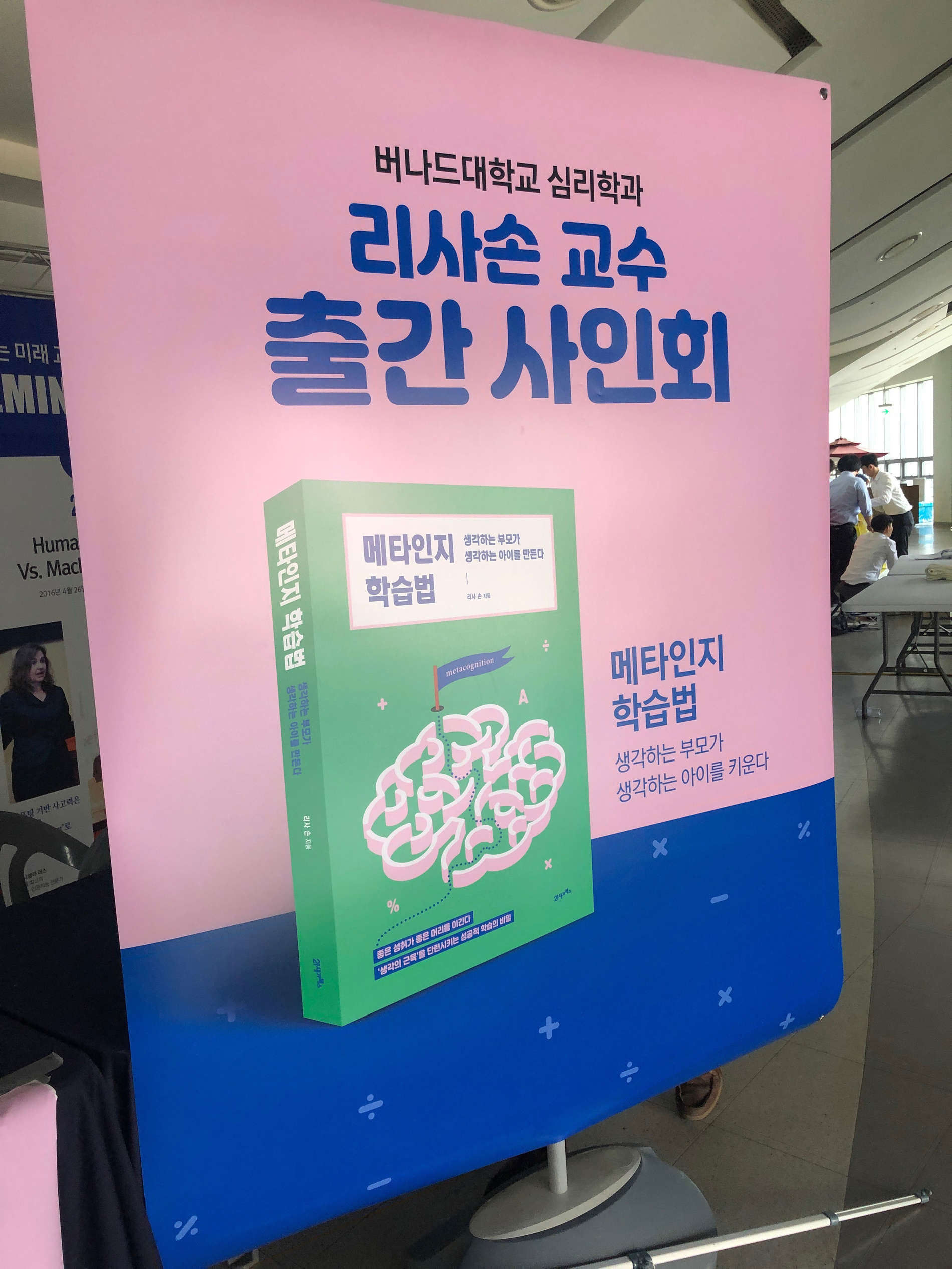

Associate professor of psychology Lisa Son, who specializes in human learning, memory, and metacognition, practiced what she teaches when she wrote and published her new book, Metacognition: The Thinking Parent Makes the Thinking Child (June 26, 2019), entirely in Korean, all while living in South Korea on a fellowship from September 2018 to June 2019. Twice named a Fulbright Scholar to the country, Son used her most recent honor, a Fulbright Visiting Professor Award, to examine educational differences between Korea and the United States in an effort to better understand where and why people fail to learn successfully. The first-generation American had impeccable conversational skills. but Korean was not her native language; she did not attend school in Korea and didn’t know how to type in Korean prior to her fellowship.

Associate professor of psychology Lisa Son, who specializes in human learning, memory, and metacognition, practiced what she teaches when she wrote and published her new book, Metacognition: The Thinking Parent Makes the Thinking Child (June 26, 2019), entirely in Korean, all while living in South Korea on a fellowship from September 2018 to June 2019. Twice named a Fulbright Scholar to the country, Son used her most recent honor, a Fulbright Visiting Professor Award, to examine educational differences between Korea and the United States in an effort to better understand where and why people fail to learn successfully. The first-generation American had impeccable conversational skills. but Korean was not her native language; she did not attend school in Korea and didn’t know how to type in Korean prior to her fellowship.

Still, she was interested in exploring the metacognitive world that her parents came from. “I was so happy that my parents could read about my research and the things that are important to me, and for the first time in their native language,” Son said. Metacognition tackles the myths that long-term learning, fast learning, easy learning, and error-free learning are best. In June 2019, Son also published the article “The Irony of Self-Reflection” in Korean, for the Korean version of Skeptic Magazine.

In this back-to-school Break This Down interview, Son introduces her new book and shares the process of writing one in a foreign language while also being far away from home.

What is your book about, and what did you learn from writing it?

My book is about the science of metacognition [how we think about what we think] for the general public. It begins with a definition of metacognition that mimics the ancient Greek maxim “Know thyself” and describes a self-reflective process, like a mirror. However, instead of a reflection of outer appearance, metacognition refers to an internal reflection — we can think about our thoughts, emotions, and other invisible cognitions. A reflection of the external self can show reality, but our metacognition mirror is prone to distortions, illusions, and even lies.

My book is about the science of metacognition [how we think about what we think] for the general public. It begins with a definition of metacognition that mimics the ancient Greek maxim “Know thyself” and describes a self-reflective process, like a mirror. However, instead of a reflection of outer appearance, metacognition refers to an internal reflection — we can think about our thoughts, emotions, and other invisible cognitions. A reflection of the external self can show reality, but our metacognition mirror is prone to distortions, illusions, and even lies.

I divided the first part of the book into “three umbrella illusions”: Fast learning, easy learning, and error-free learning are best. With the parent or teacher in mind, I presented data showing that metacognitive illusions likely occur when the above three learning strategies are being used. For instance, we are likely to believe we know information when the answer is provided to us, when, in fact, that information is likely to be forgotten because we do not resolve the answer on our own. These and other illusions are the basis for hindsight bias, imposter syndrome, and a decrease in self-confidence.

In the last part, I ponder the evolution of metacognition. We all have an ability to self-reflect, but is there a larger reason, beyond academic learning, for why this exists? I reflect on the ways in which making mistakes while learning not only leads to long-term retention but also may provide the basis for courage. I describe times when learners of all ages need to summon courage in different situations, including during study, in the classroom, and in society. I provide personal examples, [from when I was] a young learner in school and as an adult parent of two young children, highlighting mistakes I’ve made, illusions I’ve had, and how I continue to find courage in small and large tasks. Even writing this book, in my nonnative language, took an immense amount of courage. And I learned through the process of writing that for me this was a “metacognitive,” eye-opening process.

What was the inspiration behind writing a book in Korean?

When I received my first Fulbright to South Korea, in 2013-2014, I began comparing metacognitive processes cross-culturally. During that year, I appeared on a Korean TV broadcast to present the concept of metacognition, [including] one of my experiments, which focused on how students from Barnard and Columbia believed they would remember passively read information better than actively tested information. The results showed that testing, not reading, led to better test performance later. This data, and the general conclusion that effortful learning is more effective, was probably the first time many people in Korea heard the term “metacognition.”

For my teaching scholarship, I taught metacognitively guided courses and observed a society-wide interest in metacognition, as well as some illusions. Many parents thought that improving their child’s metacognition meant the child would become a “faster” learner, when metacognition, in fact, encourages the learner to slow down, to be reflective, and to know when they might be wrong — the opposite of what people thought. Given these myths, I wrote the book to spread awareness about the science behind metacognition. But I had never attended schools in Korea, [so] why would anyone listen to what I had to say about education in Korea? On the other hand, I did spend my Fulbright years there, and many summers, meeting students and parents.

I thought it would feel most natural to write the book in Korean from the start, [and] it was an incredible process. There are so many memories and fun mishaps, and as I mentioned above, these errors are the things that make the book wonderful to me. The day I started to write, I realized, while laughing, I really don’t know how to type in Korean. I had typed short notes, but I wasn’t near the speed I needed to be at to finish a book! I spent the first day writing this book on my tiny iPhone. The second day, I thought this was ridiculous, and with some fear, opened my laptop and started typing in Korean at a snail’s pace, pressing wrong letters. After a few weeks, I became faster, and by the end of three months, I could type almost as quickly as I could in English. These obstacles were some of my most cherished memories of the book-writing process. And of course, writing the book in Korean, while serving as a Fulbright ambassador in Korea, made it the most ideal experience.

Was there a preferred place to work or draw inspiration from during the process?

I wrote the entire book while “cafe hopping!” Korea is well known for its cuisine, but some don’t know about the cafe scene. In America, people joke that there’s a Starbucks on every street; in Korea, there are many cafes on every street. Each morning, I chose a different one.

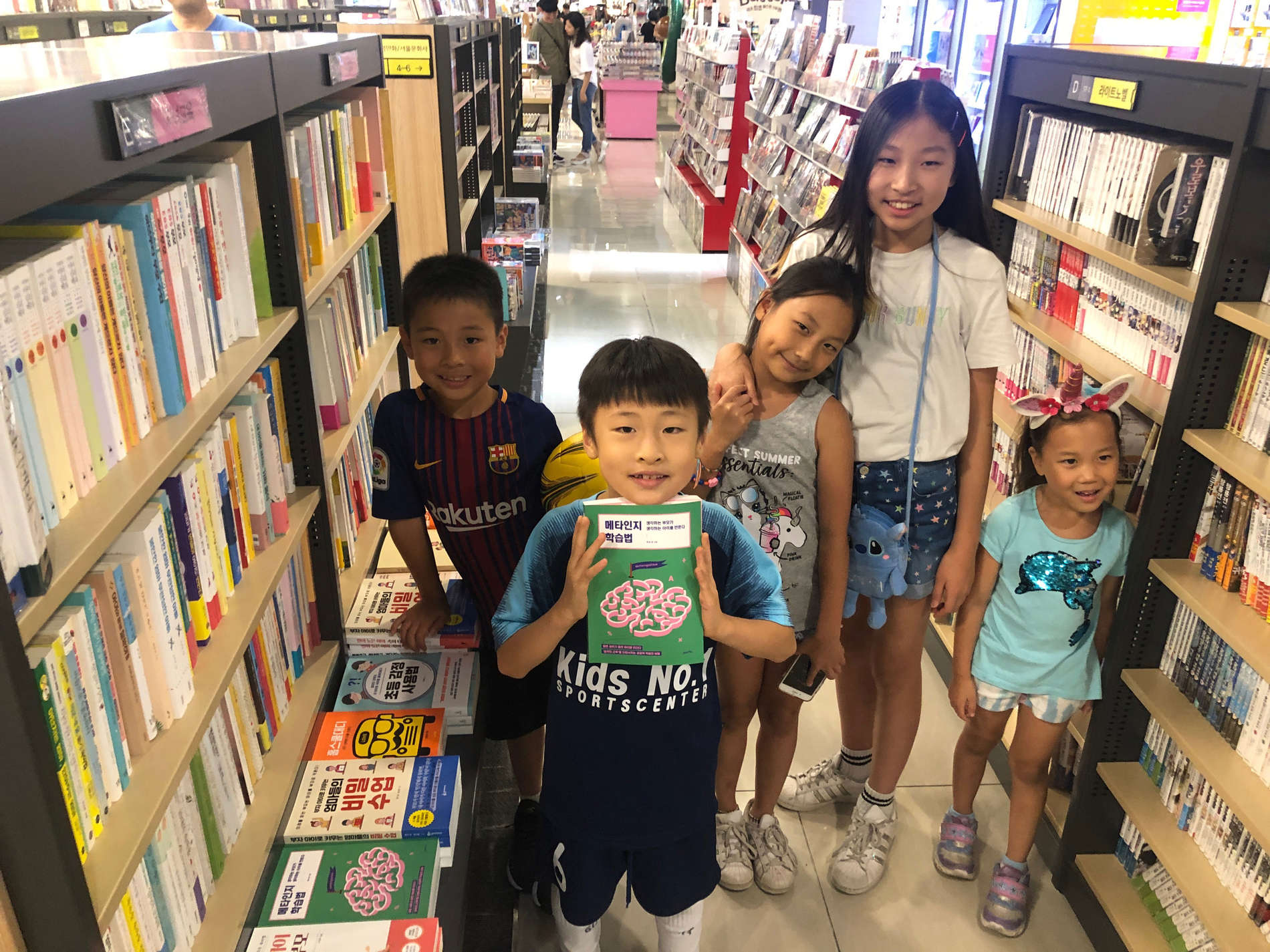

I wrote the book over Korea’s winter break, when my kids were also on break, and I often brought them with me to the cafes. My son had become interested in drawing mazes, which was the inspiration to the maze brain that ended up on the book’s cover. There were many instances while I was writing, and watching my kids, when I remembered the times I said the wrong thing or was impatient. I am so proud of my kids, and they are the biggest inspiration for the book. I cried a lot of tears while writing some sections. I guess metacognition does include reflections on your deepest emotions!

Did you pull from personal experience or history when writing?

The first time I heard the word “metacognition” was in my first year of graduate school at Columbia. I realized this was something we all think about since we’re young — this is the process of self-understanding in relation to others. For me, intertwined in the general definition of metacognition were added ideas stemming from my being Korean American. For instance, when I was little, I felt it was a bit more complicated to describe my identity. Could I truly assimilate into American culture? How Korean was I? Given the cultural differences, I felt that people’s self-reflections would differ by culture and experience.

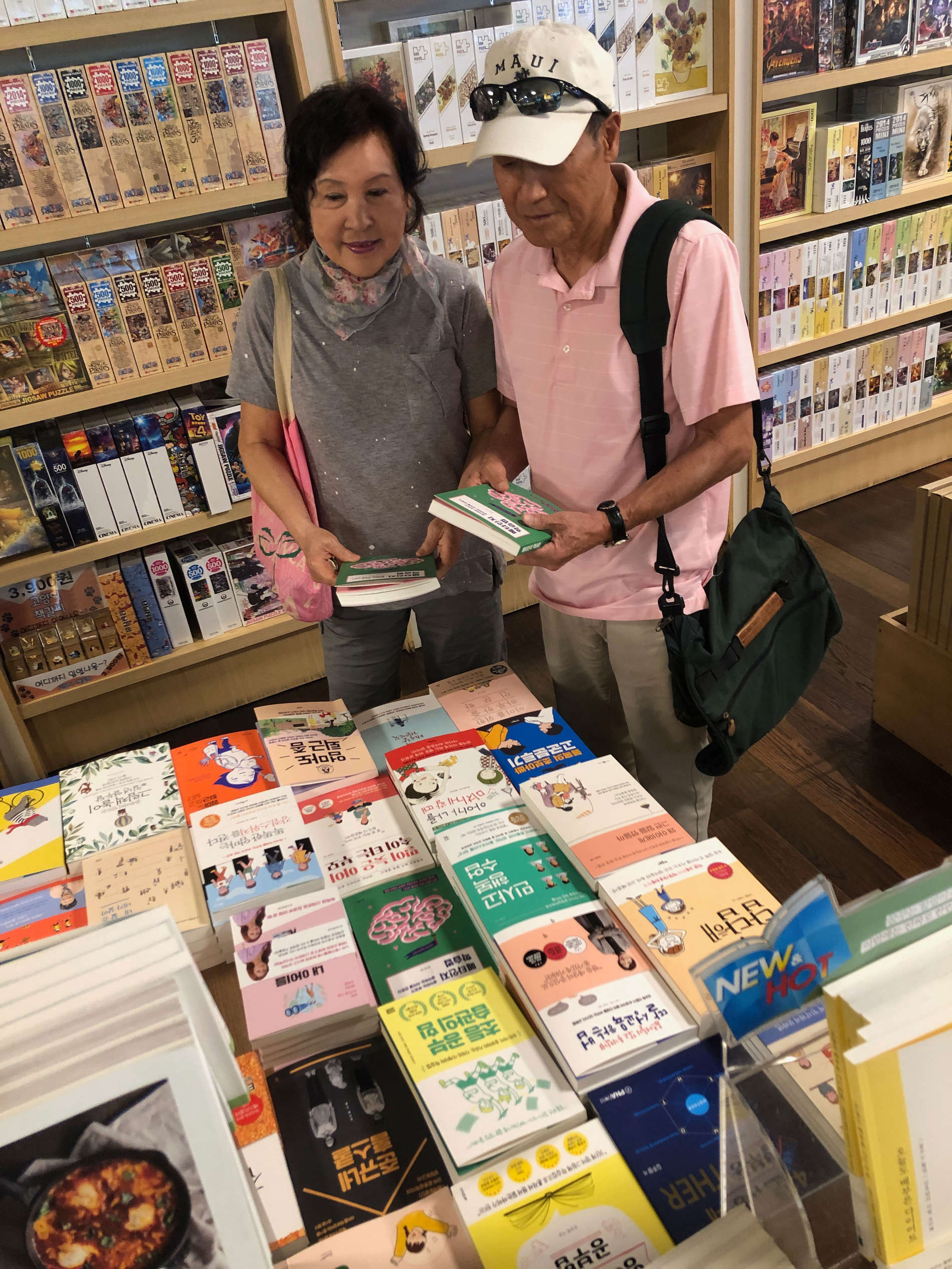

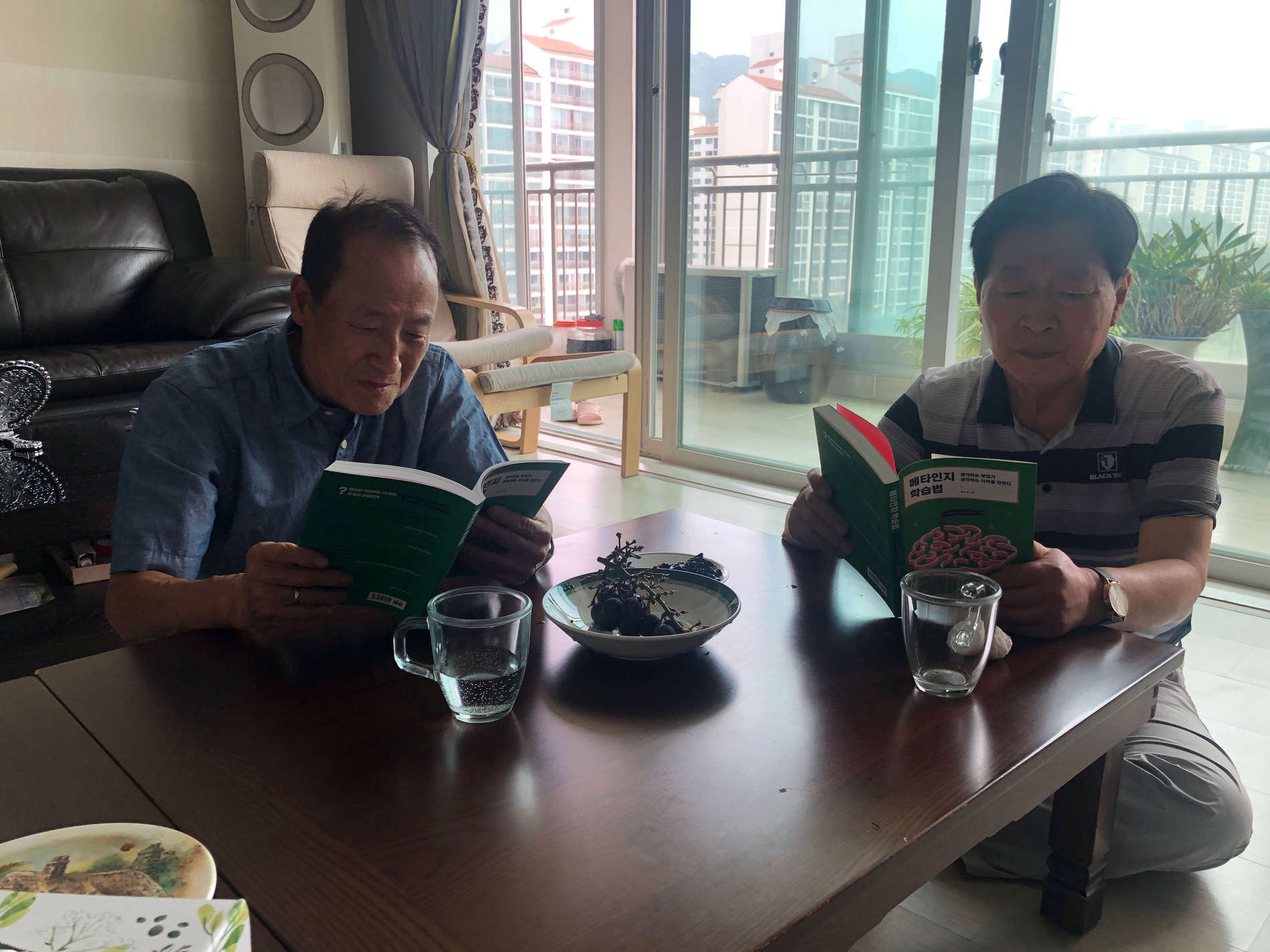

For my tenure party for Barnard, I printed my research tenure statement and presented it as a gift to my parents. But there was a part of me that thought, “The statement is in English; will my parents really understand the research that I’m doing? They immigrated here as adults, so how much will they get?” These thoughts made me happy and sad at the same time and incredibly proud of my parents’ journey and my identity as a Korean American. One of my most emotional moments writing this book was when, soon after it was published, my parents visited me in Korea for two weeks. You can bet that they both read the entire book immediately — a memory I will never be able to fully describe — and gave it rave reviews. I was so happy that my parents could read about my research and the things that are important to me, for the first time in their native language.

Why did you choose to focus on parents as a way to understand how children learn?

Parents spend so much of their time worrying about their kids’ academic careers. We hope our children do well in school, but we also hope our children learn to love learning. Given that educational systems across all cultures rely mostly on tests and grades, there is so much anxiety and stress, in children and in parents. I felt that much of the anxiety that children felt was learned from parents. In fact, I cite President [Sian Leah] Beilock’s work in the book that shows that parents who have high math anxiety could “transfer” it to their children. I hope that providing parents with tools to diminish some of the illusions that they have might also help to lessen anxiety.

Did you learn anything new about yourself while writing this book in a non-native language and foreign country?

I understood myself better because I had to think about why I had chosen to research metacognition and think of how to make the scientific data accessible to everyone, even in a culture that I had only observed but never lived. Fortunately, I discovered that all of the things that were important to me — relationships with family and friends, education, motivation, teaching, parenting — are works in progress in any culture, and understanding my own metacognitive processes was useful. Given that I was so aware of how much I didn’t know, I was probably more flexible and motivated to put myself in another’s shoes.

Did you encounter any other challenges, in addition to the Korean keyboard?

As for the title, the publishers first thought the word “metacognition” might scare readers away, so we had many discussions about it. For instance, it wouldn’t be strange to have a book called Metacognition in the U.S., but in Korea, titles are often an entire sentence. In the end, I convinced the publishers that we needed the word “metacognition,” given that in the long term I believed the [term] would become familiar to everyone. No surprise, when the book was published, I saw and heard feedback that people were interested but worried that the book would be too difficult. And I actually like this finding-the-courage-to-read aspect of my book, because difficult learning is what metacognition is all about.

Barnard experts explain.

Barnard experts explain.