Every November, the nation recognizes National American Indian Heritage Month to honor the long legacy of indigenous people in North America. In New York City, there are five sovereign and recognized nations that are Lenape, the city’s indigenous people. Yet due to centuries of genocide, forced migrations, and the environmental destruction of their homeland (Lenapehoking), the Lenape make up a diaspora today.

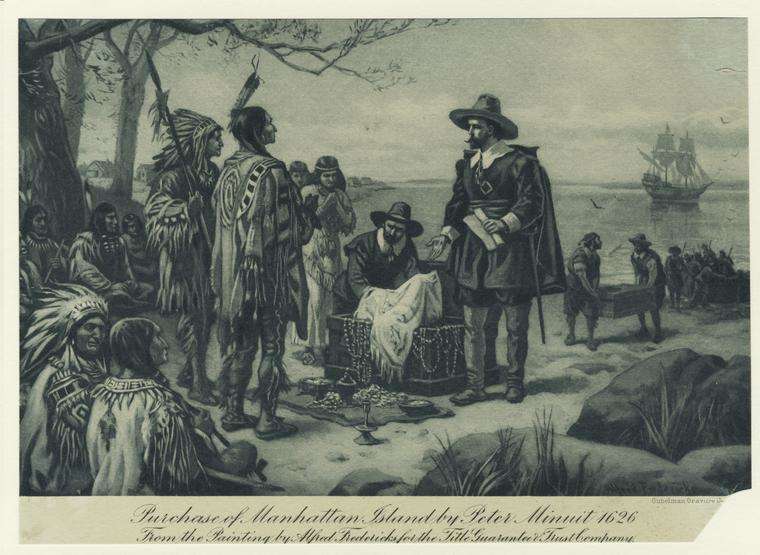

“The ongoing erasure of the Lenape culture, presence, and history has created a vacuum in NYC that has been filled, since the 1700s, with information that is often inaccurate, misinterpreted, misappropriated, and weaponized to uphold racist ideologies to support a still widespread mythology of colonial dominance, such as the sale of Manhattan,” said Hadrien Coumans, co-founder and co-director of the Lenape Center.

The indigenous foundation is so strong in New York City that centuries later, said Andrew Lipman, assistant professor of history, “the largest single concentration of Native people in the United States is in New York City and over a hundred of them are Lenape.” In fact, Bowling Green and the National Museum of the American Indian are both historically important places. Last November 2018, the first United Lenape Nations Pow Wow and Standing Ground Symposium was held at the Park Avenue Armory.

"Not only are there over 100,000 enrolled members of Native communities currently living in New York City, but when you add in the hundreds of thousands more people who are primarily of indigenous descent from elsewhere in the Americas, there are more people of indigenous ancestry living here now than there were in 1609 when Henry Hudson sailed up the river,” Lipman explained. “Indigenous history is not one of disappearing, but it’s an active part of America’s present and future, which is relevant to thinking about how we might see the future of this city.”

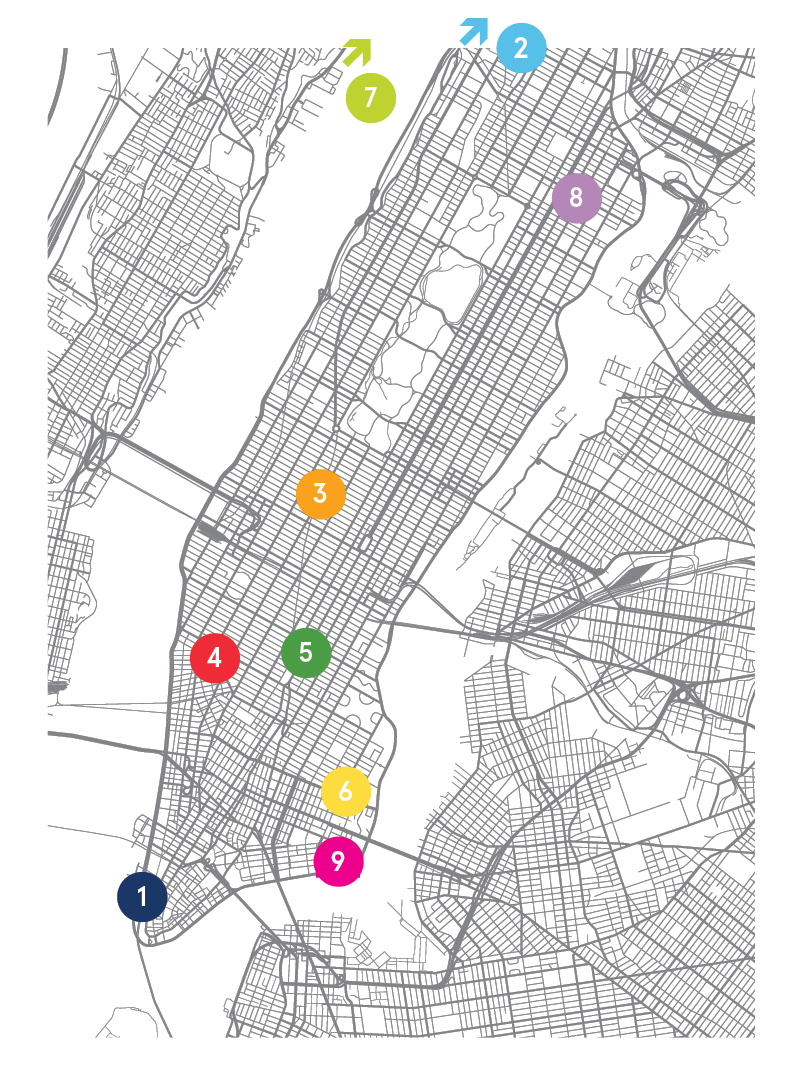

This month, Barnard is featuring a map of Manhattan (below) and slideshow (bottom of page) that includes nine historical points of interests to the indigenous community and to New York City’s residents. Learn more by reading below and then visiting these sites, if possible.

- Bowling Green/National Museum of the American Indian. This park and building stand along the footprint of a colonial fort (hence the name Battery) where delegations of Lenape (and many other Native nations) often met and negotiated with Dutch, then British, colonial officials.

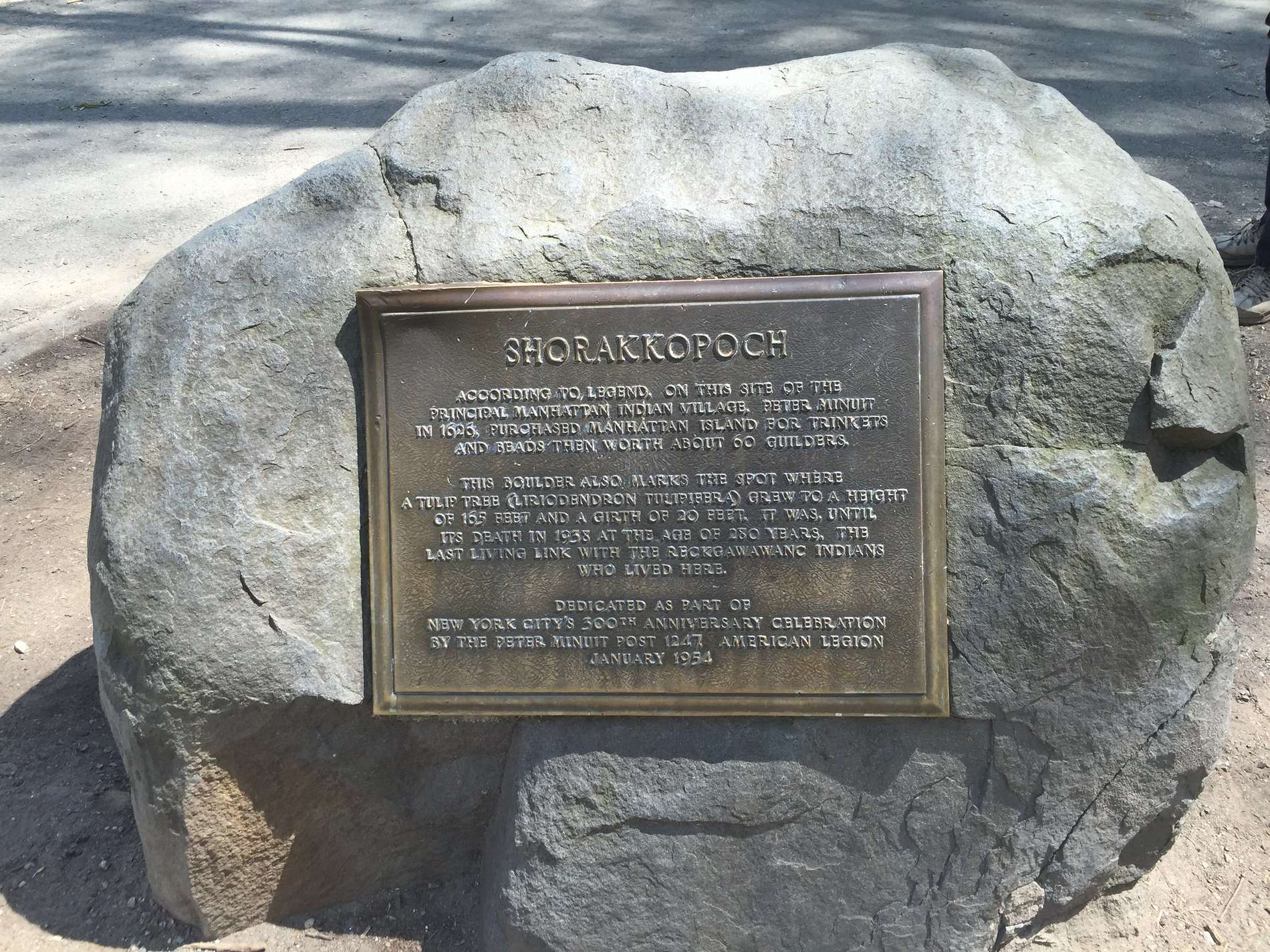

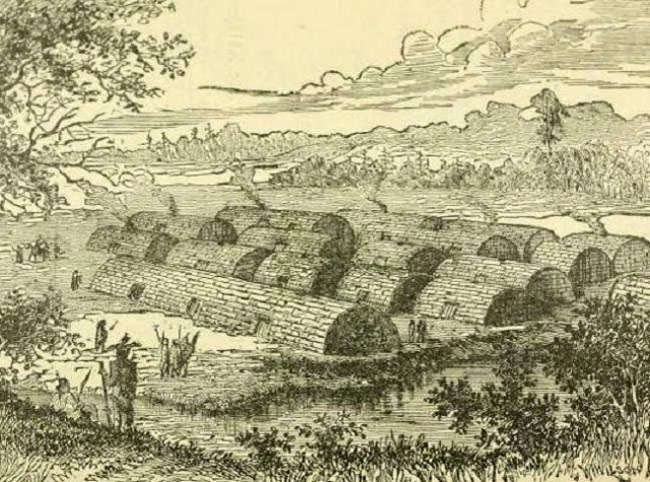

- Inwood Hill Park/Shorakkopoch Rock. The (conjectural) site of a major Lenape village and the reported location of the unlawful 1626 transfer of Manhattan Island from the local Lenape chief to Peter Minuit, the new colony’s director general, by way of the Dutch West India Company.

- Broadway. Broadway was originally a footpath in Manhattan, created by Native travelers. This trail, which ran along the length of Manhattan Island, originally connected different villages to one another and eventually became the road traveled by colonists.

- Greenwich Village. Greenwich Village was once a Lenape village called “Sapokanik,” meaning “tobacco field” or the “land of tobacco growth.” In addition to tobacco farms, the area was an active trading settlement and canoe landing area.

- Astor Place. Known as “Kintecoying” or “Crossroads of Three Nations,” Astor Place was a powwow point for the Lenape tribes of Manhattan. At a sacred oak tree, where the branches of the trails converged, the Lenapes were said to have traded with one another, exchanged news, and held spiritual ceremonies and tribal councils.;

- Foley Square. Lenape villagers were sustained by the Collect Pond before it became the main freshwater supply for Dutch and English settlers. The square was built long after a tannery polluted the pond and slums were erected and then cleared.

- Jeffrey’s Hook. At the narrowest part of the Hudson River between Manhattan and New Jersey, this spot served as a crossing point for Native American mariners for centuries.

- Harlem Plains. The Lenape people may have used this area for hunting deer and other game. The same bedrock from 1609 can still be seen today in Harlem’s Marcus Garvey Park.

- Lower East Side. In February 1643, where the Manhattan Bridge meets Chinatown today, more than 120 Munsees were massacred by Dutch soldiers on what was part of the Nechtank settlement. On July 16, 1906, during construction for the subway, buried dugout canoes were unearthed by the New York Edison Company at the corner of Cherry and Oliver Streets.&