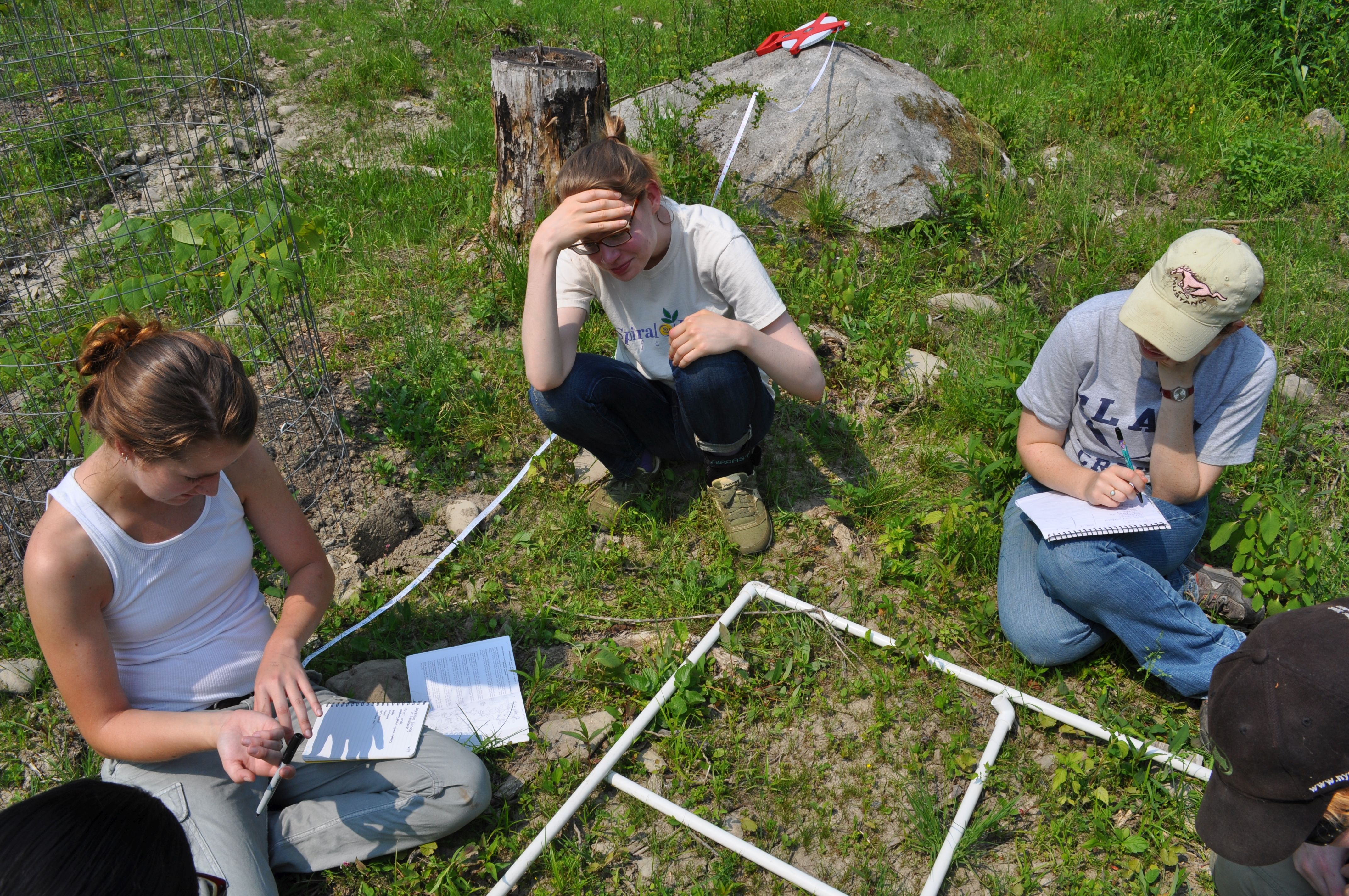

[Main photo: Professor Maenza-Gmelch at Black Rock Forest]

Senior lecturer in environmental science Terryanne Maenza-Gmelch has guided Barnard students through the process of forest ecology since joining the faculty in 2006. At the Black Rock Forest Consortium, where she developed and teaches summer field programs, Maenza-Gmelch offers students from middle through graduate school hands-on research opportunities to reflect on past environments, ecologies, and more.

A 2021 recipient of the College’s Teaching Excellence Award, Maenza-Gmelch has a passion for educating students on the environment that's evident in the courses she curates (in 2016, she took her Intro to Environmental Science students aboard the research vessel Seawolf to conduct research on the Hudson River) and in the web resources she’s produced, like the Paleoecology Module for the Virtual Forest Initiative — established in collaboration with Columbia’s Center for New Media Teaching and Learning to offer students a simulated experience when learning about a forest’s ecosystem.

With STEAM in the City, Barnard’s new initiative with the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF), Maenza-Gmelch mentored K-8 educators in the Harlem and Morningside Heights neighborhoods on building a science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) curriculum that uses the City’s parks and public spaces as learning sites. To learn more about the City’s treescapes during Climate Week NYC (September 20-26), we spoke to Maenza-Gmelch for a “5 Questions With …” interview on the many ways that trees protect the environment.

What are some of NYC’s native trees and how do they protect the city?

I would like to make the distinction that NYC has street trees that are monitored separately from trees in parks. Parks have planted trees, as well as areas called “Forever Wild.” Some of the most common street trees in NYC are London planetree, Norway maple, and ginkgo. Those three are not native. On the other hand, 82% of canopy trees in NYC forests are native. The most common native trees in these urban forests are sweet gum, red oak, red maple, and black cherry, among others.

Whether the tree is on the street or in the park, each provides the same ecosystem services to humans. Trees sequester carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and help mitigate climate change. Trees also cool the local environment through shading; heat is absorbed during evaporation of water from the surface of leaves and from within the leaf’s interior. Trees also provide a pleasant aesthetic that contributes to our well-being. Trees clean the air by trapping particulate matter and absorbing pollutants like ozone. One more important service that trees provide is stormwater reduction. The roots capture water and therefore reduce the volume that would flow to wastewater treatment plants during storms. In this way, more trees in the watershed keep the Hudson River cleaner. So you can see that trees are beneficial and protect the City and its residents.

An unfortunate fact, and an issue that must be remedied fast, is the disparity in the number of trees found in low-income and high-income neighborhoods — there are fewer trees in low-income neighborhoods. The tree abundance disparity leads to temperature disparity, [making] it much hotter in the neighborhoods with fewer trees. More trees need to be planted in these areas.

As NYC’s climate changes, have you observed any differences in its trees or the organisms that live on them that should concern us?

The temperature and humidity changes that come with climate change can certainly stress trees. Drought, for example, weakens the trees. People can help the trees in their neighborhood by watering them during dry periods. When trees are weakened by drought and heat, they become more susceptible to disease and attacks from invasive pests. As one example, currently the spotted lanternfly poses a threat. They attack trees by piercing the soft tissues and extracting the sugar-rich fluids, [which] dries the tree out.

An unfortunate fact, and an issue that must be remedied fast, is the disparity in the number of trees found in low-income and high-income neighborhoods — there are fewer trees in low-income neighborhoods.

How do students use the Black Rock Forest Consortium and urban parks in research?

In the Environmental Science Department here at Barnard, we get students into the field to work with trees in several ways. We start with tree identification in Riverside Park and observe how trees support biodiversity. Eventually, students measure the tree diameters on campus so we can calculate how much carbon dioxide our campus trees have sequestered to date. Trees are an excellent subject to use to get acquainted with ecology. For example, in STEAM in the City, a program Barnard has with local schools in Harlem, I trained teachers in mapping, identifying, and measuring trees so that they can use the parks — such as Morningside Park or even the street trees in front of their school buildings — as a place for their class lessons.

As far as studying trees goes, Barnard also has a membership to an outstanding field station called Black Rock Forest. It is one hour north of NYC in Cornwall, N.Y. This 4,000-acre, biologically rich, eastern deciduous forest offers many opportunities for students to explore the ecology in an undisturbed setting, as a contrast to the urban forests of NYC. Students, in addition to faculty, do research there. Many students over the decades have done their senior thesis research at Black Rock. They have studied a broad range of topics, from turtle ecology to bird diversity, in relation to habitats and carbon storage in the long-term tree plots.

What role can trees play in saving us from ourselves?

The climate report that came out in August 2021 gives us the most recent consensus on the science behind climate change. The global climate is getting warmer. It is 1.1 degrees Celsius warmer than the preindustrial global mean surface temperature baseline. Humans are causing climate change through greenhouse gas emissions. There has to be, and are, multiple ways to combat climate change. Healthy forests are a tool. Forests sequester carbon during photosynthesis. So, forests must be protected, and damaged forests must be replanted. We need as many trees as possible. The environmental science lab students at Barnard measure the campus trees each November and quantify how much carbon dioxide they remove from the atmosphere. Each person can contribute by planting and caring for a tree.

Whether we are scholars or out for a stroll, what should we know about city parks?

If each person learned to recognize at least one tree species in their park, learned its name, and had an increased awareness about trees, they would find themselves tuning in to nature more often. Observations that people can make in parks — like tree damage or tree health, bird abundance or absence, flowers and pollinators — would be a window into NYC’s environment. The next step might be environmental stewardship. NYC parks are a great place to find some peace and quiet and reflect on the nature in them. Research being done at Barnard and Columbia shows that people benefit from NYC green spaces, especially during the pandemic.

Barnard’s Stats and Facts:

- 10% of courses are sustainability related or focused

- Campus carbon intensity has been reduced by 35% since 2005

- 21 departments across campus engage in sustainability or climate research

- The College has organics collection bins in 30 offices, 5 academic buildings, and 3 dorms

- 7 academic departments or programs offer majors, tracks, or concentrations in climate, sustainability, and environmental justice