The faces of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) have traditionally and largely been white and male, and the recent U.S. Census statistics confirm that is still the case. While women make up nearly half of the U.S. workforce, the male STEM contingent remains at 73%. There are many theories as to why, but one thing is clear: Women are facing formidable challenges in the pathways to STEM careers.

Barnard is among the institutions that are changing that picture. From the College’s Science Pathways Scholars Program, known as (SP)2, to alumnae who stand out in their respective STEM fields, there’s reason for optimism. In this article, and in celebration of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science (February 11), you’ll find inspiration in how these women are bringing more diversity to the fields of STEM.

Closing Gaps in Rural America

Susie Spikol ’90 was always interested in the environment and loaded up her Barnard schedule with related classes. Still, her major was English literature, mostly because she wasn’t quite sure how she would apply her passion for the environment to an actual career. “I never saw female role models in the field,” she says. “Jane Goodall, maybe, but that was about it.”

Spikol also admits that she lacked confidence in her math and science skills, a likely result of the traditional teaching methods during her middle- and high-school years. “I can remember doing labs in middle school where I was told to be the ‘note taker’ because I had neat handwriting, while the boys were handling the burners,” she says. “Research shows this is the age where girls usually drop out of science, and it becomes a very male-dominated world.”

While Spikol eventually did make a career out of her love of the natural world — she’s currently a naturalist and a community programs director at the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, New Hampshire — she wanted to make sure today’s young girls didn’t fall through the cracks as she did. The result is her pet project, Lab Girls, an afterschool program designed to help middle-school girls stay in love with STEM.

Sharing a Love of Nature

Spikol’s path to her current career involved a series of different jobs and experiences, each building on the next. While at Barnard, she interned with the Central Park Conservancy, working with naturalists who taught young students about nature in the park. Post-graduation, Spikol took a job at a youth residential center for environmental education, living and teaching 24/7, which didn’t leave time for anything else in her life. “I loved the work but also realized it wasn’t really sustainable long term,” she says. “I asked around about career paths and eventually applied to Antioch University, getting a master’s in environmental studies.”

The combination of her English lit degree and her master’s prompted Spikol to recognize the importance of communication in environmental science. “The natural world needs someone to speak for it,” she says. “I was inspired by women who wrote about nature and realized there was room for a holistic approach. I spent a lot of time thinking about my time at Barnard and what a treasure it was to dig into a topic and fall in love with it.”

All of these experiences helped Spikol develop the formula for Lab Girls. A standout feature of Lab Girls is that Spikol established it with a rural setting in mind. “I grew up in Brooklyn and had lots of opportunities to go to museums or participate in programs that interested me,” she says. “In rural areas, girls generally don’t have those museums or university-sponsored programming, so they don’t get many opportunities to learn about careers in STEM.”

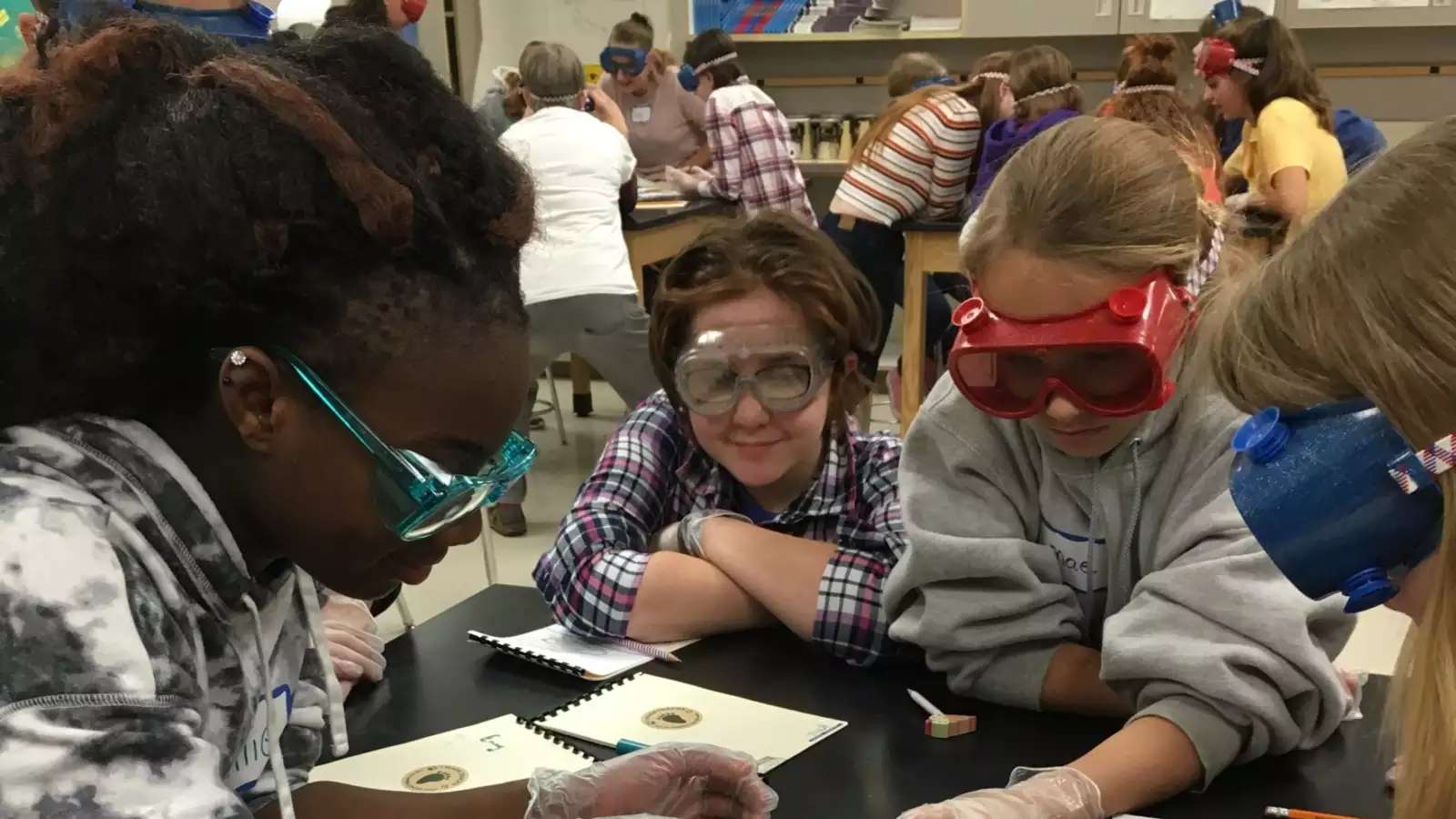

Lab Girls is hoping to fill that void in New Hampshire. At the moment, Spikol runs Lab Girls in a school district encompassing 11 surrounding rural towns. Participants are fifth through eighth graders, and sessions run weekly for six weeks. “We bring in women who are in STEM careers and let them talk about their work, how they got there, and what they like about it,” she says. “They share tips for getting into the field and also include a hands-on component for the girls.”

Recently, for instance, an owl researcher worked with the girls, teaching them how to identify calls, take apart a pellet, and help them interpret owl behavior. “I really want this to be a safe space for girls to mess around with the tools of science,” Spikol explains. “It’s compelling for these girls to see female role models and imagine themselves in a similar career.”

In addition to the specialists Spikol invites to speak with students, she recruits high school girls to serve as mentors to the younger students. Soon the program will expand into two other districts in the region, and as a result of the pandemic, Spikol was inspired to add a remote/virtual option, which was enthusiastically received. “We had about 175 girls sign up, which was huge for us,” she says.

Spikol got the program off the ground initially after winning funding from a local women’s organization with a “shark tank” approach. “I pitched the idea and walked out of there with $11,000 for my organization,” she says. “It has taken off since then.”

While the program is gaining traction, Spikol knows there’s still a long road ahead in increasing women’s representation in STEM. “When you look at the recent U.N. Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, you see that most of the protestors are female,” she says. “But when you look at the table of leaders, it’s mostly male. We still have a long way to go to gain a seat at the table.”

I really want this to be a safe space for girls to mess around with the tools of science. ... It’s compelling for these girls to see female role models and imagine themselves in a similar career.

Making a Difference in Africa

Although Sesae Mpuchane ’72 grew up on the other side of the world from Susie Spikol, both women share a love of STEM and a dedication to bringing more young girls into the field. Unlike Spikol, Mpuchane pursued a STEM career from the outset, entering Barnard on a scholarship to study biology in 1968. Now retired, Mpuchane has left an indelible mark on the field of STEM in Botswana.

Before heading to the United States for college, Mpuchane did her primary and secondary education in Swaziland, after emigrating there with her family from South Africa at age 8. While at Barnard, she says, Mpuchane “connected with people from various nationalities and was able to share with them the challenges faced by many women in various countries. Barnard gave me an international outlook to problem solving.”

Following graduation from Barnard, Mpuchane became a graduate assistant at the Black Studies Institute at Ohio University. “Through that program, I registered for an MSc degree in medical microbiology while assisting undergraduates from disadvantaged communities improve their biology competencies,” she explains. “That exposure helped me develop a keen interest in education and a teaching career.”

Upon completing her studies at Ohio University, Mpuchane returned to Africa, applying for a position in the biology department at the University of Botswana. It was here that Mpuchane noticed something amiss in the STEM fields. “I was struck by the low participation of girls and female academic staff in STEM programs,” she says. “I took an interest in programs, activities, and organizations that addressed issues of lack of parity of women in STEM.”

Additional education pursuing a Ph.D. in food microbiology at the University of Surrey in the U.K. further cemented Mpuchane’s belief that girls were too often left out of the STEM equation. “I realized the lack of parity was universal,” she says.

Motivated to change that imbalance, Mpuchane took on the role of coordinator for the University of Botswana’s program called Women in Science (WIS). In this position, Mpuchane began chipping away at the low representation of young girls in STEM programs.

The Same but Different

From her time in the States and then in Botswana, Mpuchane had the unique vantage point of comparing and contrasting the lack of STEM career paths for young girls in both countries. “The situation in Botswana is similar to that in many countries, including the United States,” she says. “There are more girls than boys at the primary, secondary, and tertiary level of education. Generally, girls also outperform boys in many courses, except in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. Fewer girls then participate in these programs.”

Through WIS — which Mpuchane coordinated between 1999 and 2003 — she collaborated with Botswana’s ministry of education as a way to get the word out about the STEM programs. “That partnership was very beneficial, as we were able to reach thousands of young girls,” says Mpuchane.

Results of Mpuchane’s efforts are wide reaching. During her tenure with WIS, the project published seven booklets to prepare girls for careers in fields such as engineering, mathematics, computing, and agriculture. One booklet targeted parents to assist them in encouraging their daughters in the STEM disciplines, and another profiled several Botswanan female scientists. Additionally, WIS held career fairs, science clinics, visits to secondary schools, a mentorship program, and a regional conference that brought together South African and U.S. women scientists to address gender imbalances in STEM. Other resources included a mentorship program and partnerships with universities in the States that run similar programs.

Mpuchane’s efforts have not gone unrecognized. In 2005, the U.S. Embassy awarded her the Botswana Vanguard Women Leaders award, and in 2016, the Botswana Academy of Science named her a fellow.

Even in retirement, Mpuchane continues to actively encourage young girls to pursue careers in the sciences. “I’m associated with various groups and institutions working to bring parity in STEM participation,” she says. “I make presentations and participate in workshops and science fairs and encourage young girls to form science clubs.”

The work has paid off. “There are a number of organizations and institutions addressing the problem,” she says. “Today there is gender mainstreaming, positive action, and data to support those efforts.”

—This article, by Amanda Loudin, is courtesy of Barnard Magazine’s Winter 2022 issue.