Any conversation about advancing women in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) is incomplete without looking at the unique career barriers experienced by Black women in these fields. Particularly during Black History Month (February), examining the factors that impact and exclude Black women in STEM is critical.

The numbers are striking: In 2013, the National Science Foundation (NSF) released data that show white women hold 20% of jobs in the science and engineering workforce, while Black women hold just 2% of these positions. USA Today reports that although Black and white students of all genders enter STEM majors at about the same rate (20%), Black students leave those majors at a rate of 40%, compared with 29% of white students. Another NSF report on the proportion of STEM bachelor’s degrees attained by Black women shows that they earn about 9% of psychology B.A.s and 7% of degrees in the social sciences, but only 1% of engineering degrees. Additionally, the NSF report indicates that the gap widened between 2004 and 2014.

These disparities have wide-ranging implications, impacting everything from women’s median income to the quality of science itself, especially given that we know that diverse teams produce better outcomes across industries. To delve deeper into what’s preventing Black women from pursuing STEM careers and what might be pushing them out of these professions even after they have secured a foothold, Barnard faculty, alumnae, and students shared their own personal experiences with research and activism, providing much-needed insights into the lack of diversity in STEM. A running theme: Mentors matter.

Have Black women science teachers been able to be their authentic self? The quick answer is no.

Research & Faculty

According to a 2018 Pew study, which looked at white, Black, and Latinx women, the reasons women — Black and Latinx women, especially — don’t enter STEM fields are varied and often depend on the specific field. Research by Alexis Riley, an associate professor in Barnard’s Education Department, indicated that two big factors are that Black students don’t see themselves represented in science education, and Black STEM teachers — particularly women — don’t receive the support that they need as faculty.

Riley pursued a doctorate at Columbia’s Teachers College, where her dissertation explored how sociopolitical factors — such as race, gender, class, and power — inform the pedagogical practices of Black women science teachers, as well as the experiences that Black women science teachers have had in their science education programs and their professional development programs.

Her research drew on her own experiences as a K-12 science educator in Harlem. Starting in 2011, Riley taught social studies, environmental science, and physics. In her social studies class, she guided her students in analyzing hip-hop lyrics, took them to historical landmarks in the city to discuss their implications regarding slavery, and asked critical questions about Christopher Columbus — practicing what she called culturally engaged pedagogy.

This informed how she taught environmental science, after her social studies course was cut. Her science course looked at issues close to Harlem, like food deserts and rates of diabetes. “The theme of my science classes during that time was about learning that there were no accidents and that systemic racism influenced the livelihoods of people of color, but specifically Black and Brown folks,” Riley said. “I was trying to get students to figure out the role that science played in their lives and their families’ lives.”

When she was assigned to teach a physics course with a stricter curriculum, Riley decided to leave the classroom, citing two specific reasons for doing so: First, she felt there was no one at the school who could mentor her in becoming a better teacher. Second, and more alarming, Riley said that watching the 2018 documentary Say Her Name: The Life and Death of Sandra Bland made her realize that “the way that [the police officer] was talking to [Bland], something about the undertones of power, the undertones of control and policing, felt way too familiar to what I was experiencing at school on a daily basis.”

Through her dissertation, Riley explored the forces that push Black women out of teaching science once they make it into the classroom. While analyzing data, a few trends were already clear to her. “If I were to answer the question, ‘Have Black women science teachers been able to be their authentic self?’ The quick answer is no,” Riley said. Part of the problem, she continued, is that “the conversation is not happening in teacher education programs or within professional development. People are doing really brilliant things, but in silos. Sort of like, well, let me close the door and then let’s actually have this real conversation with students.” Riley wants to see those conversations happen in the open.

Riley has learned that the barriers to researching Black women in STEM are as prominent as they are for women working in the STEM roles themselves. Riley credited her mentor, Dr. Felicia Mensah, as a driving force behind her dissertation. “If I would have ended up anywhere else, I don’t know if I could have done this study,” Riley said. “There are so few of us who are as explicit about bringing critical race theory into science education. I am over the moon that Dr. Mensah worked with me, because she’s one of the pioneers in the work.”

Mentorship is also a throughline in the career of the Department of Chemistry’s term assistant professor Jonelle White. “I truly don’t know where I would have ended up without mentorship, and not just any mentorship, the right kind of mentorship for me,” White said. “Getting me out of my own head, getting me out of my own way.”

She first decided to pursue STEM because her two favorite high school teachers taught chemistry and math. She planned to be a high school teacher until a college genetics professor recommended she join a lab research program. Her college also had support programs for minority students in STEM, which she said she wouldn’t have known about if her mentors hadn’t guided her there.

“A lot of people can just fall through the cracks,” White said. “Undergrads really do need guidance to bob and weave through that educational system. There’s so much opportunity, you’ve just got to know what to leverage — because anything can be an opportunity, too.”

White also emphasized the importance of mentors recognizing the specific interests of their mentees, rather than simply encouraging them to follow in their footsteps. While her own principal investigator didn't personally connect with White’s reservations about pursuing tenure-track positions, he supported her finding her own path. White tried to do the same for her students.

“I don’t necessarily encourage people to go my route or to be a tenure track professor,” she said. “Be what you want to be, but find that out. Put yourself in a position to find that out. Don’t just get stuck in one thing because society, your mother, your father, whoever is telling you, ‘You have this knack, and you should do that.’”

We need more opportunities for Barnard students to be in spaces that are historically cis male and white so that we may make our mark on the world.

Students & Alumnae

As liberating as a mentorship can be, research shows that it can only go so far. As Riley pointed out, those partnerships work best in confluence with broader conversations around diversity in STEM. White concurred, noting that the tremendous help of her mentors didn’t safeguard her from encountering a professor in her first year of graduate school who suggested that the program wasn’t a good fit for her when she sought extra guidance on mastering a complex microscopic technique.

With this need in mind, in fall 2020, Rachel Narehood Austin, the Diana T. and P. Roy Vagelos Professor of Chemistry and department chair, co-facilitated the course Chemistry and Racism with chemical physics alumna Lauren Babb ’18, who is a graduate research assistant at the University of Maine working on water treatment catalysis.

The course had four main segments: the landscape of racism in chemistry, representation in chemistry departments in the U.S., the voices and histories of Black American chemists, and strategies for reconstructing organizations to make change. “My intentions for the students were to have a chemistry course that was discussion based, where we could see the value and humanity in one another, under the discussion of science intersecting with elements of social justice,” said Babb.

Looking critically at racial bias in STEM fields is key, said Austin. “Science thrives on dissent and disagreements, which fuel the design of experiments to test hypotheses that deepen our understanding of the natural and physical world,” she said. “Creativity is required to solve scientific problems. For these and many other reasons, we need a diverse group of people doing science. Black women have been systematically excluded from science for too long and at a very high cost to society.”

The subject matter of the Chemistry and Racism course was close to Babb’s lived experience, which was what prompted her to accept the co-facilitation position. She knew there had to be concrete evidence to back up her own anecdotal experiences of racial bias in STEM and that it had to be organized. “I am a Black female chemist, and I had been living my life in these three separate categories, only letting them overlap in the privacy of my own mind,” said Babb. “After the murder of George Floyd, I felt incredibly fed up with living these three separate lives, in separate spaces, so I began the journey of blending them together unapologetically. This course represented my life, my state of mind, and my future career in STEM.”

To Babb, analyzing racial bias in STEM is a step forward and one she continues to practice. “I attribute the majority of the inequity to socioeconomic phenomena that is rooted in the inequities of our educational system,” said Babb. Like Riley and White, Babb leaned on mentorship for success during her time at Barnard. “I now make the effort to mentor budding BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] scientists,” Babb said, highlighting STEMNoire as one such group for continued mentorship. She also put together a University of Maine event to discuss the impact of Black studies in 21st-century higher education, which can be viewed on YouTube.

In addition to courses like Chemistry and Racism, Babb hopes to see Barnard offer its own engineering program or at least amplify promotion of the existing 4+1 Pathway program — which allows admitted students to receive a bachelor’s degree and a master’s in engineering in five years — in its introductory courses. “We need more opportunities for Barnard students to be in spaces that are historically cis male and white so that we may make our mark on the world,” she said.

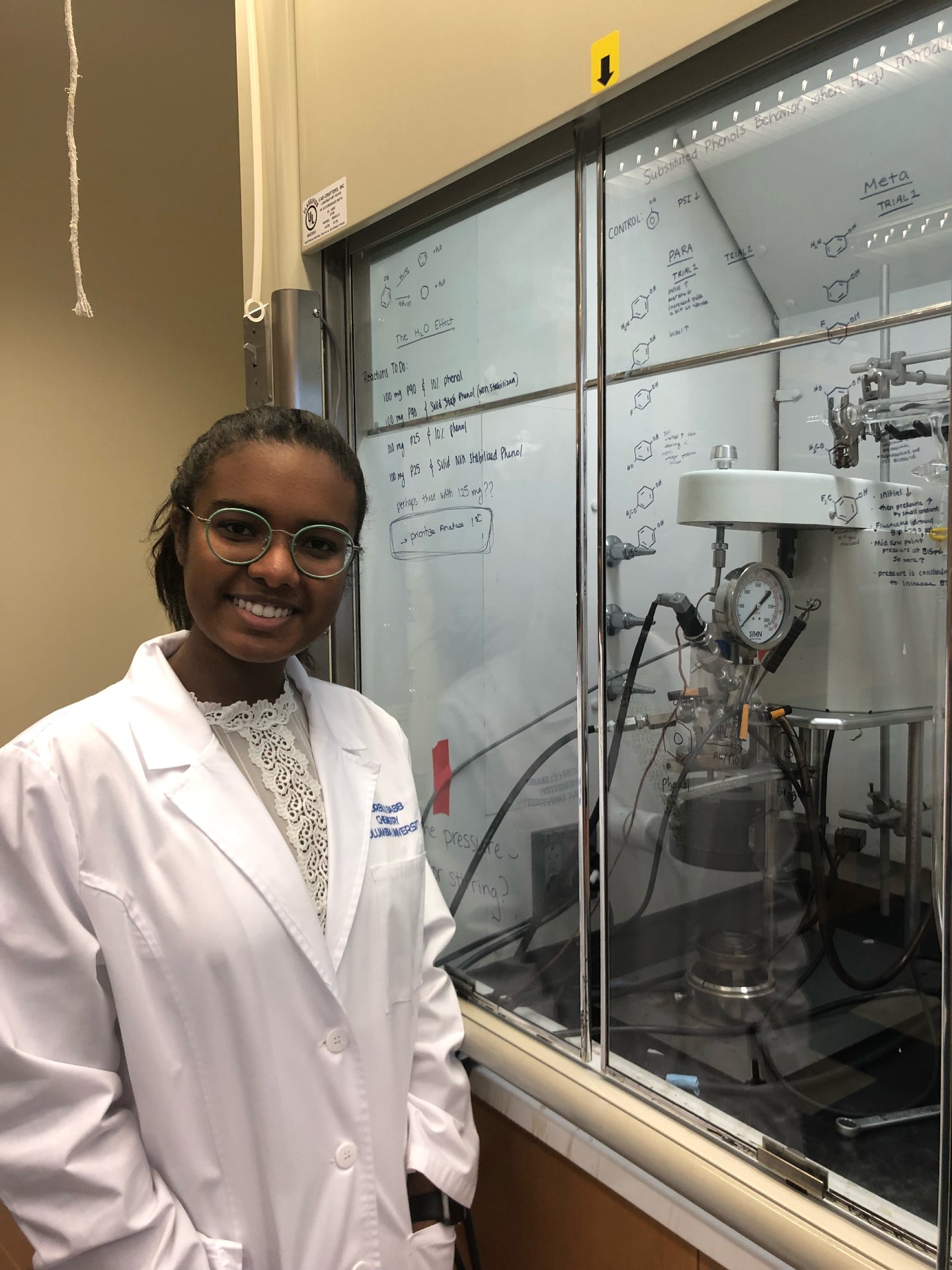

Christina Juste ’22 also benefited from some of these existing opportunities. She was a double major in neuroscience and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies — with a minor in race and ethnicity studies and a concentration in feminist intersectional science and technology studies — and described being a STEM major at Barnard as “so exhilarating and so powerful.” Yet, it hasn’t been perfect.

The competitive environment in some majors, and being the only Black student in some of her classes, had its challenges, emphasized Juste. But after taking the course Chemical Research Methods, Juste felt she had all the tools necessary to participate in Barnard’s Summer Research Institute (SRI), to team up with professors like Austin to conduct lab research. “I’m thankful that Barnard has been really great at giving me the tools to figure out that I like research and that it’s something I want to pursue and then being able to actually pursue those things,” Juste said.

“We will not see more Black women in STEM fields until fundamental changes are made in how we educate and train students, and in the ways in which we mentor and support all faculty [...] so that the climate these women step into is not just supportive but anti-racist.”

Barnard Programs

Beyond Austin and Babb’s course, Barnard has taken some steps to address the need to diversify STEM fields and support women — and especially women of color — once they enter those roles. In addition to broader programs like Barnard Bound and QuestBridge, which seek to connect low-income students and students of color with higher education opportunities, Barnard offers several programs specifically targeted to low-income students from Black, Native American, and Latinx backgrounds who are interested in STEM, such as:

- The Collegiate Science and Technology Entry Program (CSTEP), a New York State program that provides services that increase recruitment, retention, and placement of eligible students in CSTEP-targeted fields and the licensed professions.

- The Science Pathways Scholars Program, or (SP)², Barnard’s own version of CSTEP. This highly selective four-year program — which was featured in Barnard Magazine’s Spring 2020 issue — supports young women from Black, Native American, and Latinx backgrounds or first-generation college students who convey strong interests in biology, chemistry, environmental science, physics and astronomy, or neuroscience. (SP)² students develop strong connections with their cohort while also having access to faculty mentorship, tailored summer programs, networking activities, and guaranteed research funding.

“(SP)²’s success emerges from the intersection of the thoughtful attention and support that the College provides and the eagerness with which these exceptional students seek and embrace opportunities to further their study of STEM,” said Paul Hertz, Claire Tow Professor of Biology and (SP)² director. “Since its first round of admissions five years ago, the number of applicants has skyrocketed.” More proof that with encouraged and supported opportunities, equity in STEM can be achieved.

“[We know that] participation in scientific research and forming a bond with a supportive mentor can increase retention in science,” added Austin. “These programs can make a difference if they are coupled with an acknowledgement that systemic racism is embedded in academia and in STEM fields, and with a desire to change.”

To create meaningful change, the support needs to go beyond admitting talented students. “It’s vital in an increasingly technical world that we’re bringing all voices to the table, and that work has to start long before the hiring process,” said President Sian Leah Beilock. “At Barnard, we know that it is not enough to simply strive for a diverse student body — programs like Access Barnard and SRI work to ensure that all students receive the support that they need to fully pursue academic and career success. There is much progress left to be made, but I am heartened by the initiatives already in place on campus and by the commitment of our community to holding each other accountable.”

The College’s SRI program, launched in 2014, embodies this commitment by introducing a growing number of young women to STEM every year. “SRI has become a key feature of many students’ research endeavors here at Barnard. It fills a critical need in students’ lives by providing them programmatic training and payment for their time, so they can develop the hands-on research skills that are key to entering into advanced degree programs and obtaining jobs in scientific fields post-graduation,” said Koleen McCrink, co-director of SRI and associate professor of psychology. “STEM fields have traditionally had training practices based on connections, and these connections are ripe for stereotyping and exclusion of young women — especially young Black women. SRI helps all students make an early name for themselves in the research community and gives everyone a chance to shine on their own merits, irrespective of stereotypes or considerations of whether the work is paid, both of which may result in students forgoing research experiences during these valuable summer months.”

Progress at Barnard also includes the Faculty Opportunity Hiring Initiative, launched in 2018 to identify, attract, and hire faculty of color, with the goal of moving toward achieving real, structural change in academia as a whole. The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship (MMUF), part of a national program, supports students of color in pursuit of a Ph.D. and a subsequent career in higher education across disciplines. A 2020 Barnard Bold Conference, led by students with support from the Center for Engaged Pedagogy, addressed the theme “Fostering a Culture of Care, Challenge, and Equity.”

This multilevel, institutional approach is key. “It isn’t just about numbers or simply a matter of representation, although that matters — seeing is believing for students; they crave role models,” explained Monica Miller, professor of English and Africana studies and Barnard’s Dean of Faculty Diversity and Development. “We will not see more Black women in STEM fields until fundamental changes are made in how we educate and train students, and in the ways in which we mentor and support all faculty — not just Black women faculty who might be the only faculty member of color or woman, but all faculty, so that the climate these women step into is not just supportive but anti-racist. This work has been ongoing in the academy and at Barnard, but there is so much more work to do.”