In 2013, Celia Naylor — professor of Africana studies and history and chair of the Department of Africana Studies — was on vacation with her daughter in her native Jamaica. While there, they went on a tour of Rose Hall Great House in Montego Bay. Currently owned by a wealthy American family, the popular tourist site, which can be rented as a wedding venue, was a plantation on which hundreds of women, men, and children were enslaved from the 18th century to the early decades of the 19th century. The tour, however, did not focus on their lives or labor, but on Annie Palmer, a fictional “white witch” said to haunt the land. The myth of Palmer was taken from Herbert G. de Lisser’s 1929 novel The White Witch of Rosehall, which provides the tour’s talking points.

“I was so troubled by the tour that I could not stop thinking about it,” said Naylor. “I decided I wanted to write something about it. I thought, perhaps a poem, and then after some research I thought I might be able to pull together enough materials for a short article.”

Instead, as Naylor became more engrossed in the archival documents of Rose Hall, she wrote the book Unsilencing Slavery: Telling Truths About Rose Hall Plantation, Jamaica, which was published last July. It centers the lives of Rose Hall’s enslaved people, highlighting enslaved women and the violence they had to endure and navigate on the plantation. Naylor also critically analyzes the novel that gave rise to the white witch myth and the reasons why Rose Hall chose — and continues — to highlight it.

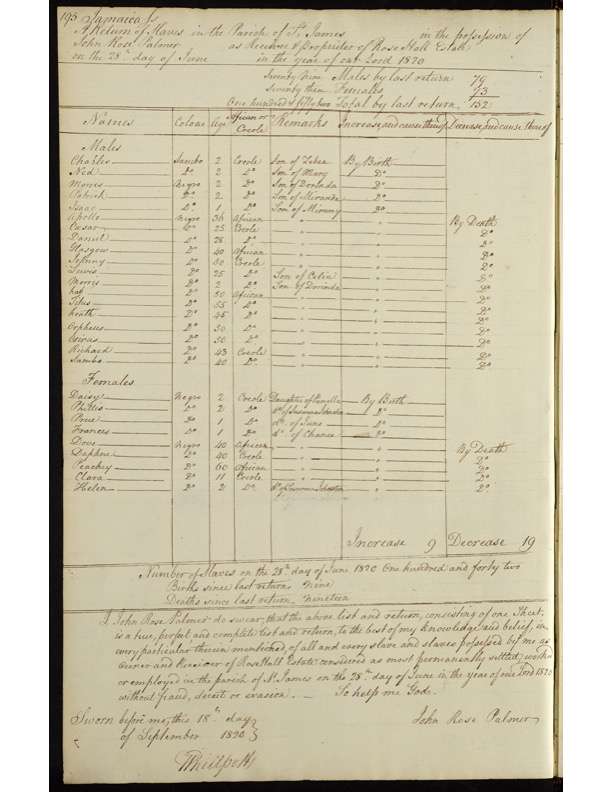

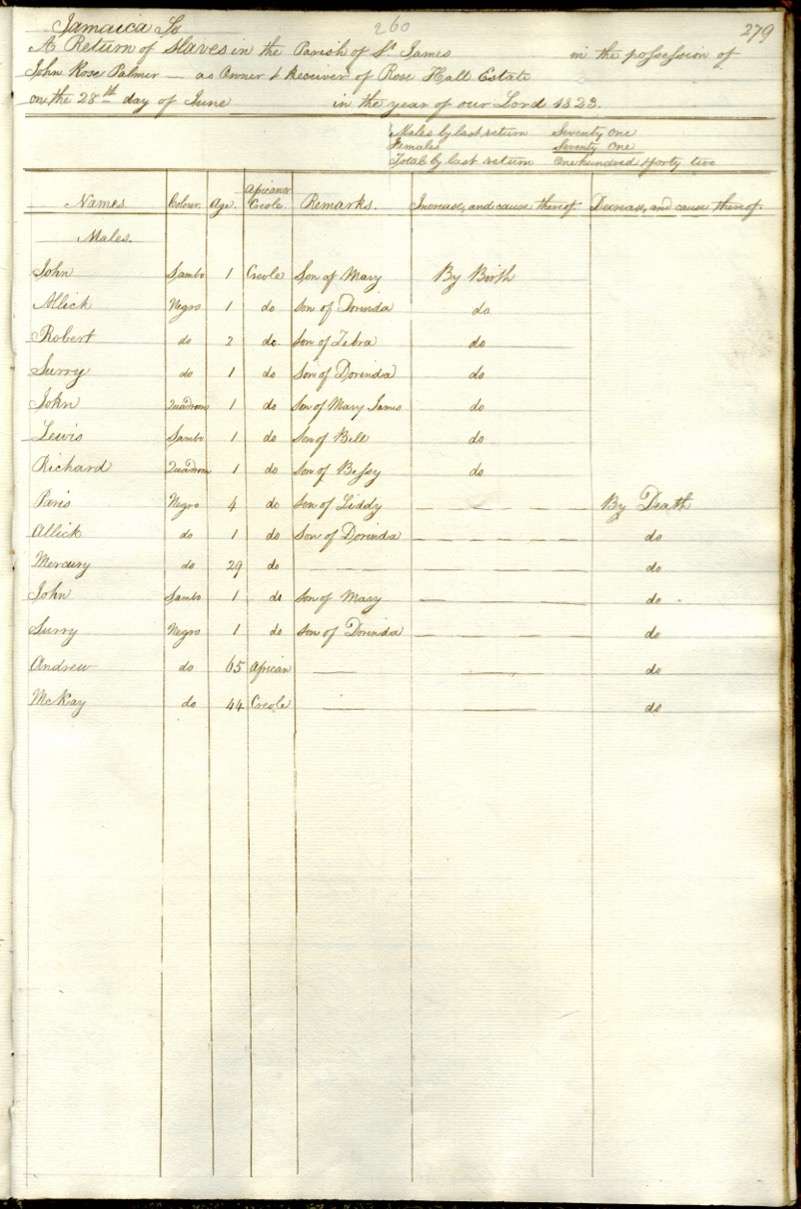

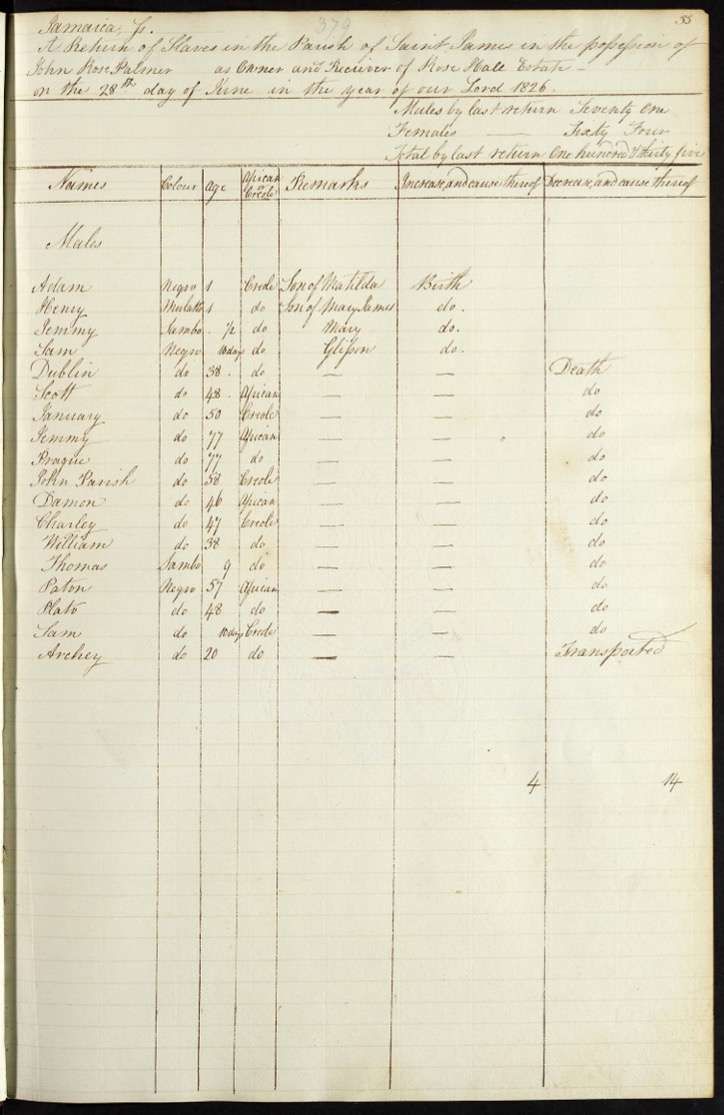

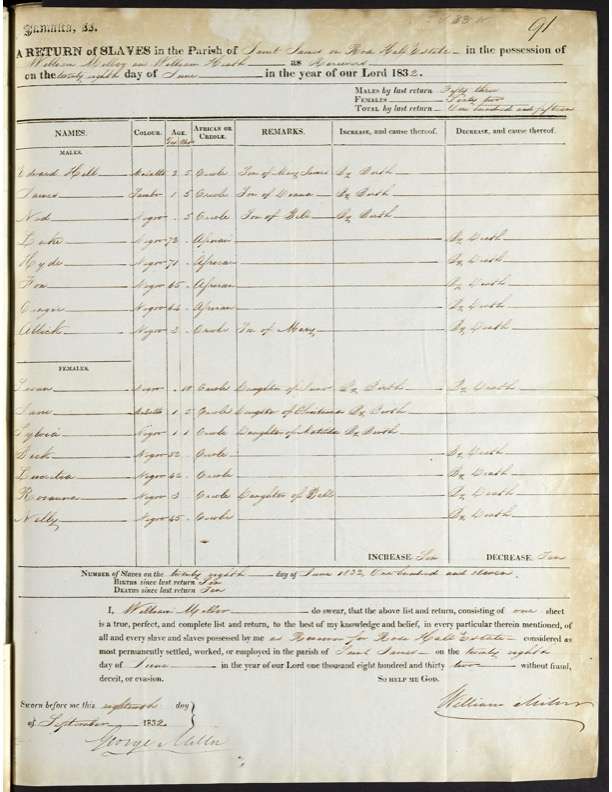

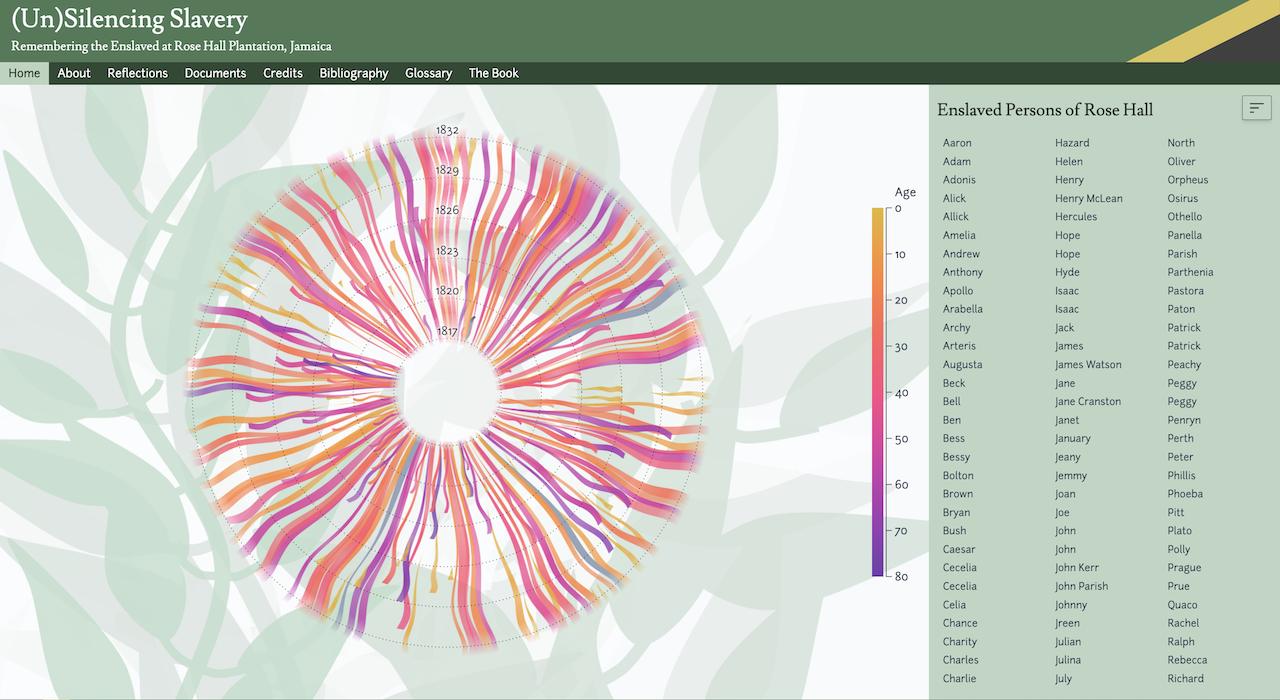

Naylor and her collaborators created an extensive companion website to the book as a way to memorialize and archive the lives of 208 enslaved people from the plantation. The website provides individual profiles, documents, and records to identify them. “My work centers on revealing the names and selected experiences of the enslaved persons who lived, labored, and, whenever possible, loved at Rose Hall Plantation,” she said.

Throughout the month of June, Naylor participated in three different conferences in the circum-Caribbean, including a presentation on her Rose Hall project at the biennial conference of the Association of Caribbean Women Writers and Scholars, which was held on the San José and Limón campuses of the University of Costa Rica.

In this Break This Down interview, Naylor shares how she used technology and historical records to tell the truth about Jamaica’s slavery past.

What was your research process for the project?

For the book, I focused on the final decades [1817-1832] of slavery in Jamaica. I was interested in unveiling the multifaceted aspects of enslaved people’s lived experiences at Rose Hall, particularly enslaved women’s experiences. I examined archival materials in the Jamaica Archives and Records Department in Spanish Town and the National Library of Jamaica in Kingston, as well as archival materials in England at the National Archives in Kew and the Special Collections at the University College London (UCL) library. I visited Rose Hall Great House several times and went through the tour during my many visits to Jamaica.

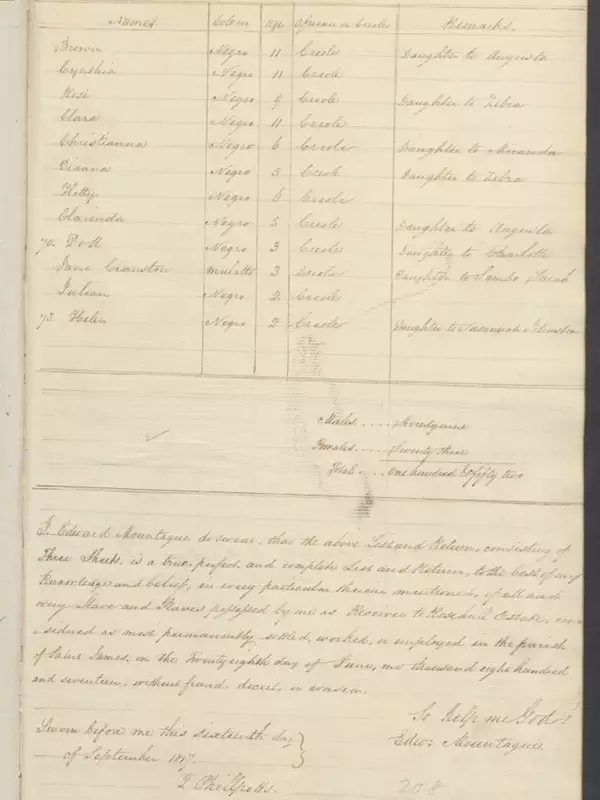

Major archival documents included the slave registers, which provide specific information about individual enslaved persons at Rose Hall from 1817 to 1832. In addition, the Rose Hall Journal, which is housed at the Jamaica Archives in Spanish Town, offered more information about the daily and weekly work activities of enslaved persons at Rose Hall, including information about child births by enslaved women, the names of enslaved people who had run away from the plantation, and the names of those who had passed, sometimes with information of the cause(s).

As I also integrated a critical reading of de Lisser’s novel, The White Witch of Rosehall, I read this book many times, as well as articles written about him and about different elements of the novel. I did not locate de Lisser’s personal papers, so I was not able to incorporate his reasons and processes related to crafting his novel.

How did you use “21st-century technology and human imagination” to tell the deeper story of the enslaved people of Rose Hall?

Telling truths about slavery at Rose Hall demanded not only unearthing enslaved people’s experiences out of limited archival records but also unveiling the afterlives of slavery embodied in a novel and tours at the Rose Hall Great House that instead centered the white witch. Even after I decided to include these aspects in this book, I recognized that the book would not be sufficient to demonstrate to a larger audience, in some small measure, the intricacies and nuances of the interlocking lives of enslaved people. It was crucial to move the enslaved people from the margin to the center of this history.

Early on [in the research process], I imagined a website that would offer another avenue to present these enslaved persons in order to counter the dominant master/mistress narrative in the “official” Rose Hall Great House website, and other internet sources that focused on Annie Palmer. I wanted to give visitors an opportunity to review selected historical documents about this plantation and worked with a dedicated team of exceptional collaborators on a companion website [that] centered the 208 enslaved persons who lived and labored at Rose Hall in the decades before the abolition of slavery in Jamaica in the 1830s.

It was crucial to move the enslaved people from the margin to the center of this history.

How did you address any research challenges that you encountered?

In order to offer some sense of the individual and collective lives of enslaved persons at Rose Hall, I presented possible interconnected elements of their lives. I also wanted to contextualize the limited shreds of information provided in the Rose Hall Journal with possible questions and scenarios that could deepen readers’ understanding of enslaved people beyond their names on the pages of a plantation journal.

Instead of a day in the life of an enslaved person, I reveal possible scenarios of enslaved people’s connections and the meanings they may have ascribed to particular events. By doing so, I create potential narratives about their lives in order to display on the page how to move from bits of information to possible lenses of understanding. Instead of discussing how we write history with limited archival fragments, I use the early chapters in the book as a pedagogical and scholarly demonstration of the actual writing of history based on these archival [materials].

What has it been like presenting this research, especially in the Caribbean?

I usually include a summary of the major aspects of the Rose Hall project in my presentations on the book, whether I am speaking to audiences in the Caribbean, the United States, Europe, or other regions of the world.

The major difference in my presentations in the Caribbean, especially in Jamaica, is that people in the audience in Jamaica are usually familiar with the legend of the white witch of Rose Hall. They are also the most surprised to hear that the information they have always believed to be factual about the white witch, and the information presented in the tours at the Rose Hall Great House, even today, is entirely fictional.