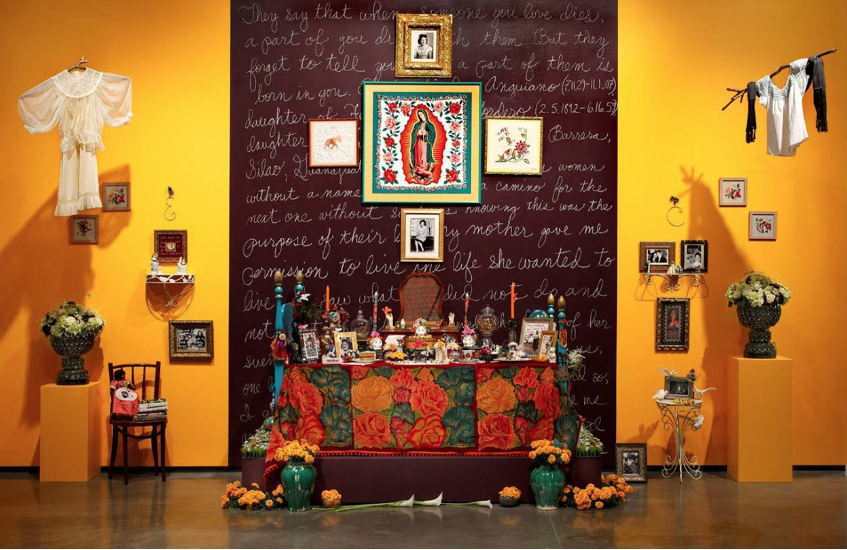

Dia de los Muertos (“Day of the Dead”) in American popular culture is becoming more visible as a magical time when sugar skulls, vibrantly dressed skeletons, and colorful face paint are the main attractions. Barnard will commemorate Dia de los Muertos by hosting a mariachi band on Friday, November 1, 2019, on Futter Field. The musicians will also build an “ofrenda” (“offering” that features loved ones’ photos and favorite items) — all are welcome to add to the community ofrenda.

With such a vibrant display of tenderness in loss, curiosity is bound to follow. How many know the history behind the sacred Mexican holiday that honors the dead? Or of its connection to Halloween, which coincides with Dia de los Muertos (October 31-November 2, 2019)? Professor of history José Moya — who also serves as the director for Barnard’s Forum on Migration and the Institute of Latin American Studies at Columbia — will help to shed light on the subject.

Moya — who teaches courses on global migration, Latin American history, the Jewish immigrant experience, and anarchism — has authored more than 50 publications on Latin America, including the award-winning Cousins and Strangers: Spanish Immigrants in Buenos Aires, which was the subject of a special forum in the journal Historical Methods for its contributions to migration studies; World Migration in the Long Twentieth Century, co-authored with Adam McKeown; The Oxford Handbook of Latin American History, an edited volume on Latin American historiography; and Immigration Culture and Socioeconomic Development in the United States, Canada, and Latin America, which was published in China.

Moya — who teaches courses on global migration, Latin American history, the Jewish immigrant experience, and anarchism — has authored more than 50 publications on Latin America, including the award-winning Cousins and Strangers: Spanish Immigrants in Buenos Aires, which was the subject of a special forum in the journal Historical Methods for its contributions to migration studies; World Migration in the Long Twentieth Century, co-authored with Adam McKeown; The Oxford Handbook of Latin American History, an edited volume on Latin American historiography; and Immigration Culture and Socioeconomic Development in the United States, Canada, and Latin America, which was published in China.

For this Dia de los Muertos “Break This Down” interview, Moya explores the holiday’s history, its commercialization, and the complicated practice of appropriation. So where does that leave Barbie and Coco?

What is the historical significance of Dia de los Muertos, also known as the Day of the Dead?

The Dia de los Muertos is a holiday in Mexico, celebrated particularly in the most indigenous regions in the south of the country — [which are] coincidentally, also the regions of origin of most Mexicans in the New York metro area, in contrast to the Southwest, where they traditionally came from northern Mexico. The specific holiday derives from a mixing of Aztec and Christian traditions.

But venerating the dead may actually represent the oldest and most widespread human ritual practice. Ritual burials and gifts dating back 100,000 years have been found in what is today Israel. We are the only species in all of nature that buries, embalms, cremates, etc., their dead, in part because we are the only ones capable of conceiving abstract, metaphysical concepts such as an afterlife. Holidays similar to the Dia de los Muertos, which honor dead ancestors in ways more festive than solemn, appear in many religious traditions all over the world. These include the Buddhist and Confucian Bon Odori in Japan, the Hindu Gai Jatra in Nepal, the Taoist and Buddhist Zhongyuan, or “hungry ghost festival,” in China, and Allhallowtide in Christian Europe, among others. This omnipresence indicates they embody a basic human quest for both meaning and community.

What would you like for people who are celebrating Halloween to know about Dia de los Muertos?

Both holidays have the same origin: the Christian triduum, a three-day religious observance of All Hallows’ Eve — later contracted as Halloween — All Hallows’ Day, and All Souls’ Day that goes back to the late Roman Empire in the 400s. As with many religious celebrations, this triduum originally fell in the spring and continues to do so in Eastern Christian churches. In the early 600s, however, Pope Gregory III changed the date to October 31-November 2, and all Western Christian churches, whether Catholic or Protestants, still observe those days today. The Dia de los Muertos retains the triduum and involves entire families and people of all ages, while Halloween has become a one-day affair involving parents with children and, later in the day, partygoers.

Mattel recently released a new Dia de Muertos Barbie, and the 2017 film Coco was a big hit, leaving many to wonder about America’s commercial appropriation of the holiday. How best can we understand this concern?

The connection between religion and commerce has a long history — religious festivals were also trade fairs — as do complaints about that connection, as the story of Jesus expelling the merchants and moneylenders from the temple exemplified (John 2:13-16). The Dia de los Muertos is no exception in this regard. Food, toys, and ornament vendors have always been part of the festivities in Mexico, and commercialization has intensified with supermarket chains, banks, TV stations, and all sorts of companies using the holiday to advertise and sell their products and services, much like with Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Christmas in the U.S.

Appropriation is an equally ancient and complicated practice. Christianity itself consists of a Jewish base with copious appropriations from Greek idealistic philosophy, Egyptian mythology (particularly the figures of Horus, Osiris, and Isis), and Mithraism, based on an Iranian/Roman deity that was born in a grotto, to a virgin, on December 25, and had 12 apostles. Both the Dia de los Muertos and Halloween emerged from the appropriation by the Catholic Church of Samhain, a pagan celebration of the end of harvest common in Scotland and other Celtic regions of Europe.

Most Latin American countries outside of Mexico are more likely to appropriate Halloween, which is particularly popular in the Caribbean, than the Dia de los Muertos. And most Mexicans think that Coco is a Mexican movie because it takes place in Mexico, was premiered there, and has an all-Latino cast. The reality is that there is no such a thing as pure or original cultural practices. They are all hybrids: amalgamations of borrowings, appropriations, and exchanges. The only valid question is not if, but when, and how they mixed; and the same is true for human groups.

What are the stories behind the sugar skulls and La Catrina, two of the holiday’s most popular symbols?

The skulls were a common symbol in both Amerindian and Spanish culture. Italian missionaries introduced sugar art in the 1600s, and this blended in Mexico with similar Arab traditions that came from Spain. Colorful sugar skulls with big happy smiles became part of folk art often placed on homemade altars as tributes to deceased family members. Over time, they have also become industrially produced candy sold in supermarkets — part of the trend toward commercialization.

The figure of La Catrina originates in lithographs with a political intent made by Mexican journalist José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) in the 1910s. The figure of the skeleton challenged racial categories and class distinctions by exposing the sameness of all humans. With its dapper appearance, latest French fashion, and exaggerated makeup to whiten its appearance, the figure also poked fun at Mexico’s adulation of Europe and whiteness. Not accidentally, this critique coincided with the early days of the Mexican Revolution and its exaltation of the country’s indigenous and mestizo culture, a trend that would find a visual expression in the art of Diego Rivera — who actually named the skeleton Catrina — and Frida Kahlo, among others. The strong political component of the original figure, however, has sapped over the years.

How should Americans celebrate Dia de los Muertos, keeping in mind today’s political climate?

It may be difficult to politicize the Dia de los Muertos. Unlike Cinco de Mayo, which celebrates the defeat of French invaders in Mexico, it does not relate to national identity or symbols, such as flags and anthems, so would be difficult to tag it as an alternative or opposition to U.S. patriotic holidays because it has nothing to do with patriotism.

Moreover, although the holiday has experienced some of the commercialization and secularization associated with Halloween (for many it is just an occasion to put on extravagant costumes and party), it has retained more of the Christian connection, so it should be, if anything, welcomed by Evangelicals or religious persons in general. It is also more family oriented — presumably another plus in the eyes of more conservative Americans. Last but not least, it is a delight to the senses.

Watch the video below of professor Moya discussing why he teaches:

In the NYC area, Tamara Geisler '10 and her mother, Irma Bohórquez-Geisler — the founder, artistic and program director of the New York City Day of the Dead Festival on Staten Island — host the largest Day of the Dead programming of its kind. For the past 20 years, Geisler has been the main Teaching Artist for the event, where she leads workshops on folk arts and crafts, such as papel picado banners, skeleton puppets, and paper marigold flowers.

Barnard experts explain.