In 1989, the Exxon Valdez supertanker spilled 11 millions gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound; oil lingered at the site for decades. Though the disaster continues to affect wildlife generations later, remediation occurred naturally. As of 2015, only 0.6% of the spill remained, with much of the cleanup credit going to natural processes.

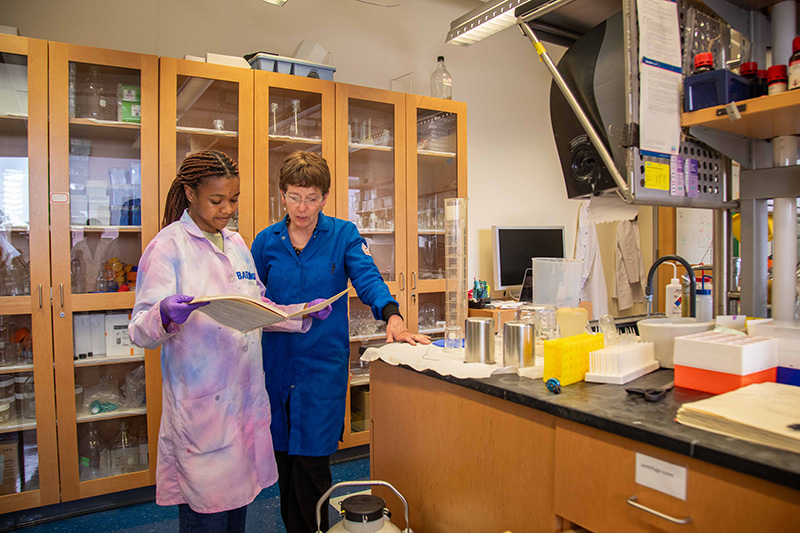

For the past 20 years, Diana T. and P. Roy Vagelos Professor of Chemistry Rachel Narehood Austin has worked with students in her lab to examine how nature cleaned up our mess. One of her primary research goals at Barnard has been to reveal an oil-degrading enzyme, alkane monooxygenase (AlkB), in its 3-D active state. The paper, “Structure and Mechanism of the Alkane-Oxidizing Enzyme AlkB,” was published this past April in Nature Communications.

Austin said the primary reason for solving the structure of the enzyme was to understand its structure and function. It’s particularly important as the enzyme functions in the global carbon cycle, which is critical to the planet’s habitability. The enzyme carries out the first step in metabolizing one form of organic carbon into carbon dioxide.

The goal of the work is not to inhibit the enzyme to prevent carbon dioxide from going into the atmosphere, rather it’s to gain a better understanding of the carbon cycle itself. How AlkB influences the cycle’s functions is subtle. Austin said the active 3-D version is an important element in the scientists’ toolkit for fully deciphering the carbon cycle.

“There’s this whole question mark of what’s actually happening in our environment,” she said “And if we don’t understand the process of what’s happening, then it’s really hard for us to predict how human activities can change it.”

Several student-researchers assisted Austin on the project, but she credits three alumnae — Juliet Lee ’21, Shoshana C. Williams ’20, and Allison Forsberg ’20 — for helping her bring this structure to fruition, alongside her in the lab, and serving as co-authors of the recent paper. All three are pursuing a Ph.D. in chemistry: Lee and Williams, both of whom were Beckman Scholars, are continuing their studies at Caltech and Stanford, respectively, and Forsberg went to USC. The alumnae’s professional achievements underscore Austin’s parallel priority — teaching students how to become scientists, how to handle successes along with failed experiments, resisting outside pressures, and maintaining the long view.

“They’ve known [AlkB has been] a key ingredient in the bioremediation of oil [for 80 years], but nobody has known about the three-dimensional structure,” said Austin. “So, 20 years seems like nothing to figure that out.”

Austin has always been intrigued by the interface between the environment and chemistry. While scores of scientists work on the environment in countless capacities, Austin’s niche in this area is that of an inorganic chemist interested in the role of metals in biological systems.

Shortly after Austin joined Barnard in 2015, a mutual colleague introduced her to Liang Feng, a professor of molecular and cellular physiology at Stanford. A postdoctoral fellow in Feng’s lab, Xue Guo, had solved the three-dimensional structure of a protein she thought might be AlkB. This protein was out of Feng’s area of expertise, and the mutual colleague thought Austin could help, and she did.

The protein that Guo had purified was crystallized in an inactive form. Eventually, Austin was able to show that the purified protein was active, it just wasn’t crystallizing in its active form — and it was AlkB. Feng, now fully invested in the research, joined Austin’s long-held quest to determine the structure of active AlkB.

“We were holding out to get the active form, because that’s the most important thing [for the environment],” said Austin.

For seven years, the two worked together with several students in Austin’s lab. Lee spent two summers at Stanford working side by side with Guo to find a form of AlkB that was easier to characterize in its active form. Finally, more than 20 years into Austin’s research, Feng concluded that the structural data was ready to publish. Austin began writing, and it was, she believed, top journal material.

To get the word out, the team told a story that could be easily followed. “We cut out anything that wasn’t essential, and I think that’s partly why it ended up being so easy to review, because it was a simple story,” she said.

If I can help my students see that we can do really good and fun science and that we can do it carefully and ethically, that’s probably more important than anything else I’m going to do in my life.

During the seven years Austin was examining the inactive structure of AlkB, she had a sense of when she might find the active form. Nevertheless, the discovery has opened up a host of questions. She compared the experience to rock climbing, when a piece of protection is placed in a crevice to secure a climber while she moves up to the next level.

“Without having [the paper] out, I was always torn in multiple directions about how to spend my energy,” she said. “And now it’s really clear what we should do next. I feel like I’m ready for the next 20 years for sure.”

Austin said the active site of the enzyme, the place where the two iron ions are, is “mind blowing.” “Normally if you have two metal ions in an active site, it is really obvious to see how they work together,” she said. “In AlkB, the two iron ions are too far apart to directly work together. So the next thing is to better understand how the active site works.”

Mentoring Barnard Students

Discovery as a process is a lesson she imparts to her students. “Science is hard, and young students make a ton of mistakes, and there’s certainly a temptation for students to say, ‘I want to prove something,’” she said. “I sit them down [and say], ‘You know, that’s really not the point.’”

She said if they do four experiments and they get four different results, that is the reality. In light of recent cheating scandals in the scientific community, she believes that upholding standards like peer reviews and respecting colleagues is just as critical in teaching science as finding the 3-D active state of alkane monooxygenase.

“The end never justifies the means — it’s how you live your life that is always, in my experience, more important than any endpoint,” she said. “If I can help my students see that we can do really good and fun science and that we can do it carefully and ethically, that’s probably more important than anything else I’m going to do in my life.”

On September 7, Austin won the ACS Award for Research at an Undergraduate Institution from the American Chemical Society.

(This article is a slightly edited version of “A 20-Year Research Quest,” by Tom Stoelker, from the Fall 2023 issue of Barnard Magazine.)