Barnard Trustee Frances Sadler ’72 insists that in college she was not the type of person to start an organization. She never ran for office in a campus group. “I wasn’t that kind of student,” she says.

But as luck or maybe fate would have it, during the 1968-69 school year, Sadler was living with her friend Elaine Johnson ’72 in one of the largest dorm rooms of any black students on campus. Naturally, their room became the de facto place for black students to meet, not just to study, but also to explore what they were experiencing. To incubate what, in a matter of months, would become the Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters (BOSS), a group that celebrates the 50th anniversary of its first official act this February. From its start, the group has maintained just a single membership requirement: If you are black at Barnard, you are in. (In its early years, before Latina students formed their own group, many were involved in BOSS as well.)

As it has for half a century, today BOSS maintains a three-part agenda. It works to make Barnard the institution accountable to the College’s stated goal of inclusion and empowerment for all women. On a campus where only 9 percent of the student population identifies as black or African American, BOSS helps affirm their choices and possibilities. (African American women make up just 8 percent of college students nationwide but 15 percent of college-aged Americans.) The group also serves as a safe space for students who often feel isolated or exposed to racist affronts, whether at the College or from society at large, which often denigrates both their intelligence and potential. Sometimes, being a black woman at Barnard can be difficult, says Alicia Simba ’19, BOSS’s current president. Occasionally, she says, it feels like “we are not supposed to be at Barnard. BOSS lets you know we have been at Barnard for over 50 years.”

The history of black women at Barnard

Founded in 1889, the College waited a full 36 years before enrolling its first African American student, the already acclaimed author Zora Neale Hurston ’28, whose admission was championed by Barnard founder Annie Nathan Meyer. By the mid-’50s, African Americans were still not well-represented, with only two students per class year. Their experiences were difficult. One alumna who left the College as a junior in 1954 and never returned later told the Barnard Bulletin, “I just couldn’t make the connection between Barnard and my reality as a black woman — I had to leave.”

By the fall of 1968, in the midst of the civil rights, women’s, and anti-war movements, numbers finally reached a critical mass, with approximately 80 black students living on campus and off. They wanted to amplify their voices to change the sobering reality they faced: At the time, Barnard had no black professors; black experiences were not integrated into the curriculum; syllabi failed to contain works by African American authors and academics; and at the College’s gates and in its residence halls, students and their guests regularly faced harassment from campus security.

“We were a source of support for each other and also a resource for the school when it came to understanding and engaging black women on campus.”

- Tesha McCord Poe ’94

Across the street at Columbia, students from both sides of Broadway protested these and other conditions in the spring of 1968 by occupying Hamilton Hall. (To read more about the ’68 protests, see our Spring 2018 issue.)

Then, in the ’68-’69 school year, “the men at Columbia took over Hamilton Hall in a second protest with pretty similar demands [to the first one],” remembers Leslie Hill ’72, now an associate professor of politics at Bates College, in Lewiston, Maine. “The women — we were trying to figure out how to support the men.”

That support included attending meetings of the Students’ Afro-American Society (SAS) at the still all-male college. “I would go to every meeting,” Sadler says. But women’s options for SAS participation were limited. “It was about making coffee and copies! I didn’t go to college for that,” Sadler recalls. She and her friends decided to not return to the meetings.

Things were not much better on the west side of Broadway, though. Hill remembers there was “a lot of insensitivity from [white] faculty and students. And then, of course, there’s this vibrant social movement going on outside. We’re thinking, ‘So where are we seeing ourselves reflected at Barnard?’ And saying, ‘We need to come together and just provide community for each other.’”

The Manifesto

One of the very first things that the newly formed BOSS did was tell Barnard’s administration what it needed. In February 1969, in the manner of the day, the group sent a manifesto to then-President Martha Peterson. The document, which went on to receive national attention, argued for an interdepartmental major in Afro-American studies; a voluntary, separate living space for black students; black professors; courses that were relevant to African American experiences; improved financial aid; increased recruitment of black students; soul food in the dining room; and an end to harassment by campus security guards.

Although the Columbia Spectator, the Columbia student newspaper, reported that the demands were supported by nearly all of Barnard’s black students, the group faced a standoff with the College’s administration. President Peterson initially said at a faculty meeting that she hoped the faculty and administration would recognize they’d been “remiss” toward black students, and that she considered the demands “reasonable.” Yet in her formal response, issued a week later, Peterson did not grant BOSS the sole power to implement its demands, a central component of the manifesto. The organization rejected her response and held a series of meetings to explain its position. “Our demand for the power to have control over our environment is an extension of the movement of blacks throughout this nation towards self-determination,” the group wrote in the Barnard Bulletin.

As students argued with the administration over their demands, the College created a lounge for them in 121 Reid Hall. But students wanted more than a “Black room,” as they sometimes called it. They also wanted a dedicated black floor in one of the dorms. In 1969, the Barnard housing office established 7 Brooks, the name given to the seventh floor of Brooks Hall, as a dedicated space where black women could choose to live. “If it hadn’t been for 7 Brooks, I don’t think I could have made it through Barnard,” alumna Marian Coleman '74 told The New York Times, echoing other students’ belief that it was a welcome space away from the attitudes encountered on campus.

There were other successes, too. That same year, the school announced the appointment of three black faculty members while the Admissions Office began a dedicated effort to recruit black students.

Over the course of 50 years, as the group and the College have worked to realize many of the initial demands, there have been setbacks as well as gains. In 1974, the school had to eliminate 7 Brooks after losing a two-year dispute with the New York State Board of Regents, which said it promoted voluntary segregation. Creating the Africana Studies took more than 20 years; the major was not established until 2014.

In 1987, in a draft of a letter, group members wrote: “Barnard presented itself as a place that encouraged diversity [and] critical thinking and which actively sought its students from a wide variety of backgrounds. ... But Barnard has not proven to be such a place.”

Promoting from within

In recent years, conditions at the College have improved significantly, even if BOSS’s original dream has yet to be fulfilled. And some of that progress is due to the key roles African American administrators have played. First among them was Lemoine Callender, who served as the assistant to the dean of faculty and was then one of only two black administrators on campus in 1969. Hill describes her as a mentor and “a champion for us individually and collectively.” Callender’s was a symbiotic relationship with BOSS. “Our presence gave her an opportunity to open up conversations with the administration that she might not have been able to have,” says Hill. “And she helped us translate for the administration what we wanted.”

In 1984, Dean Vivian Taylor took over the unofficial role Callender once held. Taylor joined Barnard as director of the College’s Opportunity Programs that help low-income students and students of color. She later became an associate dean of the college, dean for multicultural affairs, and vice president for community development, before leaving Barnard in 2012. In her professional role, she provided support to BOSS — both as an organization and, individually, to members.

Says Taylor, who is now associate dean for diversity and cultural affairs at the Columbia University School of Nursing, “I felt that it was critical for BOSS and black students to know that someone who looked like them in administrative leadership at the College understood their plight and was there to lift them up and let them know they were not alone. It was important to let them know that they belonged at Barnard and, like all Barnard women, would be making an incredibly positive difference in our world. It was also important to let them know that others in the Barnard administration who didn’t look like them were also rooting for their success.”

Simba describes the group’s interactions today with black administrators as very personal and one-on-one. Former Dean of the College Avis Hinkson ’84, as well as current Deans Nikki Youngblood Giles and Jemima Gedeon, are just some with whom she says the group has a very “support-based” relationships.

The Celebration of Black Womanhood

The inaugural BOSS members did not just leave behind a set of demands when they were graduated in 1972. They also left the school with a still-honored tradition, the now-weeklong Celebration of Black Womanhood. Originally called The Black Women’s Conference, the event is an opportunity to invite black women from the arts and a range of professions to come to campus. The first one, in 1972, featured poet Sonia Sanchez and author Toni Cade Bambara. “At that time,” says Hill, “one couldn’t speak of anything that amounted to [collected] black women’s history. So we were all bringing [ideas to shape the event] that we had found in our families, in our communities, in our churches.”

The Black Women’s Conference became the Celebration of Black Womanhood, and expanded from a full day to a week. Actor and activist Ruby Dee, Planned Parenthood President Faye Wattleton, and lawyer-activist Florynce Kennedy are just some of the speakers who have attended.

A lifeline for students and alumnae

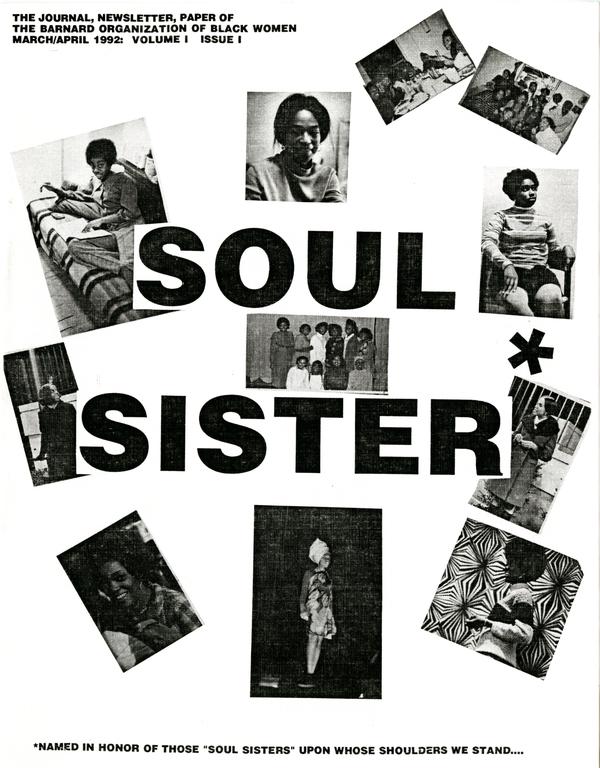

As the organization developed over the years, its name has reflected changes in ideas and language. In 1974, BOSS became Barnard Organization of Black Women (BOBW). In 1995, the group changed its name again, to the Black Sisters of Barnard and Columbia (BSBC). What did not change was the group’s purpose. “We were a source of support for each other,” says Tesha McCord Poe ’94, “and also a resource for the school when it came to understanding and engaging black women on campus.”

Asali Solomon ’95 agrees. “You absolutely need to be able to seek out other black women in white institutions,” she says about the necessity of the organization. In BOBW, Solomon “met interesting black women from all over the country, with interesting hair and ideas.” Awo Ansu ’87, a political science major, tells a story about a BOBW classmate — a computer-science ace — who helped her pass a computer-science class Ansu felt she had “no business being in.”

“She stayed with me in the computer science lab until two, three in the morning, helping me.” Why? “Because we’re going to pass this class,” Ansu’s friend said. Because, as BOSS women over the last 50 years have reinforced, supporting and helping each other succeed is one of their most important goals. Notes Sadler, “there was a crew of us…[and for] every important decision that I ever made in my life, one of them was there.”

Back to BOSS

Elvita Dominique ’03 joined what was then known as the BSBC for the same reasons her predecessors had. One night, in 2002, she was in the meeting space, by then christened the Zora Neale Hurston Lounge. “I was just flipping through some of the files. And then I started finding references to BOSS. And I was like, ‘Wait a second. This used to be called BOSS? Why isn’t it called BOSS now?’”

Dominique, the group’s president, brought the name to its officers and asked, “‘Shouldn’t we go back to our origins?’ I didn’t know [the organization] was that old, that there was this whole history.”

Dominique not only renamed the group, but she wrote her senior thesis on black women at Barnard, so that it would be easier for others to know their stories. “The women who went before really paved the way for me to even have an experience at Barnard,” she says. “They left this positive legacy.”

Under Dominique’s leadership, BOSS also entered into some of the more traditionally feminist spaces of Barnard. At Take Back the Night, the annual anti-sexual violence march, “there was no banner under which minority women could walk together to say, ‘This happens to me, too,’” she recalls. “And I thought, ‘We’re going to have a big banner. And we’re going to go out there and say we also support this. This is also our issue.’”

A half century

Five decades after it presented its initial demands, the BOSS of 2019 is in many ways similar to the BOSS of 1969. Discussions in the lounge may be about hip-hop instead of soul, but beyond the changes in pop culture, the mission remains the same: support and progress. “We now have a mentor program between [classes],” adds Simba, who is an international student from Tanzania. “The benefit of BOSS is that you get to meet new people, but [especially those] who specifically are going through at least some of the same issues as you” — issues that have improved dramatically but have in no way disappeared.

Indeed, at an October dinner celebrating the anniversary of the organization that began in her dorm room, Sadler told a room full of BOSS members, present and past, “It is important that the goals of BOSS really are the same [50 years later]... to find us a place where we can figure out who we are, and be who we are. And grow into the women that we’re meant to be.” •

Ayana Byrd ’95 is a Brooklyn-based author who met some of her best friends through BOBW, as BOSS was once known.