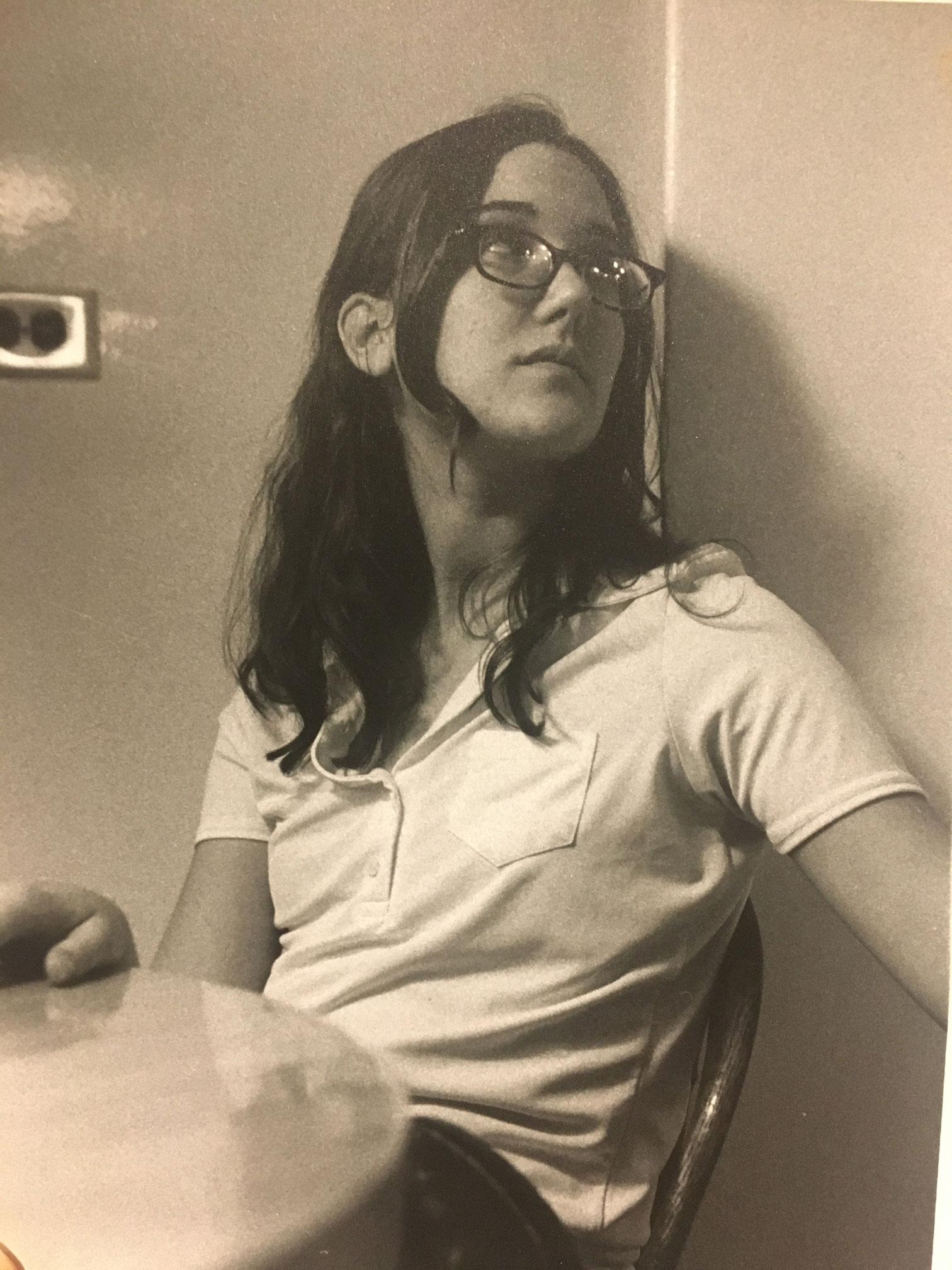

Erin L. Thompson ’02 is an art historian like no other: She’s the nation’s only full-time professor of art crime. “My favorite place to be in New York has always been the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” she said. “Not that my love keeps me from criticizing them for acquiring potentially looted antiquities.”

From her first semester at Barnard, Thompson knew that art history was her calling and promptly enrolled in courses to prepare for her next step. “I went directly into the Ph.D. program in art history at Columbia after I graduated from Barnard,” said the art history and philosophy major.

While writing her dissertation, Thompson’s artifactual interests grew into a study of how art got into museums in the first place. Passionate about archeological looting and the smuggling of antiquities to supply the market, Thompson pursued a J.D. from Columbia Law School — while earning a Ph.D. — “to try to fight this destruction of the past,” she said. After completing both programs in 2010, she worked as a corporate lawyer and for New York City’s Conflicts of Interest Board for over three years, researching and writing about art law on the side. In 2013, Thompson saw a job posting for a professor of art crime, fraud, and forensics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY) and jumped at the opportunity. She has been there ever since.

Her upcoming book, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America’s Public Monuments (February 2022), focuses on monuments. In light of the recent removal of the Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson Confederate statues — the city’s 2017 vote to remove Robert E. Lee’s sparked August’s deadly Unite the Right rally there — we turned to Thompson for “5 Questions With …” to learn how she became an expert on deliberate art destruction.

How did you become the nation’s only full-time professor to teach art crime?

I began my career by researching the use of international treaties and national laws to protect antiquities from looting and smuggling, but I’ve come to understand what I do more broadly. Art and law might not seem to have much in common with one another, but I’ve found that examining areas of overlap between them can reveal new things about them that we hadn’t even suspected we weren’t understanding.

For instance, a lawyer who represents men detained at the Guantánamo Bay military prison camp contacted me to ask if I would look at the art made by her clients. My first response was intense surprise — What did she mean that detainees were painting landscapes? — which then led me to realize I didn’t really understand who these men were. So I curated an exhibition of their art to help other people question their assumptions, too. (See the slideshow below.)

Watch Thompson’s 2018 TEDx talk on Guantánamo art below:

What “art crime” has had the most impact on you?

I grew up in Arizona, and I was not prepared for my first New York winter! I spent a lot of it in the warmest place I could find — the basement of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia. Browsing books, I found one about Palmyra, an ancient Roman city in Syria. Palmyra’s architecture and sculptures were such beautiful examples of the ancient art I was discovering in my art history classes, and they were in the middle of a desert that looked like home.

I loved Palmyra’s temples of Bel and Baal Shamin, built in the first and second centuries CE from dusty, pinky-orange limestone that looked like it was reflecting the light of sunset. These were among the best-preserved buildings from the ancient world until 2015, when members of the Islamic State detonated oil containers packed with explosives and destroyed them. This destruction changed my career. There was a worldwide reaction; it wasn’t just me in the library basement who cared about antiquities. Now I work with experts and communities from around the world, including Syria, to help people preserve what is most important to them.

What were some of your favorite courses while at Barnard?

My first-year seminar was on the topic of being creative when you’re faced with constraints. Our professor insisted that what seemed like limitations could really be inspirations to think of new ways to do something. I took this to heart, as I often have to invent ways to study topics like art forgery, where there is no established methodology.

My classes at Barnard taught me that there’s always something new to discover and that one of the best ways to get there is by questioning something people take for granted. Now, whenever I see lots of people assuming something is true, I zero in on that assumption. For example, recently I’ve been arguing against the commonly held idea that adding contextualizing signage can stop a public monument from spreading a harmful message.

Why did you want to write about the rise and fall of controversial U.S. monuments?

As an art historian, I knew that toppling monuments happened throughout history when communities decided that they no longer wanted to honor or obey the represented person or idea. I wanted to write this book to show that what has happened in the last few years is part of this history. In fact, the very first bronze statue to be set up in America, a monument honoring King George III, was torn down by New Yorkers after a reading of the newly written Declaration of Independence just a few years later!

The book was also a quest for answers to questions I couldn’t find anyone else asking. I wanted to know what was happening with monuments removed from their bases. I found that most of them have gone back on display elsewhere, which, to me, changes everything; fighting about removal is different than fighting about reshuffling.

So much of the discussion of the protests I was seeing was written by people who assumed they already knew everything there was to know about the motivations of protestors and the history of the monuments. I decided I would stay curious, interviewing people and digging into history to let the opponents and defenders of the monuments speak for themselves. I found amazing, untold stories, like that of unpaid prisoners forced to complete the world’s largest Confederate monument. I am honored to bring these stories the attention they need and deserve, if we as a nation are to have all the information we need to make decisions about our public monuments.

How has the nation’s cultural mood regarding Confederate monuments shifted since 2017’s Unite the Right rally?

In 1876, Frederick Douglass pointed out that a newly dedicated memorial to Lincoln demeaned Black Americans. The artist showed a Black man as a second-class citizen, passively receiving emancipation as a gift from Lincoln, instead of showing the truth — that enslaved people had fought hard for their own freedom. It took almost 150 years for many Americans to catch up to Douglass, but the deadly clashes in Charlottesville over a monument to Robert E. Lee made it undeniably clear that our public monuments make arguments about what kind of people should be in power and what kind of people should remain silent.

In the summer of 2020, when protests began after the death of George Floyd, activists immediately drew attention to the way that public monuments enshrined the type of discrimination and erasure they were protesting. More than a hundred public monuments were subsequently removed from their pedestals.

More and more Americans agree that our public monuments do not represent our diverse nation and often celebrate those who fought hard to deprive people of their rights, education, or even their freedom. My research has also revealed an opposing trend: Many legislators are scrambling to put new laws into place to prevent communities from making their own decisions about monuments. We’re at a crossroads between change and repression. I encourage Barnard community members to make their voices heard in these debates in their own neighborhoods.