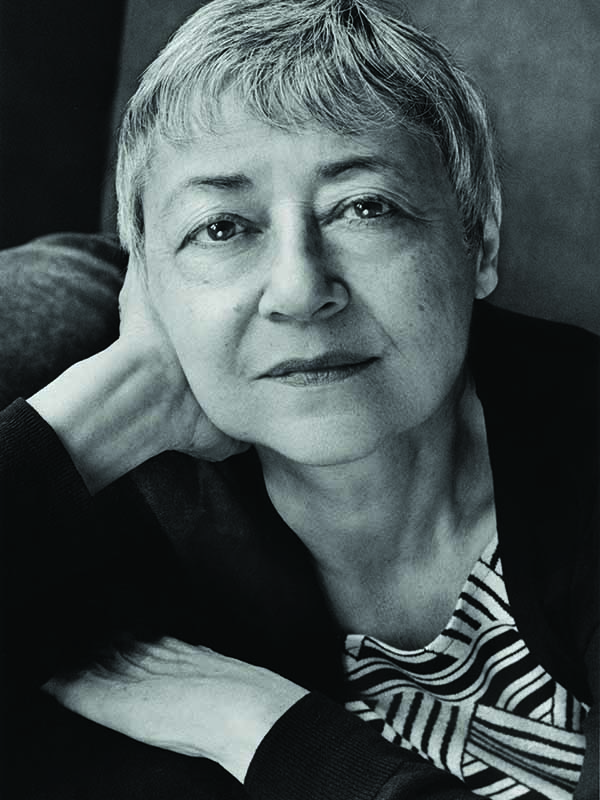

In 2018, Sigrid Nunez ’72 published her seventh novel, The Friend, catapulting her from esteemed literary writer to National Book Award winner and international bestseller — in her 60s.

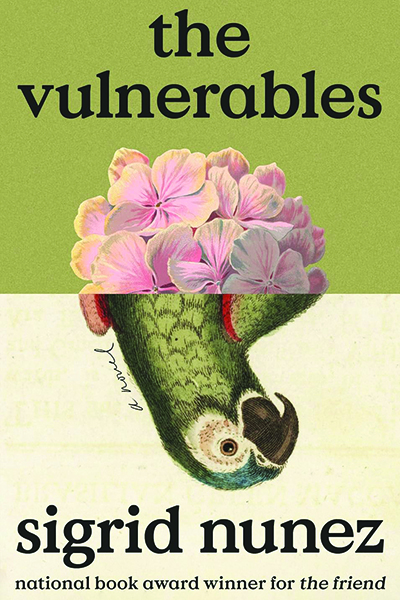

She is currently promoting her latest, The Vulnerables (2023), as the movie version of The Friend, starring Naomi Watts and a dog named Bing, is in production. Along with What Are You Going Through (2020), the three novels are connected by the intimacy of the narrator’s voice and her crackling sensibility: a New York writer confronting external dilemmas — often involving an animal that needs care — while plumbing her rich inner life. The narrator ricochets from literary insights and anecdotes to finely wrought memories and trenchant observations about writing, love, and loss, wickedly funny one minute and heart-stopping the next.

In 2006, I reviewed her Barnard-inspired novel, The Last of Her Kind, for The New York Times, and we met soon after. Her contribution to my 2009 anthology, Mentors, Muses & Monsters: 30 Writers on the People Who Changed Their Lives, inspired her 2011 memoir, Sempre Susan, about the celebrated writer and critic Susan Sontag.

Sigrid and I recently conducted an interview about writing, teaching, and a Barnard professor who influenced both of us.

Elizabeth Benedict: We both studied with Elizabeth Hardwick at Barnard. What were her most valuable lessons to you? What are your lessons to students?

Sigrid Nunez: Hardwick’s most valuable lessons to me came not from taking class with her but from reading her work: the beautiful sentences, the incisive criticism, the virtuosic gift of observation. Since she believed that writing cannot be taught, she put disappointingly little effort into discussing our manuscripts, but I found her passion for literature and the life of the mind inspiring. I was also grateful to learn from her never to be satisfied with any writing that hasn’t gone through multiple drafts. As a teacher, I’ve tried to pass that same lesson on to my students as well as to convince them that they’ll learn far more from reading other writers than from any workshop and that they should read as much as possible.

I think what can be taught about writing is largely editorial. You try to show what works and what doesn’t work in a story, and why. You try to teach students the difference between a good sentence and a bad sentence. You want them to see that the way a person writes is as important as whatever they may write about. But you don’t tell them what they should write about; that has to come from them.

EB: I love The Vulnerables. Broadly, it’s about a writer who goes on long walks every day during the pandemic, attends a funeral, and takes care of a pet macaw. Like the narrators in the other recent novels, she reminds me of you. Yet even with all these similarities, it’s a novel. What makes it a novel?

SN: The Vulnerables is an invented prose narrative of book length that deals with imaginary characters and events. This fits the definition of a novel. It is true that the book contains some material that is not fictional, also that there are strong similarities between the narrator and the author. But this does not make the book either a memoir or a work of autofiction. Most of my writing falls outside traditional categories. But the house of fiction has many rooms, and there is more than one kind of novel.

EB: What compels you to write?

SN: Writing is something I’ve always wanted to do, something that, in spite of being often frustratingly difficult, comes naturally to me and gives me enormous pleasure. When I’m writing, I feel like I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing, and I never feel estranged from myself, as I can sometimes feel when I’m engaged in some other activity. Also, there is a certain kind of thinking that happens only when you’re struggling to put things into words. The thinking that I have to do when writing helps me to understand many things — about myself, my life, my past, as well as about other people and life in general.

EB: What’s life like between books for you? Are you yearning for time to begin your next project?

SN: In the past, it usually hasn’t taken me long, once I’ve finished a book, to begin a new one. But this time it’s been different. That’s because, with The Vulnerables, I found myself writing the final volume of what has turned out to be a kind of trilogy — though I never planned for it to happen that way. What Are You Going Through came out of The Friend and The Vulnerables came out of What Are You Going Through. I’m not inspired to make it a tetralogy, though, and at the moment I have no idea what kind of book I want to write next.

EB: Your early ambition was to be a dancer, and you didn’t begin publishing books until you were 44. What wisdom or reassurance can you offer writers whose work isn’t yet being recognized or published?

SN: I could never honestly reassure a struggling writer that, if they just keep at it, publication or recognition will come. Because that simply is not true. I kept writing because I really wanted to, not because I believed it would all turn out well in the end. It could just as easily have not turned out well. Literary success is so unpredictable, dependent on so many forces outside the writer’s control. What keeps you writing has to be more than the hope of worldly reward. The practice itself has to do something for you, something important and valuable.

Elizabeth Benedict ’76 is the author of five novels and the recent memoir Rewriting Illness: A View of My Own. Her anthology, Me, My Hair, and I: Twenty-seven Women Untangle an Obsession, was selected for the Barnard Book Award for several years.