It appears a historical moment has arrived, and the option to either become conscious, or to advance further down a road of self-reinforcing denial, presents itself as possibly a once-in-lifetime thing.

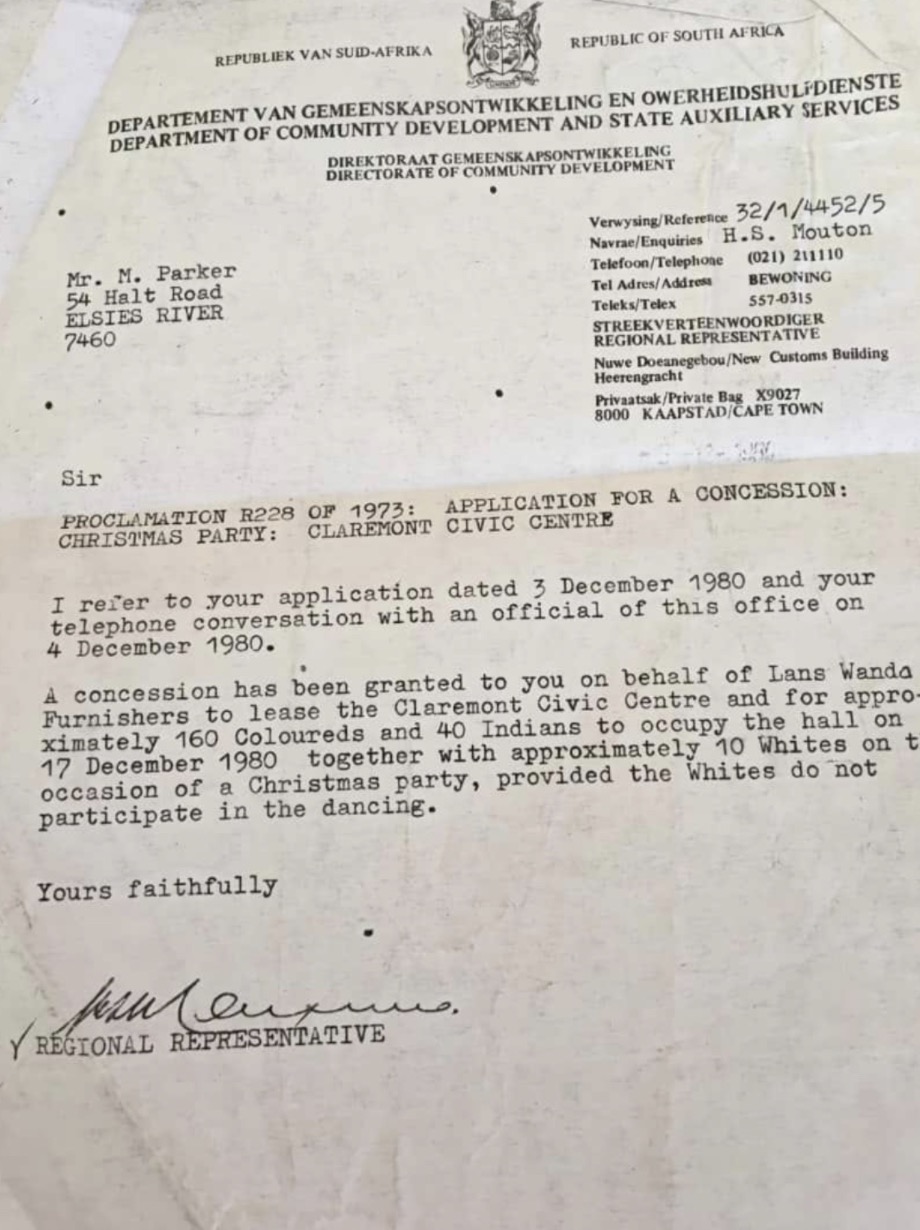

[Lede image: On June 16, 1976, high school students in Soweto, South Africa, protested for better education. Police fired teargas and live bullets into the marching crowd, killing innocent people and igniting The Soweto Uprising, the bloodiest episode of riots between police and protesters since the 1960's.]

Guy de Lancey is an award-winning artist and the Movement Lab’s designer, technologist, and manager. At Barnard, de Lancey draws on his background of more than 20 years in film and theater — as a director, cinematographer, lighting and scenic designer, technical design consultant — to oversee the lab’s collaborative use and project development. His interests lie in performance, human movement, and neuropsychology.

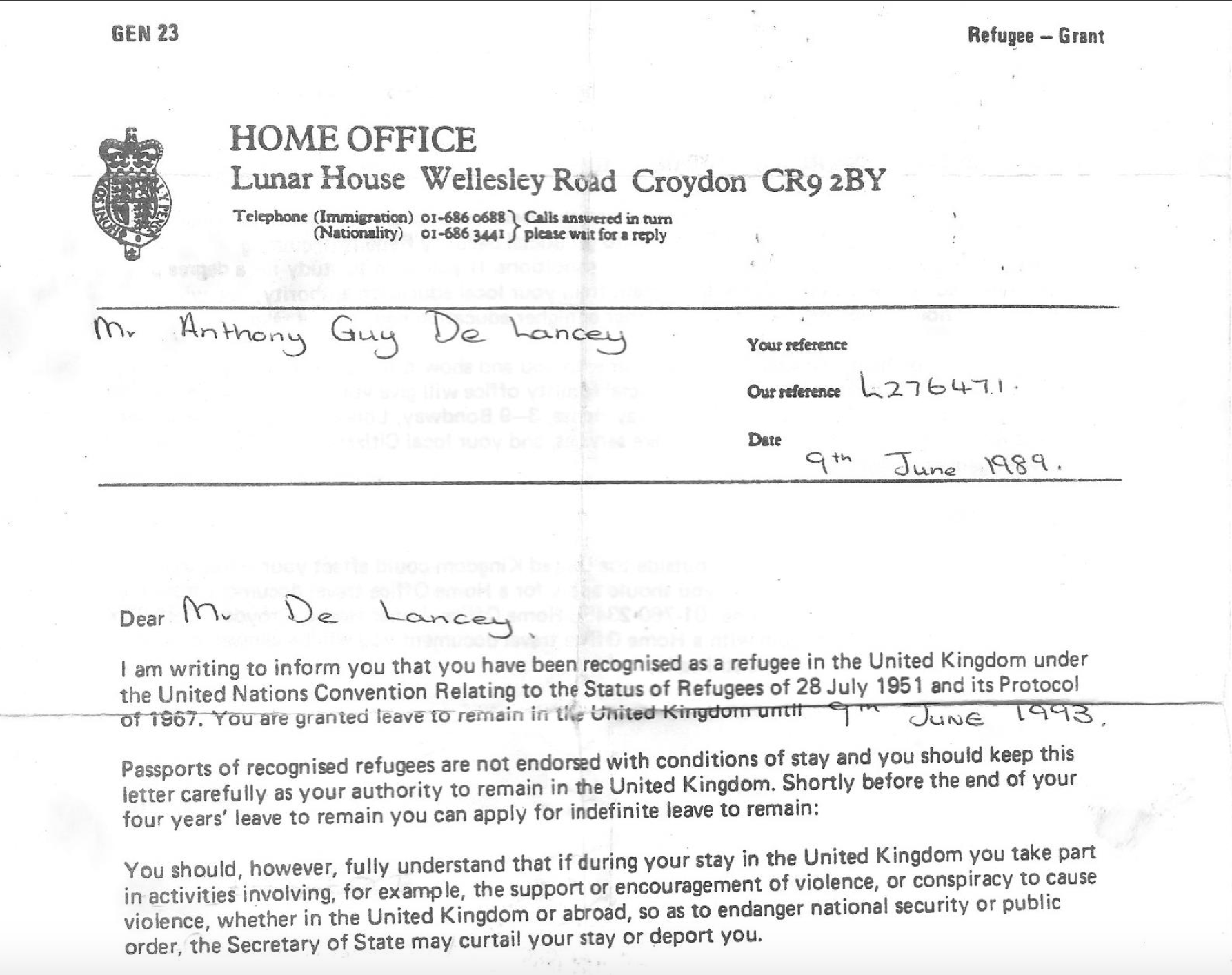

Given the current civil reckoning in the U.S., Gabri Christa, Movement Lab director and associate professor of professional practice in the Department of Dance, and the lab’s Post-Baccalaureate Fellow Allison Costa ’19 asked de Lancey to reflect on his experience of becoming a political refugee from South Africa in the Movement Lab’s first Artist Interview.

As de Lancey shares below, he left his home in South Africa in 1986, traveled to Europe, where he claimed political asylum for four years, returned to South Africa after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the release of Nelson Mandela, and finally settled in the United States in 2012.

To coincide with International Day of Peace (September 21), the College revisited de Lancey’s story and his journey from South Africa’s apartheid to the U.S.’s civil rights movement.

Below are excerpts from their talk:

What led you to leave your country as a refugee rather than accept the racist system there?

Growing up in South Africa — which had instituted a legalized system of racial discrimination and oppression and had attempted to present that system as a natural and inevitable order of social relations that should be depoliticized for both the oppressed and the beneficiaries of a suffocating colonial system of entitlement — it became clearer over time that my views about that system, out of necessity, had to be politicized in order to make sense of and deconstruct the mendacity of what was happening. And how I was raised as a child in a system of privilege.

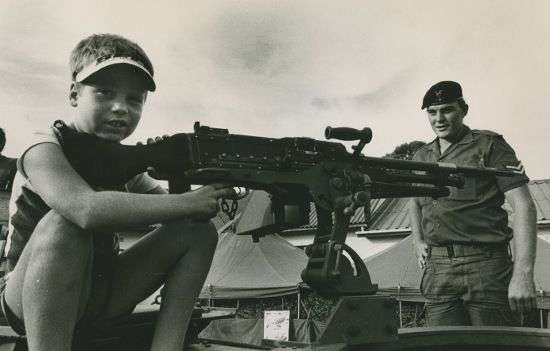

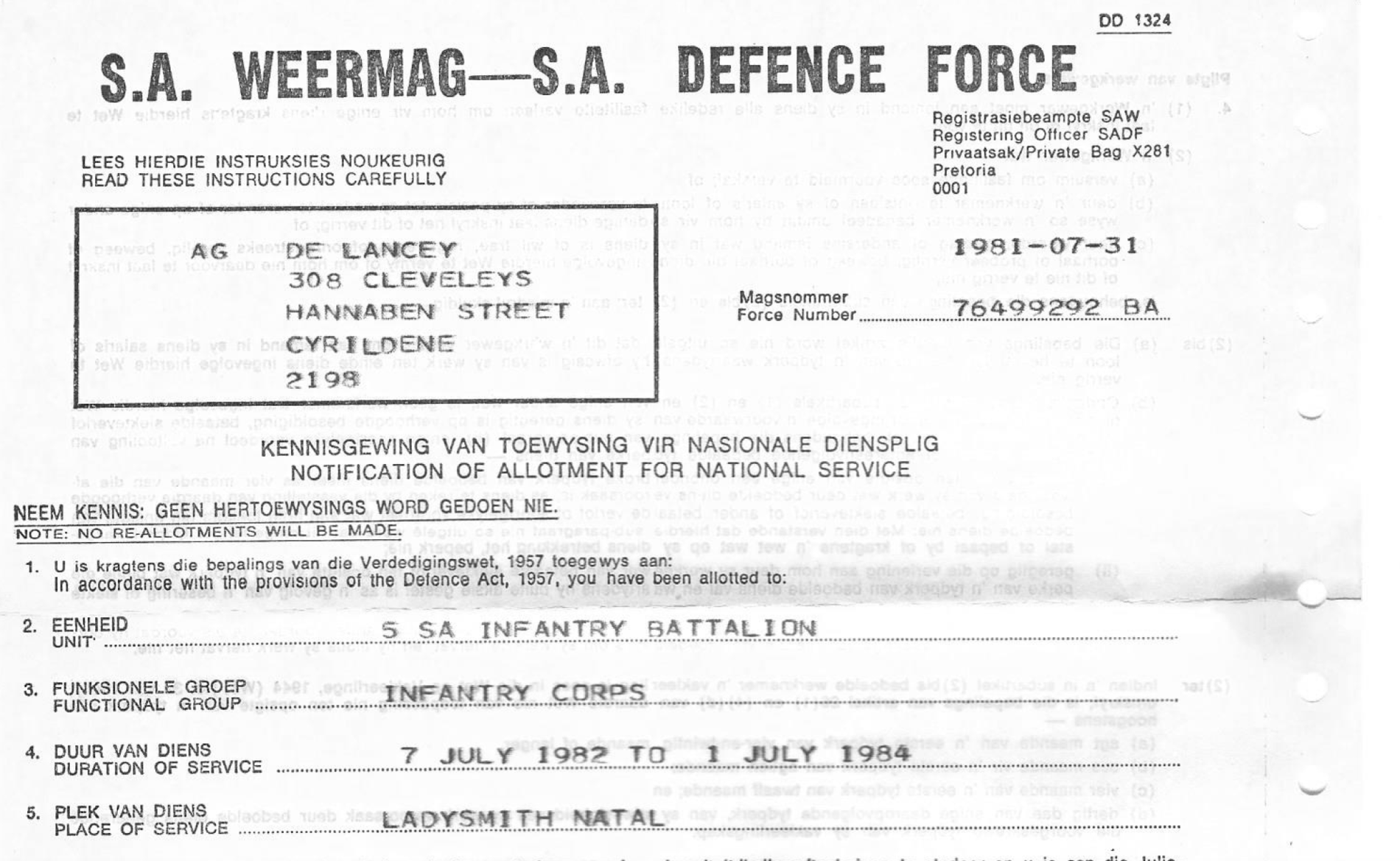

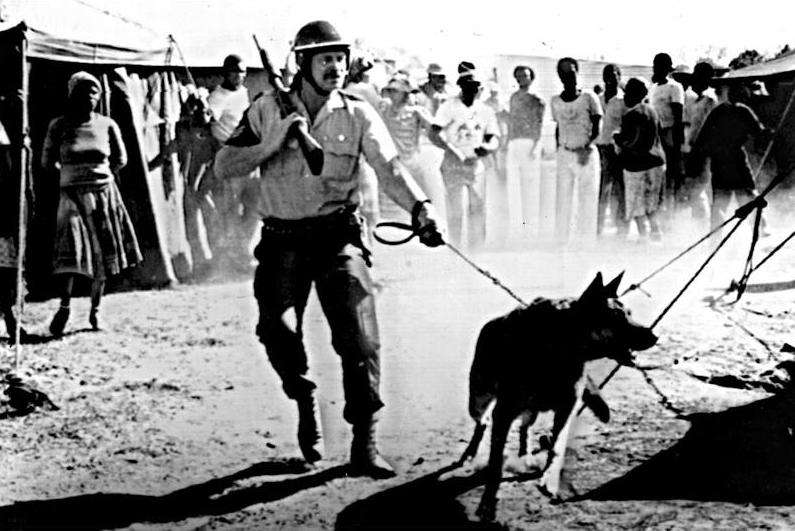

Part of the system of racial segregation was that young white men were faced with conscription into a military force that was designed along racial lines to oppress and disenfranchise fellow citizens. This was sold as “fighting terrorism” or “fighting communism,” not as propping up apartheid or dehumanizing the majority of the population and maintaining them in a position of indentured labor.

This arrangement was embedded in the Cold War strategies of the global powers and fully supported by the CIA, which after all was instrumental in alerting the apartheid government as to the whereabouts of Nelson Mandela, described [by them] as “the world’s most dangerous communist outside of the Soviet Union,” leading ultimately to his arrest. I felt I had to become aware of how official narratives functioned and to what end.

There was little choice in that system if one refused to go along with it or support it. For the treason of conscientious objection, I was faced with six years in jail. The option was to go “underground” and fight the system of government from an insurgent position, or go into exile. I chose the latter.

Can you talk a bit more about that period in your life? Your family relations and the decision that led you to leave?

I was a political refugee, motivated by political conscience and awareness of the brutality and sheer stupidity of the racial system of apartheid, as well as conscientious objection to supporting the military system designed to uphold that social arrangement. Now I am no longer a refugee but rather a privileged migrant.

Leaving one’s country and everything you know, becoming a refugee, is not an easy task. However, in my case, it is hard not to view it as a rather harsh severing of ties with homeland and family in relation to those whose lives were actually threatened and in severe danger. Racism is murderous.

Part of becoming conscientized to the political and cultural realities of your country and the circumstances of your upbringing often starts with observations of one’s immediate surroundings. The courage and will to ask questions about those realities and to test those observations against those close and immediate to you. It involved questioning, research, reading political literature, engaging in political discussion, developing the tools to penetrate and unmask official storylines, the rigged news media, accepted cultural cues and practices, the received and “normalized” racist views of one’s environment, school, family, colleagues, and society at large. It’s a process of stripping the veil of normalized deceit away — a concerted attempt to see clearer the source of tensions and abuses that were routinely covered up and hidden from a comfortable, privileged life.

The conflicts of political views and notions of justice with one’s family are at first the most hurtful and emotionally charged experiences. But that, obviously, is where one starts and hopes to begin to make a difference. At the very least, one hopes to encourage family and friends to become aware of what they cannot or will not perceive, of how what they do perceive has been ideologically served up to them in insidious and very subtle ways, of how what seems normal is anything but.

Being faced with prison, condemnation, or being threatened by frightened racists, however, is the least possible cost to be suffered when one has formed an ethical and political conscience against the inequity of social relations that are toxic to all who live with or under them. Becoming a refugee, while extremely hard psychologically, is relatively easy when one has become committed to shared views about the evils of a social system.

What is it like for you to learn about and function within another country’s racist systems after having grown up with racism in South Africa?

It feels like déjà vu. I was aware, from a distance, that the U.S. had a racist history. I was not aware how deep and virulent that history was until living here. I also learned, after living through a system of legally instituted racism, and seeing that system suffer defeat of some sort, that racism of that kind had always been a global project and that apartheid was alive and well all over the planet. That despite the pretenses of economic sanctions, disinvestment, and anti-apartheid sentiment in the “developed world,” it was the developed world that invented apartheid, exported it, and maintained it worldwide for centuries. It was always in the white man’s economic interest.

It seems, too, that the denial of the deep racist history in the U.S., which has led to this moment, offers the same opportunities to reconfigure accepted notions of entitlement, supremacy, rules of political engagement, received cultural practices of exclusion, and difference.

The power of money, the entrenched political and economic interests, and the fear of demographic fluidity, however, seem formidable here. The general depoliticization of life, too, seems insurmountable. Yet it appears a historical moment has arrived, and the option to either become conscious, or to advance further down a road of self-reinforcing denial, presents itself as possibly a once-in-lifetime thing. It would be an extremely destructive option not to take the creative and liberating possibilities of the first. Both for the disenfranchised and abused as well as the entitled.

As a white man actively rejecting racism in your own family and country, what lessons can you share with others, especially white people in this country, that could help people stand up for racial justice?

Begin with your immediate surroundings. Your family and friends. Politicize your thinking, your consumption of culture, your education system. When I say politicize, I do not mean preach from a pulpit, or use political correctness as a policing tool. I mean sharing the tools to articulate what is being actively hidden from you as a citizen through officially sanctioned discourse. I mean being aware of how systems of injustice function, how they are set up, and who they serve. How they are presented as the benign natural order of things. How they operate unimpeded in day-to-day engagement and how one can creatively, actively, subvert these.

Read literature that educates you on the political history of your country, its economic systems, cultural values, institutions, social relations, relations with the rest of the planet. Consider critically the sources of what you read. Share what you learn, with generosity and sensitivity to the fact that some might never have had the opportunity, nor the tools, to think of the things you may have discovered. Be honest. Think of honesty as a gift, not a threat. Do not shame or trade in guilt.

To read the complete, unedited interview, click here.

—Reprinted courtesy of Guy de Lancey, Gabri Christa, and Allison Costa ’19