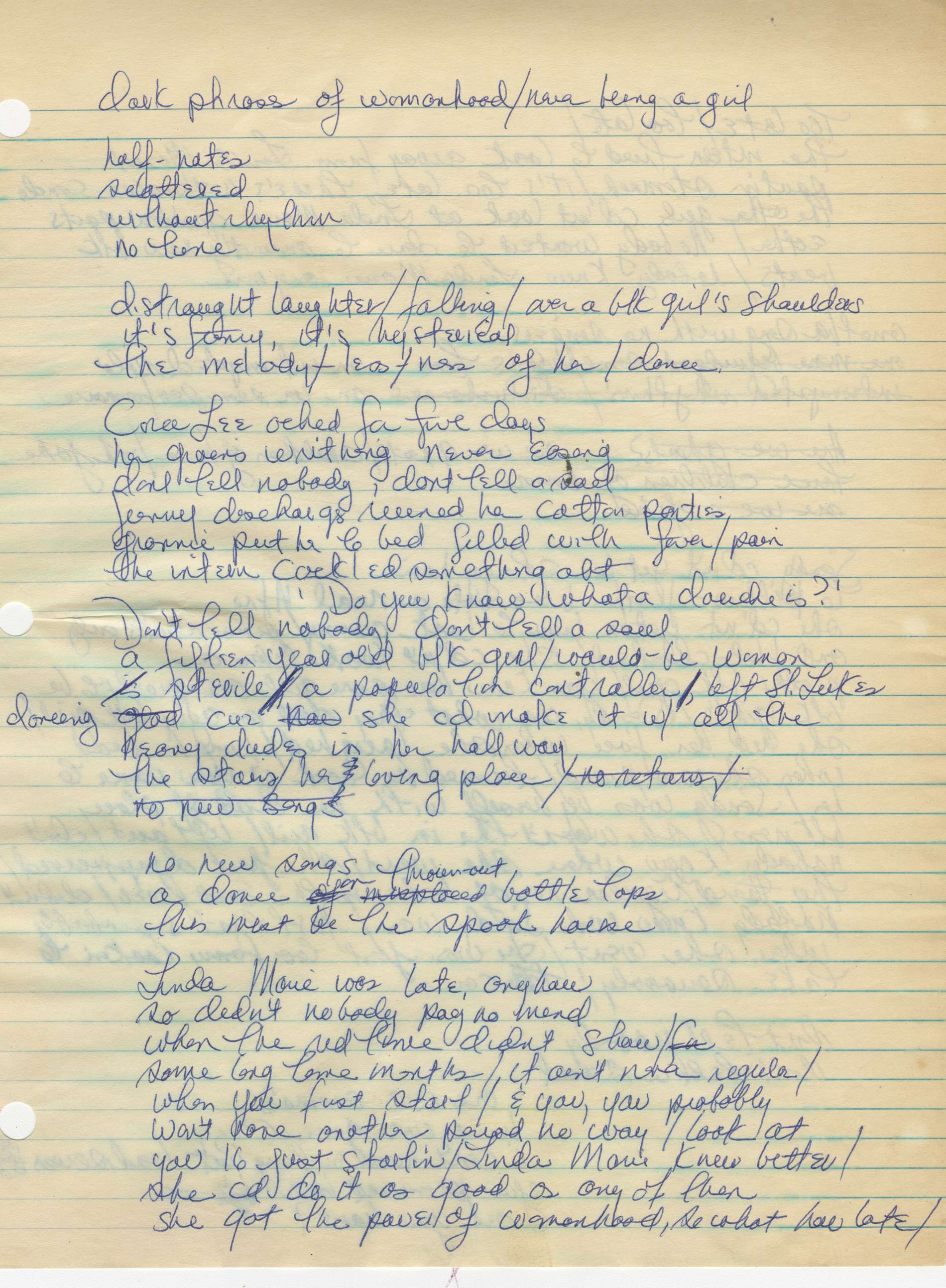

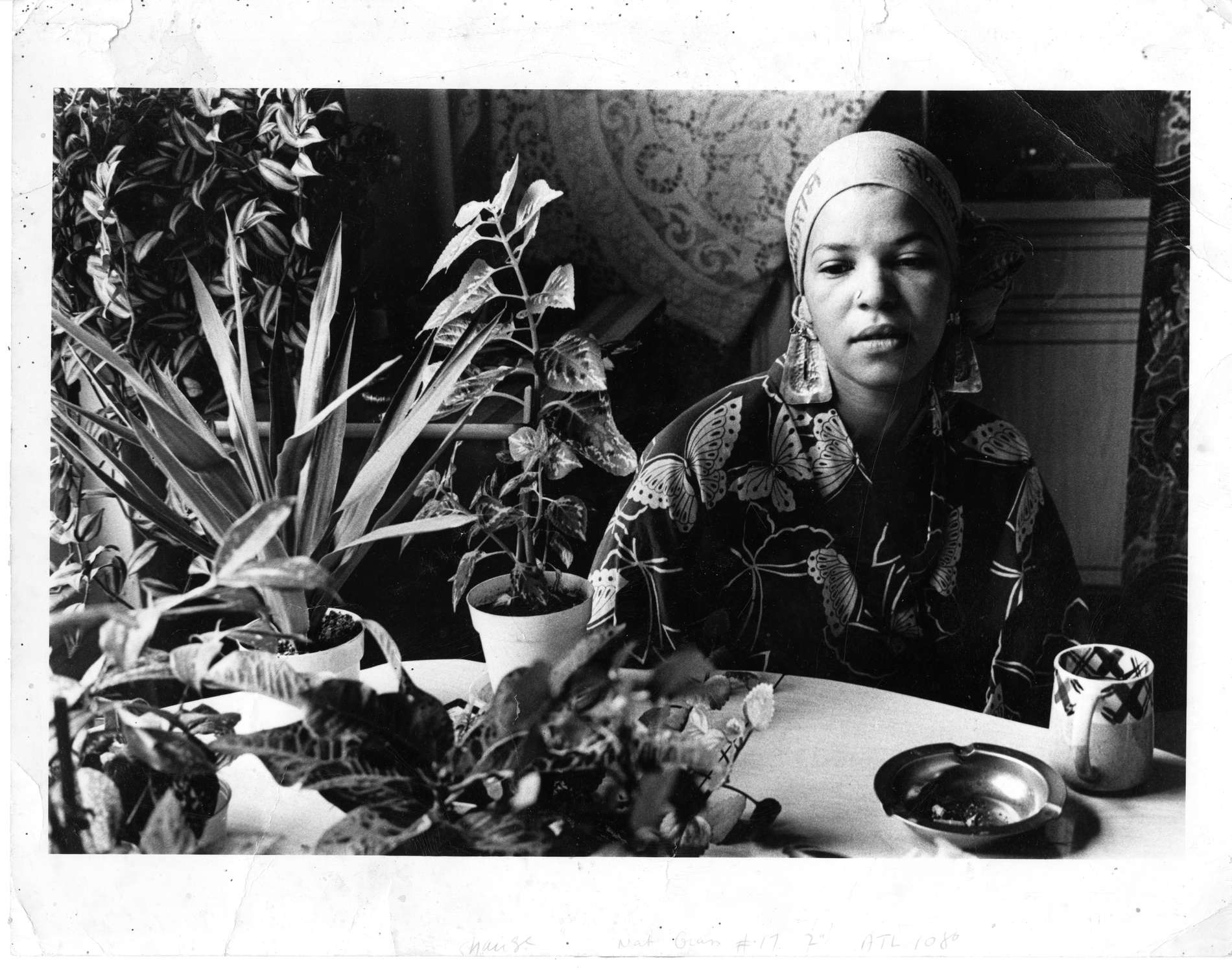

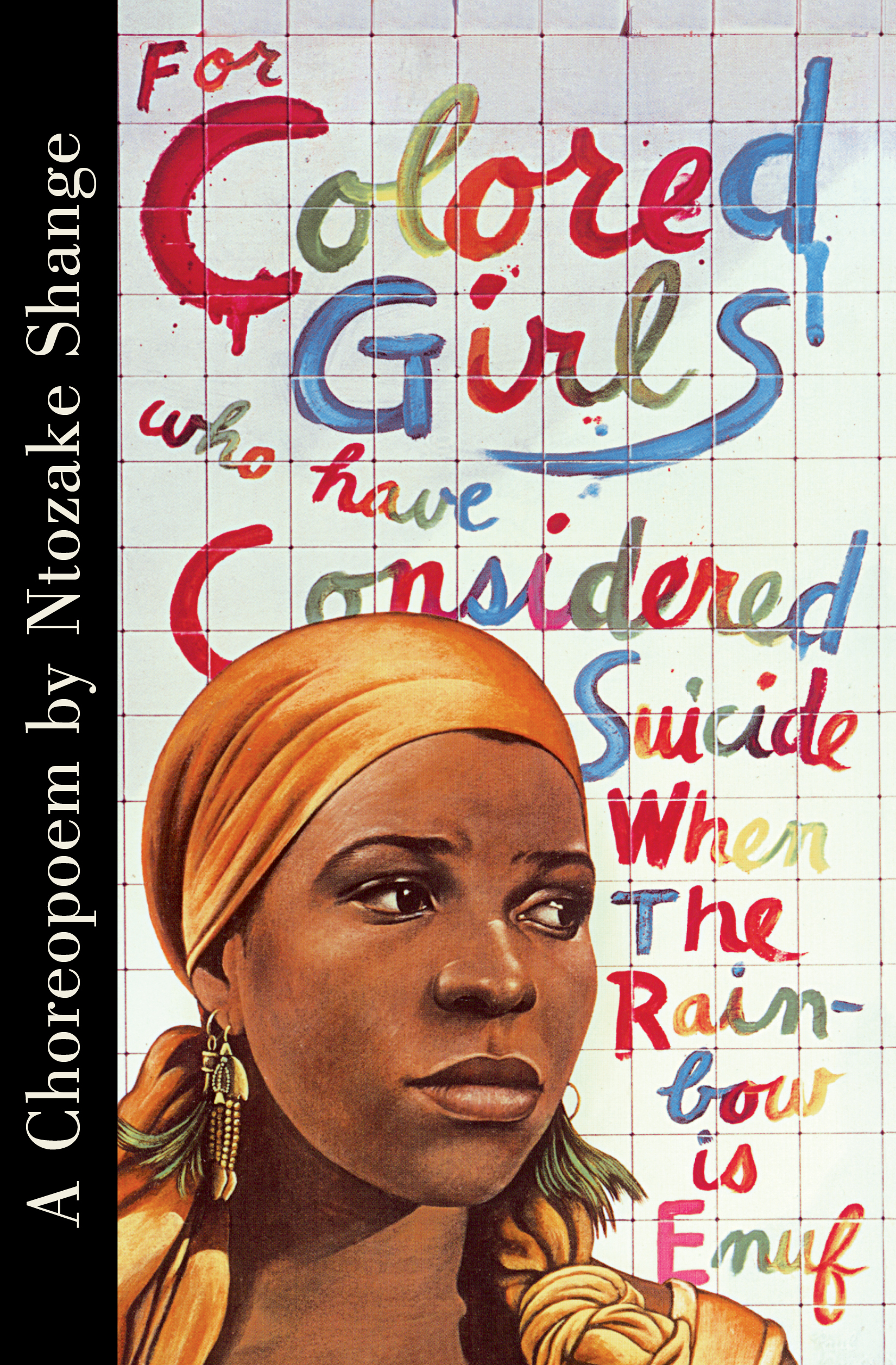

[Photo: Shange, 1976. Photograph © Sylvia Plachy. Reprinted courtesy of the Ntozake Shange Literary Trust.]

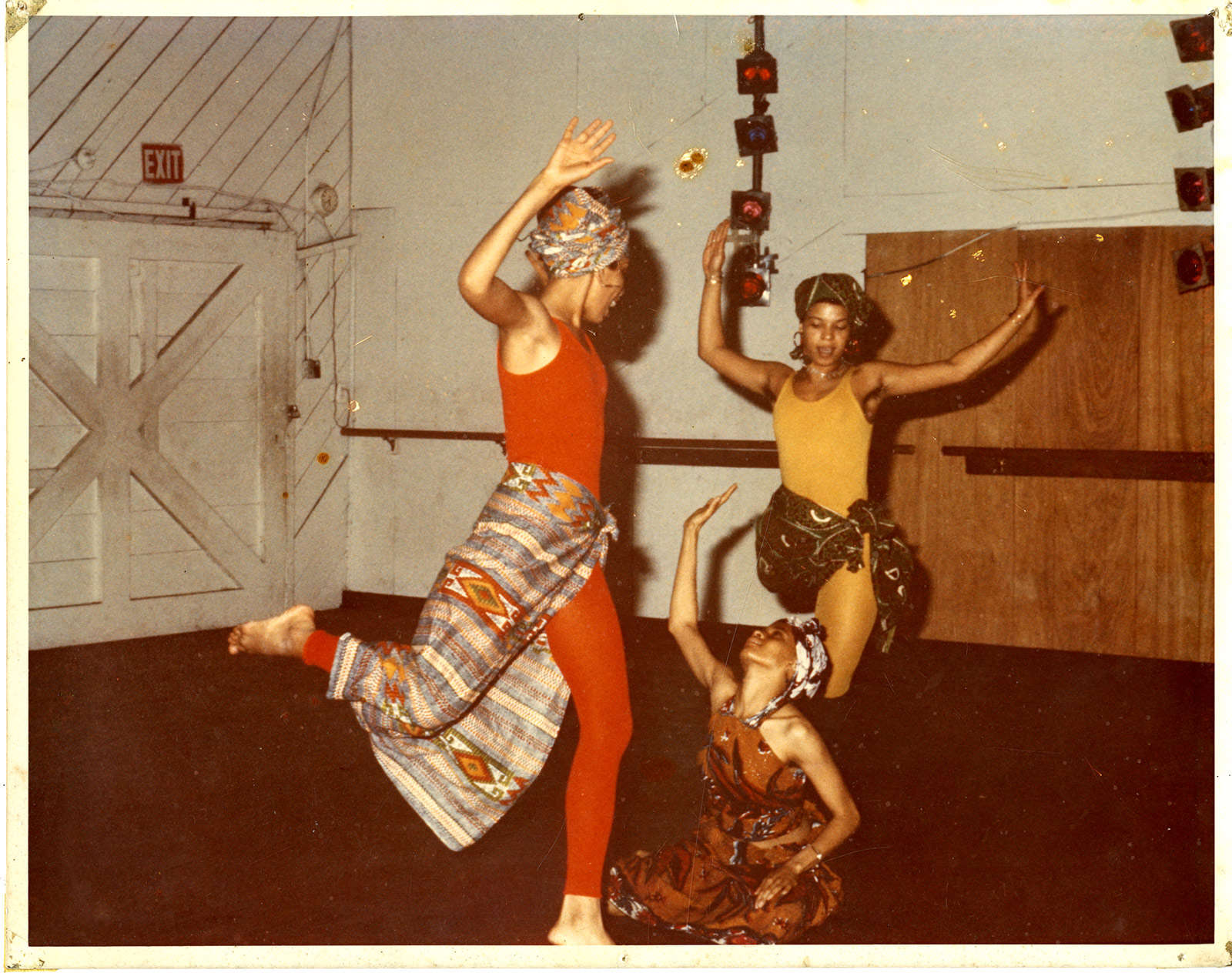

When she was still a student at Barnard, feminist icon, poet, and performer Ntozake Shange ’70 started to sink her teeth into the early manuscript of what eventually became her Obie Award-winning “choreopoem” for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf. A pivotal performance piece that blended movement, music, and spoken word within the structure of a play, for colored girls premiered at The Public Theater in New York City in 1976, the year after Shange published it. From October 13 to December 15, 2019, the Public Theater is producing a return of for colored girls for the first time since it debuted more than four decades ago. Just after the anniversary of Shange’s passing in 2018, at age 70, the seven women on stage — known as Lady in Red, Lady in Orange, etc., for the color of their dresses — brought her vision to a new audience of mostly Barnard students in a special performance on November 19.

The emotional production, directed by Leah Gardner, was delivered on a circular stage by a diverse group of actors, creating a 90-minute immersive experience that is Shange’s bold response to sexism and racism. Always forward-thinking, Shange worked closely with cast and crew on the new production before her death and added a deaf performer as Lady in Purple, who signed her lines, giving movement and voice to a group of women who are literally silenced. The seven women’s costumes were also updated to include portrait motifs of different black women on their dresses — all were personal matriarchs chosen by the respective performers as a way to honor their ancestors. At the play’s conclusion, the theatre jumped to its feet in a standing ovation.

The Public Theater. [Courtesy of The Public Theater. Photo credit: Joan Marcus.]

Shange’s powerful connection to the College was evident by the strong turnout, with 100 students and 60 alumnae in attendance. After the production, the theatre hosted a “talkback” session that included two Barnard faculty members — Kim F. Hall, Lucyle Hook Professor of English and professor of Africana studies, and Monica L. Miller, associate professor of English and Africana studies — alongside members of the cast and Shange’s brother Paul Williams.

“Ntozake loved Barnard, and her time there and in New York was a tremendous foundation for her,” Williams said.

Watch a video featuring reactions to the play from the Barnard community:

Hall, who teaches Shange’s work and recently published an essay in Hyperallergic about the play in the #MeToo era, agreed that the connection is strong. “For the past five years, I have been privileged to teach a seminar at Barnard College, The Worlds of Ntozake Shange, which studies Shange’s writings in the many social, artistic, and political contexts that influenced her life and work,” Hall said. “Students produce final projects rooted in their explorations of the Ntozake Shange Collection, which Ntozake bequeathed to the college in 2016 out of a desire to create a space for the students of the future to know themselves, to learn the sound of their own voices. She would also visit our class, [which was] a key moment when, after reading her work, students could ask her questions and hear her thoughts on the world, on literature, and on the future of political struggle.”

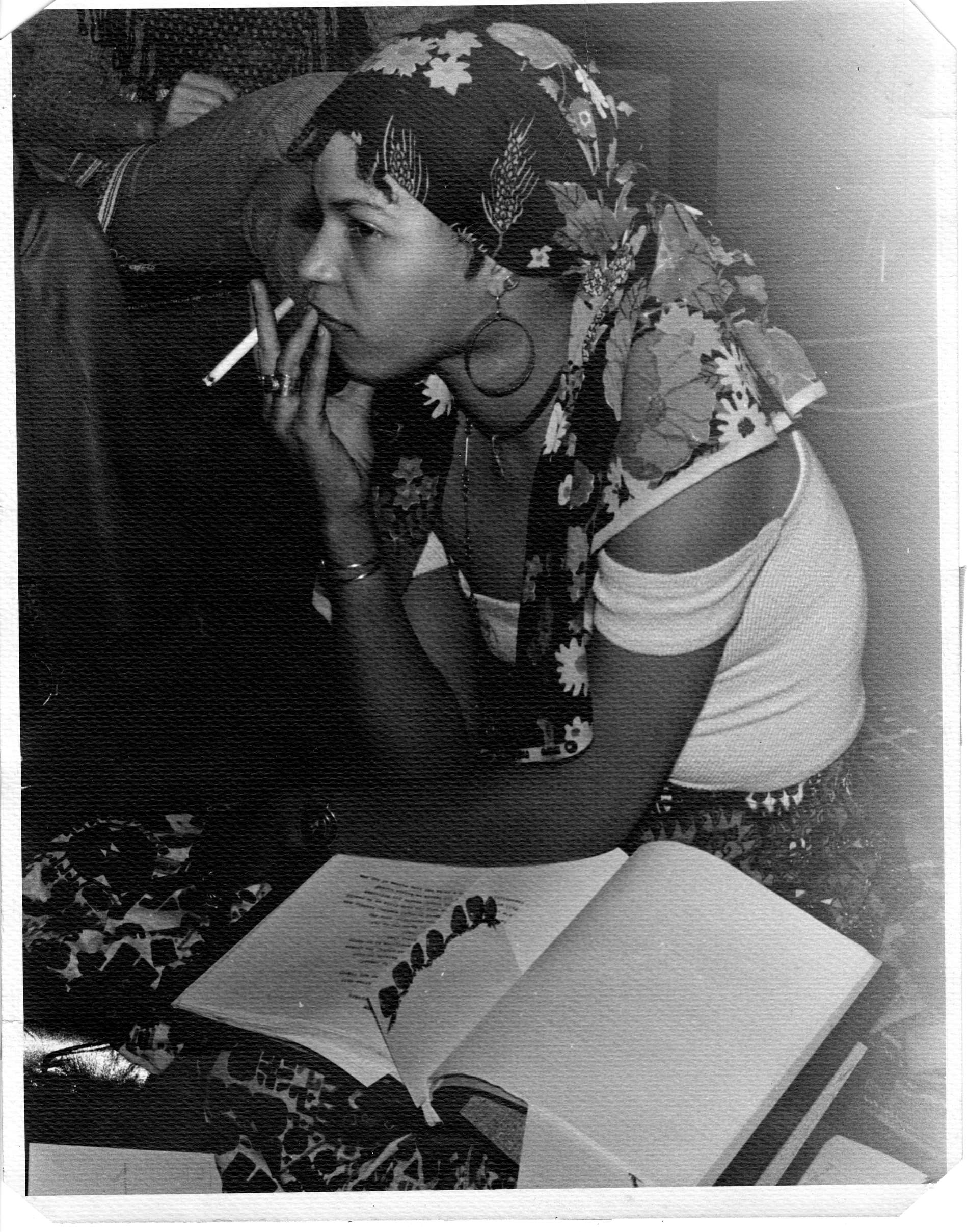

"I feel as though I came of age as a feminist and an artist at Barnard,” Shange told Barnard when she officially donated her collection. “I formed the basis of my critical thinking in English and history classes. I was a member of conscious-raising groups, the antiwar movement, and black student movement. I got all that I ever imagined from an all-women’s college, and I thought my archives belonged here."

“We started working with Ntozake Shange in 2013 on transferring her papers to Barnard,” said associate director of Barnard Archives and Special Collections Martha Tenney during the talkback. “When we think about archives we think about the past, but she also spoke beautifully about the future and wanting to make apparent to students, especially black students, what the future could hold for a student like her at Barnard.”

“Her archives, like her work, are incredibly generous and intimate,” Tenney noted about Shange’s donation to the College. “You can see her creative process, her personal connections, her life as an artist through her papers.”

After the show, Ayana Byrd ’95, who recalled reading Shange and seeing a performance by an all-Barnard cast while at the College, said that since her time at Barnard, she has read the choreopoem many times, to the point of memorization. The current rendition, she said, proved the work’s longevity.

“Even though there were particular things in this play, in 2019, that didn’t exist in the way they did when it was written, it felt timeless, and it also reminded me of the power of Barnard,” Byrd said. “Because [Barnard is] where I first experienced for colored girls, first experienced Ntozake Shange, where I became a woman, and where it’s clearly formed so much of her feminism that I felt was represented. It made me feel great as an alumna to see it.”

Makaria Yami ’21, who has taken Hall’s Shange class, and who also did her final semester project on for colored girls, agreed. “Our class met with Ntozake Shange before she passed, and seeing this play is meaningful to me because I loved her so much,” Yami said. Beaming, she continued, “I also brought my sister, who’s a first-year at Barnard, with me. I’m trying to get her to take the class with Professor Hall. I think it’s also really special to be able to share this experience with her and with other black women at Barnard.”

The slideshow below is a tribute to the play and Barnard’s never-ending rainbow of love for Shange and includes archival photos from her original for colored girls chapbook, written in her own hand, and photographs from her 2018 visit to the College for the inaugural event of the Lewis-Ezekoye Distinguished Lecture in Africana Studies.

— N. JAMIYLA CHISHOLM