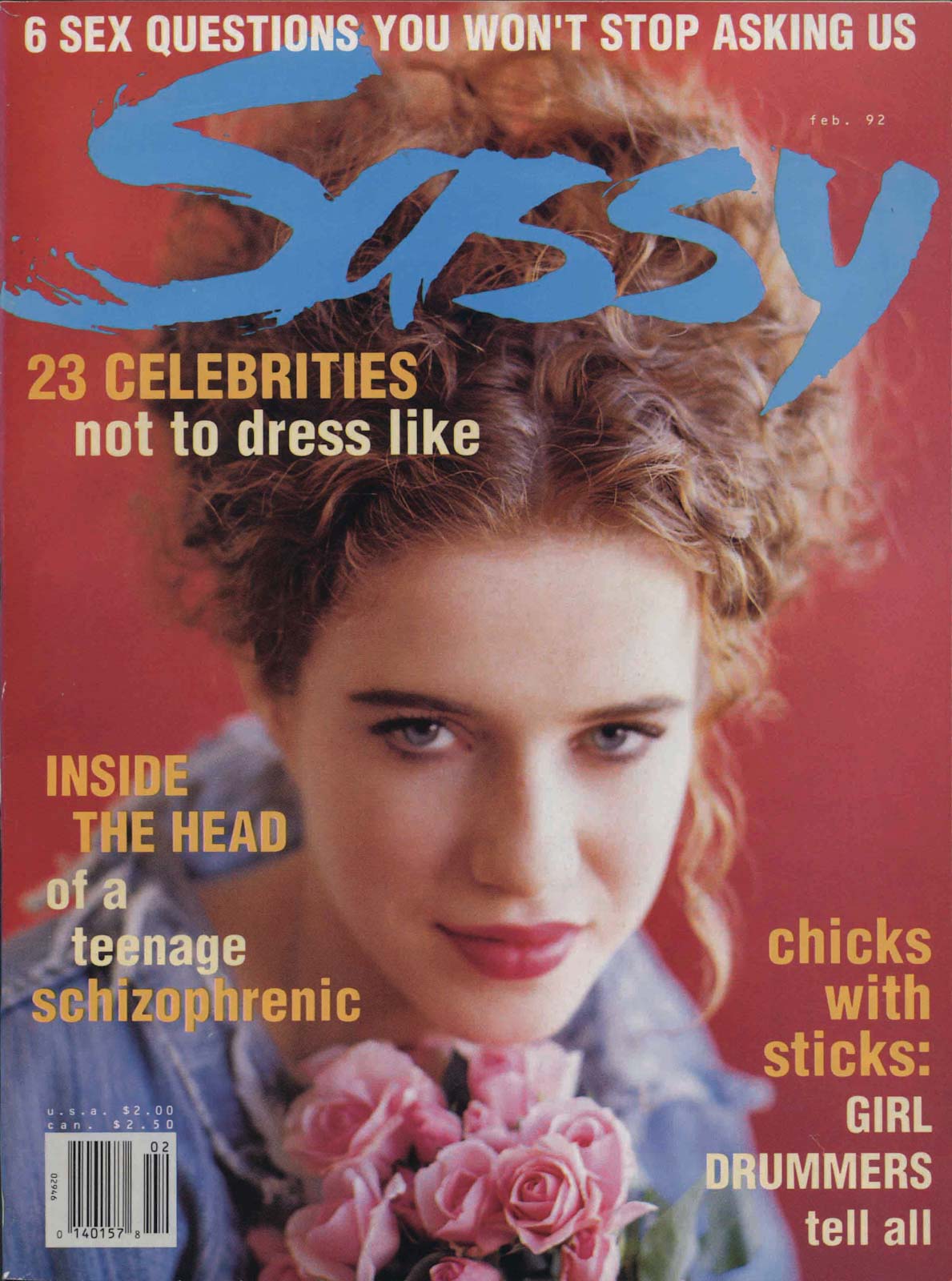

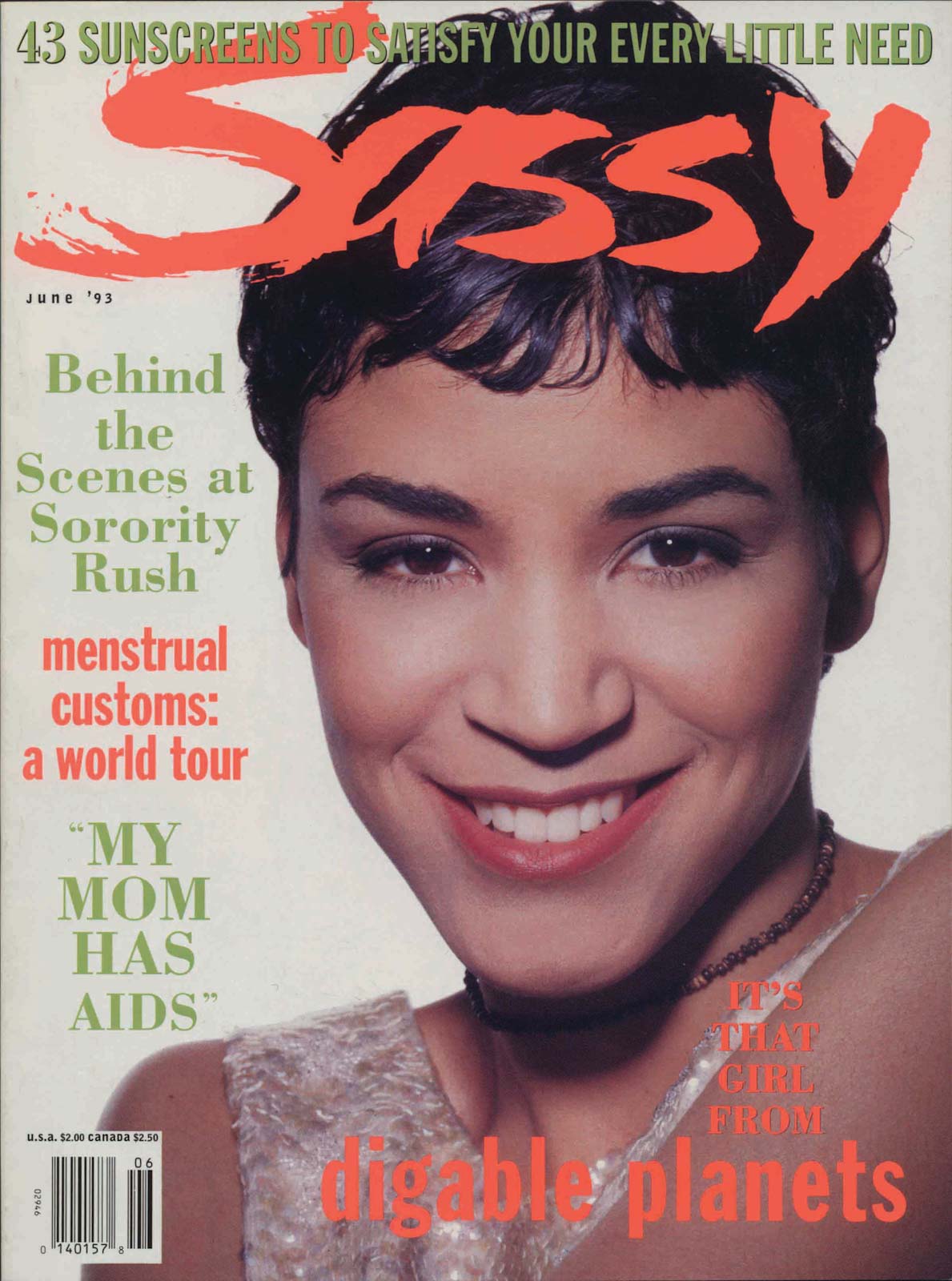

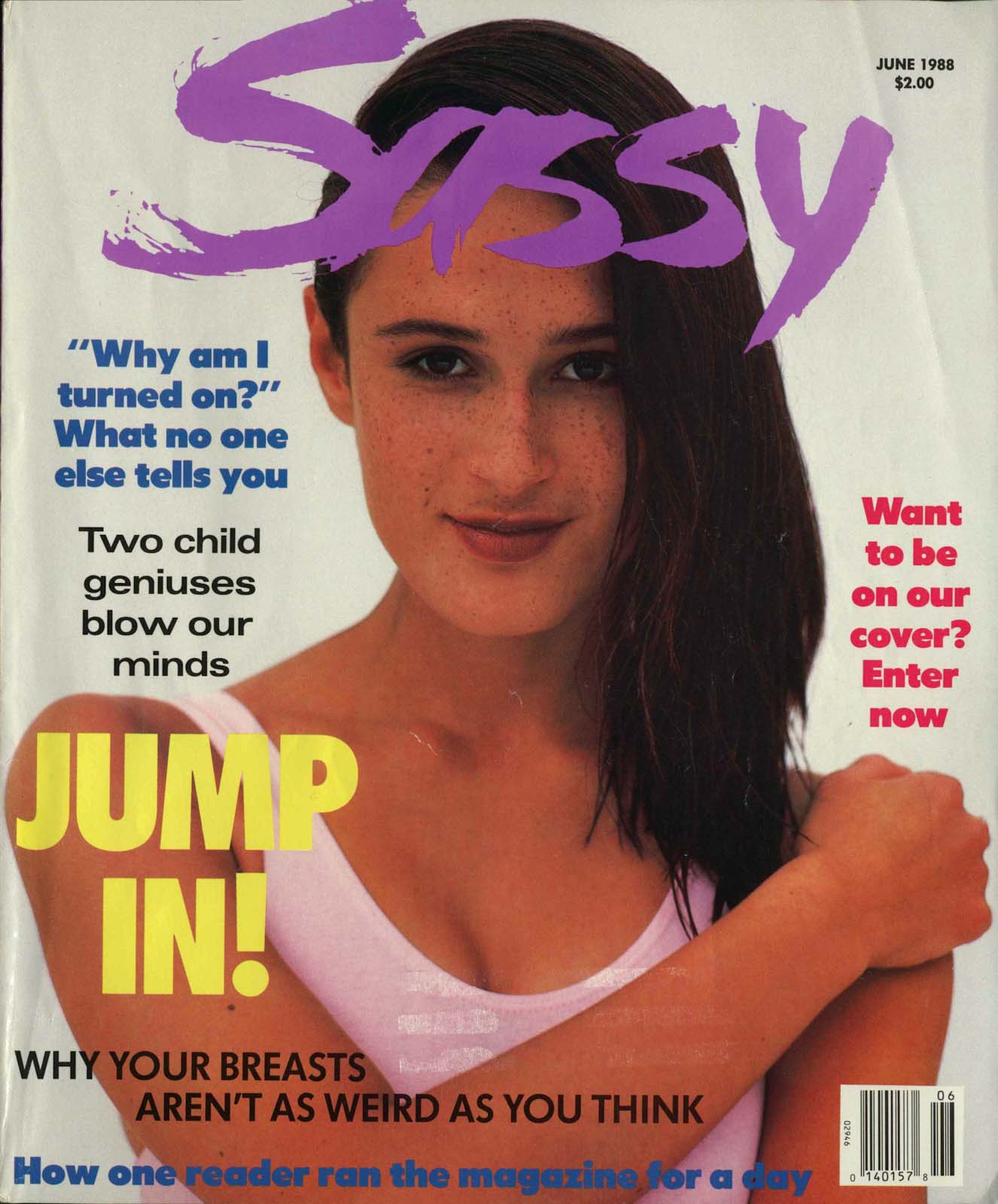

Enter Sassy, the magazine that offered a very different message, a counterpoint to the teen girl magazine model of the time. For a number of women who came of age during the late 1980s and early ’90s, Sassy holds a unique place in their hearts. The edgy teen glossy, helmed by founding editor Jane Pratt, was an oasis of real-girl feminist power and celebration in a sea of magazines that featured the prevailing themes of the day — namely, how to be thinner, prettier, smarter, and more appealing to boys.

“Sassy was a refuge from airhead teenybopper magazines, and in its first two years, the magazine established its worldview,” wrote Kara Jesella and Marisa Meltzer in their 2007 book, How Sassy Changed My Life. “Girls weren’t encouraged to be smart for the sake of getting good grades or getting into a good college. Instead, they were encouraged to be themselves.”

From its beginnings, it was clear that Sassy was a different kind of teen publication, making its mark with articles such as “So You Think You’re Ready for Sex? Read This First”; “Backstage at Miss America,” an exposé on the dehumanizing aspects of the pageant; and “Life After Suicide,” which covered the deaths of three teens and how it devastated their families. When the magazine folded in 1996, after an eight-year run, it left a gaping hole.

Now the full, 80-issue collection of Sassy has a home at Barnard. Jenna Freedman, director of the Barnard Zine Library, working in her capacity as the personal librarian for the College’s Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, spent six years trolling eBay and Twitter to collect the entire run. Freedman says she set out on this quest partly because she received a number of inquiries over the years. While researching their book, Jesella and Meltzer had even cross-referenced Sassy’s listings of zine recommendations, and that led them to Barnard’s robust zine library.

“Sassy had a zine-of-the-month feature, so [some of our] zines are widely ordered and read because they appeared in Sassy,” says Freedman. “It seemed the magazine had a special relationship with our zine library. I guess I was thinking with both brains, as director of the zine library and gender and sexuality studies [when I decided to acquire Sassy].”

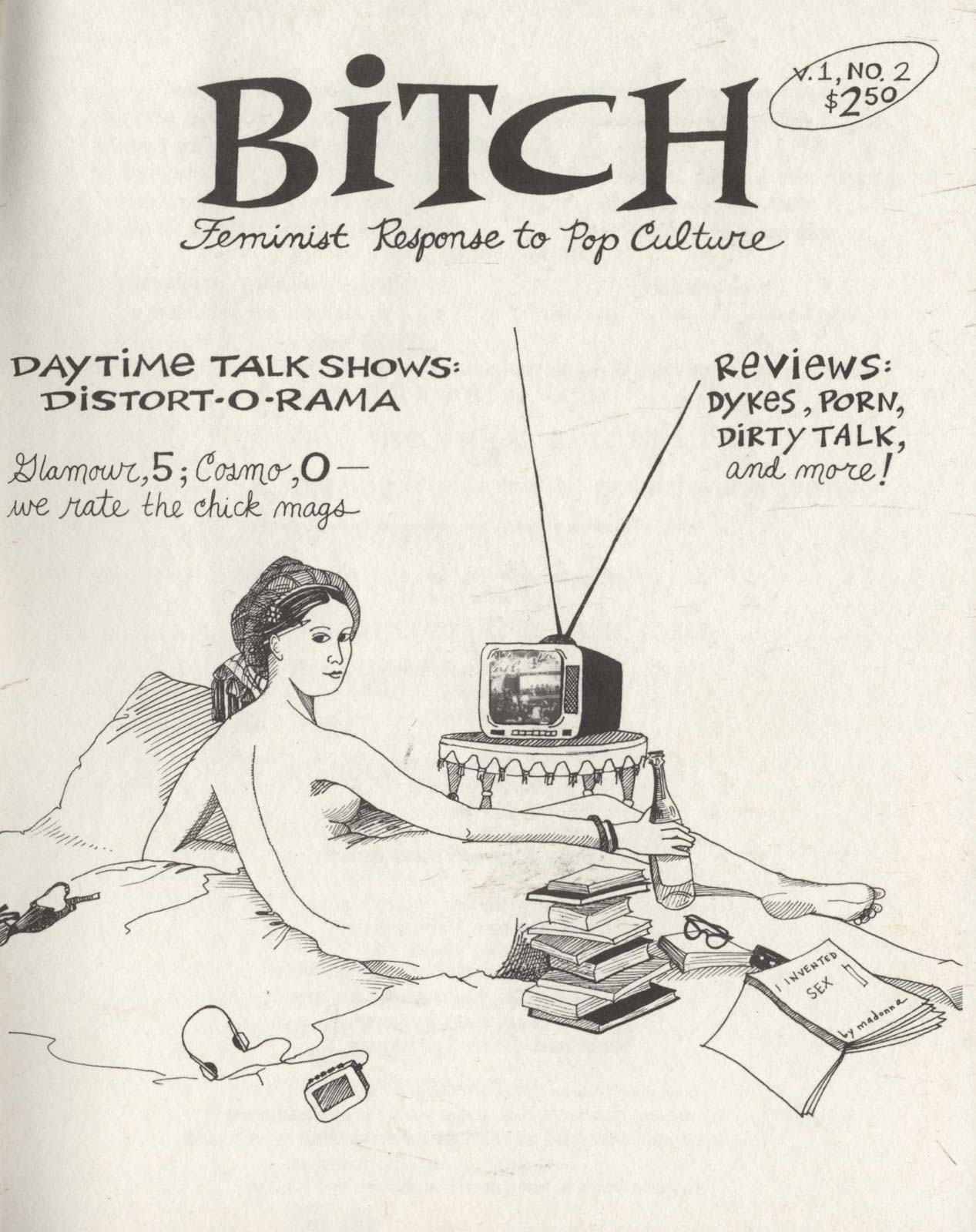

The do-it-yourself publications known as zines have a strong base of support at Barnard. The collection encompasses a wide swath of personal and political publications on body image, the queer community, the feminist punk movement riot grrrl, sexual assault, and more. Magazines with a feminist/rebel ethos are no strangers to Barnard Library’s stacks. Among the library’s collection are Bust (self-described as a magazine that covers music, news, crafts, art, sex, and fashion from an independent, third-wave feminist perspective) and $pread (a magazine by and for sex workers and those who support their rights).

The edgy teen glossy ... was an oasis of real-girl feminist power and celebration in a sea of magazines that featured the prevailing themes of the day — namely, how to be thinner, prettier, smarter, and more appealing to boys.

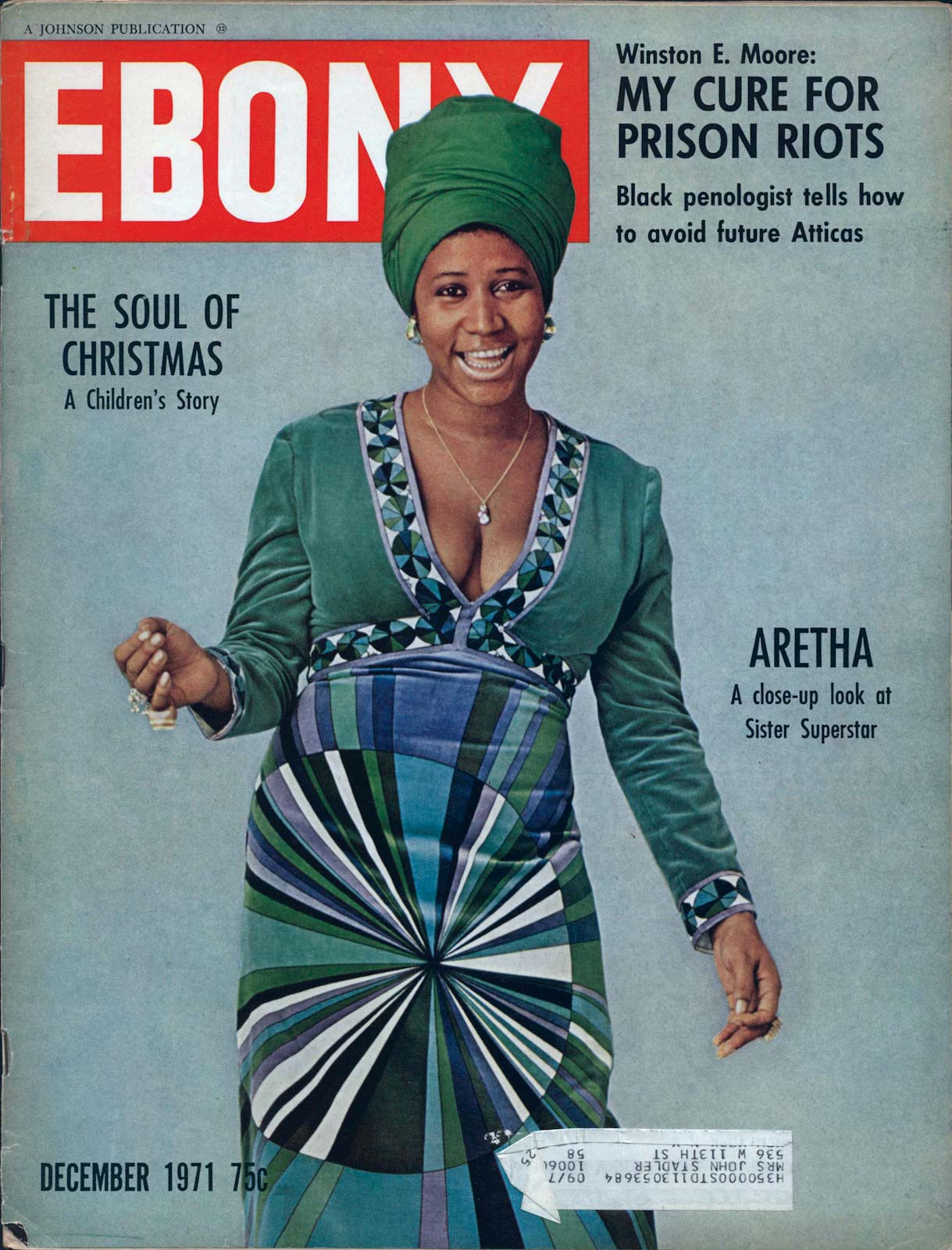

In addition to Barnard’s extensive zine library, Freedman has made an effort to bolster the College’s collection of iconic general and special-interest magazines — among them, Ebony, which covered the lifestyles and accomplishments of influential Black people in fashion, beauty, and politics and is now back on newsstands under new ownership. Ebony has a new, permanent place in the stacks, thanks to a legendary professor. When Barnard Africana studies and English professor Quandra Prettyman died last year, her daughter, Johanna Stadler, made Prettyman’s extensive collections available for the library to review. Prettyman had a collection of issues of Ebony (and Gourmet). Freedman claimed four nonconsecutive calendar years of Ebony to supplement the library’s digital access.

“For most of Ebony’s run, the magazine was a large format, which feels different when you’re holding versus beholding it. I think there’s also value in seeing how the pages have faded a bit over time,” says Freedman. “It’s a visual, and maybe even olfactory, reminder that the item the researcher is viewing is of a different time, perhaps older than they are.”

If magazines best represent the time in which they were created, then Sassy is the ultimate avatar of its era.

The magazines in the library’s eclectic collection are, for the most part, no longer in print but live on as primary and secondary sources for Barnard researchers and students. Freedman expects students will tap into the Sassy collection for a range of projects, from researching ’90s, third-wave feminism to the popular culture and fashion of the era.

Barnard associate professor of history Andrew Lipman followed Freedman’s hunt for Sassy issues and helped by retweeting her posts on social media. “It interested me just because, you know, I grew up as a teenager in the 1990s. And my older sister had a subscription to Sassy,” explains Lipman. He says that as a preteen boy, he, too, could tell Sassy offered a unique perspective.

“It was just a totally different kind of magazine because it was taking a feminist point of view. It had something of an aesthetic that I didn’t realize then, but I think I can recognize now, was sort of influenced by zines,” says Lipman. “I advise senior thesis projects. I would say [if you’re exploring] ’90s young women’s feminism, [Sassy] is a pretty important source.”

A special report in the fall 2021 issue of the Columbia Journalism Review points to “Sassy’s progeny,” including the publications Jezebel, The Hairpin, Worn, Feministing, Bitch, and Bust. The article — “Teen Vogue: OK, Seriously” — pays particular attention to Sassy’s most popular current offspring and notes that “Teen Vogue has surpassed even Sassy’s political chutzpah.” Media analysts note that Teen Vogue has even more forward-thinking, inclusive content.

There’s no denying that Sassy made its mark: “If magazines best represent the time in which they were created, then Sassy is the ultimate avatar of its era,” wrote Jesella and Meltzer in the final chapter of their book.

Freedman believes the addition of Sassy to Barnard’s collection adds an important layer to a multidimensional understanding of female empowerment. “By having several of these publications together, we’re putting feminists from different eras and generations in conversation with each other,” says Freedman.