The return of Jhumpa Lahiri ’89 to Barnard this fall has brought her journey full circle — from being a student at the College to becoming one of the most revered voices in contemporary literature now helping to mold Barnard student writers.

“There are times when it feels so natural to be rushing into Barnard Hall in the morning and climbing the [same] steps, because I did that so many times as an 18-, 19-, or 20-year-old young woman,” said Lahiri, who rejoined the College community in 2022 as the Millicent C. McIntosh Professor of English and Director of Creative Writing. “I think that we must have muscle memory or something that just kind of allows us to start swimming in a body of water where we already learned how to swim.”

Lahiri holds an affiliated status in the Comparative Literature and Translation Studies Department and the Department of Italian. She is also a senior fellow at Columbia’s Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America. Her courses this semester, Exophonic Women and Art and Craft of the Diary, offer students a chance to explore writing beyond a native language.

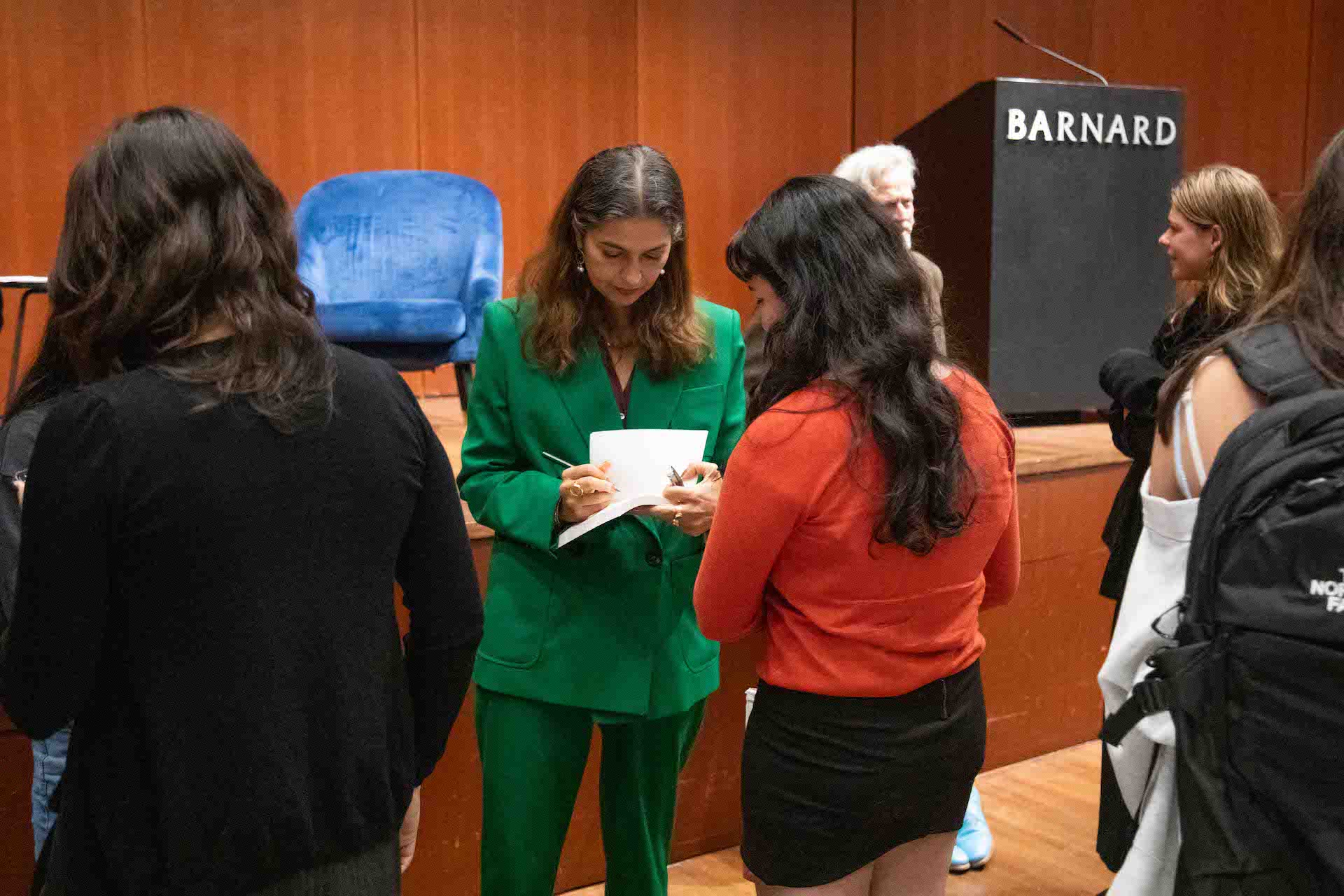

Lahiri’s return to campus was officially celebrated at the October 11 event, “Welcoming Jhumpa Lahiri: A Reading and Conversation with Brandon Taylor and Konstantina Zanou.” The talk was co-sponsored by Barnard’s English Department, and Columbia’s Italian Department and Italian Academy, and came one day after the release of Roman Stories. This is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s latest short story collection and her first that was written in Italian.

Before Lahiri sat in conversation with Taylor and Zanou, she shared how a deliberate immersion in transnational life has enriched her literary repertoire, deepened her connection to storytelling, and can offer a nurturing force for the next generation of writers.

Barnard is an origin point for you. How does it feel to be back?

The whole experience of coming back here has been very meaningful in that I’m sitting in the office of my pre-major advisor, Maire Jaanus — at her desk. It’s all very rich. And needless to say, at times also uncanny, filled with significance and resonance and surprise, and many “how did I get here?” kind of moments.

My first year back is very layered in terms of my deep past and my present reality intersecting. I’ve returned to Barnard with my children, both of whom are here at Barnard and Columbia. There are moments when I’m overwhelmed by it, and then there are other times [when being] here is just very comforting and familiar. I appreciate how much at home I still feel here. But it’s also strange to realize I’m now the professor [and] that I’ve written all these books. It still feels incomprehensible at times.

What’s on the horizon of your collaboration with Ken Chen and the English Department, as you hope to inspire more students to take up creative writing?

We’re still thinking about this. There is a lot of talk generally in the English Department about making offerings for first-year students more plentiful and more interesting. I think creative writing should be part of that, with a course for first-year students who don’t have to submit a writing sample — who can begin exploring just by signing up.

Your writing is at the crux of arrival, departure, and now, return. What was the impetus for returning to a short story collection, following Interpreter of Maladies (1999) and Unaccustomed Earth (2008)?

That’s what came. This is how this work emerged — in the form of a series of stories. I don’t really think very much about it beyond that point. I’m just grateful to have inspiration and something to work with.

When I was first writing the early stories, I was trying literally to learn how to write in Italian — how to put sentences together and create a story in a new language. And so, some of the stories grew out of that phase of intense [or] acute language learning and relearning how to write. Other stories came later, when I knew how to move the gears and make the thing move, allowing a story to unfold differently.

I think any act of writing in any language should be a liberation for the writer — the writer should feel free. I seek freedom in all of my writing. I seek the freedom to write, simply put.

How does writing exophonically liberate you?

The liberation is multifaceted, with the first element being that there’s a liberation from the former language — I’m not constrained by English. That’s not to say that Italian doesn’t constrain me in other ways, but it’s a kind of trade-off. English is the language of my formation, my education, and the expectations that were placed upon my being raised in this country. And in some sense, the learning of English came with an expectation of an act of assimilation.

I think writing exophonically — in my case, writing in Italian — is pushing back against that move toward assimilation, because even as I’m assimilating the English language, it is now more than ever the imperial language of the world and was certainly a colonial language for my family and parents. It’s very charged in that sense and resonates on both a personal and political level. So, that’s the first liberation [because] I think the first thing that the exophonic writer is looking for is a freedom from something. In my case, it’s a freedom from what English represented and what I felt that I was expected to do and who I was expected to be in English. I think any act of writing in any language should be a liberation for the writer — the writer should feel free. I seek freedom in all of my writing. I seek the freedom to write, simply put.

An exophonic writer [also] experiences a gravitational shift. That shift allows me to work in a new language because otherwise it feels very precarious. Writing in general is a precarious activity, and as we’re working with language, we never really know language, but we try to know it. [The exophonic writer] works riddled with [many kinds of] doubt — self-doubt, doubting the ability of language, doubting our own capabilities to control, utilize, or express oneself in language.

How do you shepherd your students to find their own linguistic shifts of gravity?

In the literature course, students and I are looking at a series of writers who had journeys in other languages or across languages. Each writer we look at had her own set of circumstances, her own story, her own struggles, her own relationships with the language(s) in question. So we are studying them week after week, reading and considering a series of questions together.

I [like to] share why I’m inspired to teach the class and why questions [about exophonic writers] are interesting to me. Students can think about linguistic shifts of gravity by looking at some basic questions: What makes a language? Can one belong to language? What happens when a writer moves into another language? Does this mean letting go of control or gaining new control? What does this mean in terms of authority, questions of authorship, and authority and belonging through language?

The course constantly circles around the question of belonging.

Is this course shaped by your own creative journey and transnational identity?

I suppose. I feel I’m the conduit — I’m at the helm. But we’re all on the journey, you know, and I’m sort of steering the ship.

Does your relationship to a writing project change from start to finish?

I’m accompanying the project. Essentially, I am the project, but I’m seeing where it goes and I’m trying to see it through. I don’t really step back to have a relationship with it. It’s too internal to have perspective on while it’s still in the making. [There are times] I think about it or step back and ask myself, “Okay, what am I doing here?” The impetus is simply to see it to the other side.

You’ve chosen to share, with your creative development, that metamorphosis is achievable. What’s at the core of this choice for you?

I’m moving through time as a person, as a writer, as a thinker, as a scholar, so as I move, I am aware at any given moment of who I am now and what I’ve been — sort of like how being at Barnard is an ongoing coming to terms with the fact of change and transformation and realizing that I am clearly no longer the young woman I was. But I am that person, I still am that person. I feel and I think that anyone who’s lived long enough will be stupefied by that.

The fact is, we do all change so much in the course of living. And so to think that the person, that young woman who was studying here [at Barnard], then became this person today — these transformations are things I marvel at. But in the act of living, we change, we grow, we transform, and writers are always looking at the passage of time and what it means.

If you could speak to your Barnard self, what would you tell her?

That it was all going to be okay.