Listening to Images is an exploration of racialized images in a genre of photography called “identification photography,” including passport photos and mugshots, and other images typically produced by or for the state to regulate citizens and their movement. Author Tina Campt—Claire Tow and Ann Whitney Olin Professor of Africana and Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies, Director of the Barnard Center for Research on Women, and Chair of the Africana Studies Department—not only looks at these images, but also listens to them. She examines several categories of photographs, including postwar photographs of black British men, late nineteenth-century ethnographic photos of rural South Africans, and mugshots of African American Freedom Riders in the U.S. South. Although these images are typically overlooked or dismissed as insignificant from an artistic point of view, Campt reclaims them and demonstrates that they are sites of creativity, refusal, and expression of a persistent hope for more. In this “Break This Down” interview, Campt shares her responses to several key images in her book.

Listening to Images is an exploration of racialized images in a genre of photography called “identification photography,” including passport photos and mugshots, and other images typically produced by or for the state to regulate citizens and their movement. Author Tina Campt—Claire Tow and Ann Whitney Olin Professor of Africana and Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies, Director of the Barnard Center for Research on Women, and Chair of the Africana Studies Department—not only looks at these images, but also listens to them. She examines several categories of photographs, including postwar photographs of black British men, late nineteenth-century ethnographic photos of rural South Africans, and mugshots of African American Freedom Riders in the U.S. South. Although these images are typically overlooked or dismissed as insignificant from an artistic point of view, Campt reclaims them and demonstrates that they are sites of creativity, refusal, and expression of a persistent hope for more. In this “Break This Down” interview, Campt shares her responses to several key images in her book.

Martina Bacigalupo, Gulu Real Art Studio, 2011–12. Courtesy of the artist and the Walther Collection.

Tell us about these discarded African identity photos. Why are these portraits faceless, and when we listen to these images, what do we hear?

These images were found in the garbage of a photography studio in Uganda. They were produced as “identity photos" that are used for identity cards because in Uganda it’s cheaper for the photographer to take a full-body shot and then cut out the face. A photojournalist named Martina Bacigalupo discovered this shop, saw the discarded images, and asked if she could have them; she and the photographer then began a collaboration that became an installation at the Walther Collection, located in Germany and New York.

What’s so compelling to me are the stories behind these images. I encourage people to listen to these images. We often think that images have an impact on us because of what we see, but my argument is that we need to open ourselves up to a broader encounter with the image that goes beyond what we see. What does it mean for this person to sit dressed in this way in that studio and need to have a photograph like this taken? What did these images mean for these people in their communities, and what do these images mean for us?

In these photos, I hear black refusal—the embodiment of practices of defiance, resilience, and dignity in situations where it seems black people may not have access to these things. How are they refusing to be relegated to a position of indignity? How are they refusing to accept the place they have been given in their society?

But these images have no face. How do we connect with people without a face?

My question is: Do we need a face to connect to someone else? We invest so much in eye contact and facial expression, but that can distract from the larger body of interactions. These images are a perfect example of an expression of dignity, of defiance, and of possibility.

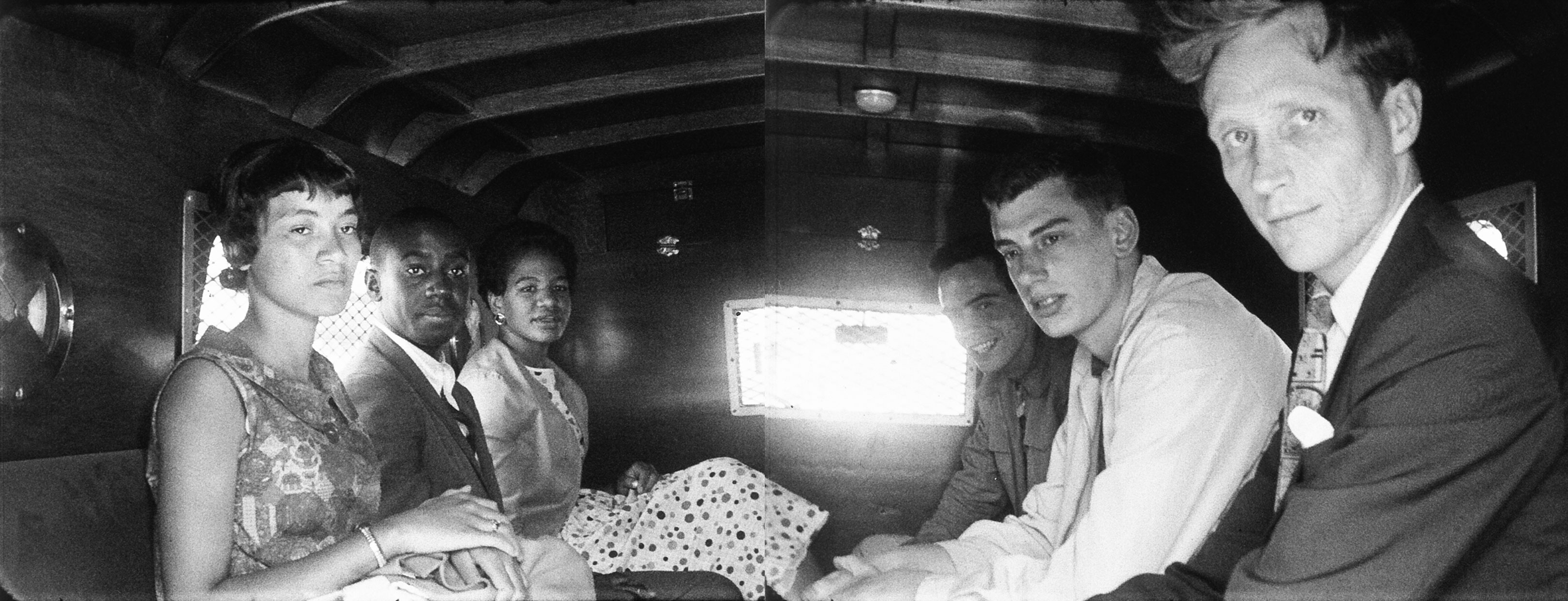

Photo composite by Eric Etheridge from "Breach of Peace"; archival news image courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Why are you drawn to this image of 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders? What’s the story here, and what is made audible?

One of the things I talk about in the book is the concept of "quiet photography." I distinguish between quiet and silence. Quiet is not the same thing as silence. Quiet is an audible sound that registers in the absence of the sounds that we recognize as aggressively present. It is like a hum—you hear it as a rumble. When I look at this image, the first thing that resonates for me is that these people are not speaking—but they are not silent, either. They are quiet. They are articulating something without speech or sound.

In this photograph, you see a group of people in a paddy wagon. This was one group of the hundreds of people who went to the Deep South during Freedom Summer, 1961, to protest and participate in sit-ins as part of the civil rights movement. This group is mixed; we see African American and white women and men. We see them in the cavernous back of a van with light coming through. Some are looking at us, and some are looking away, and except for the man in the back who is smiling, they appear stoic. They are all dressed up, having just been loaded into a police van after being arrested and on their way to jail.

When I engage these photos, I focus not just on these visual details. I try to ‘listen’ to the quiet practices of refusal they are participating in. I do that by lingering on the fact that the African American woman in the foreground is wearing a beautiful dress, and her hands are folded in this beautiful, elegant way. All of these African American protesters are dressed formally as if they’ve just come from church. But in fact, they’ve just come from a protest. We don't know if they were spat upon and shoved to the ground. We don't know what kind of violent encounter they just went through moments before this photograph was taken. But here they are—looking respectable and with all the dignity they have been denied. We don’t ‘see’ that in the photo. We must instead ‘listen’ to the larger story and attend to the quiet frequencies that surround and infuse these images with meaning.

From http://iftheygunnedmedown.tumblr.com/

You have said that the images that appear in #IfTheyGunnedMeDown: Which picture would they use? are a “photographic archive of dispossession.” What does that mean?

These photographs were originally part of a Tumblr called #IfTheyGunnedMeDown created in response to the way posthumous photographs of victims of police violence are circulated by news media. The posthumous news photographs are meant to give us visual evidence that these folks deserved to die because they looked dangerous and menacing. In response, a number of black folks across the country posted two images of themselves: one image showing the way they would want to be remembered and one image they thought would be used to demonize or disparage them and in doing so, dispute the complicated life they led. The interesting thing is that these individuals are projecting themselves into the future after they supposedly have died a cruel death. They felt the need to create their own archive of images to speak for them after their death. When I refer to these images as an "archive of dispossession," I am saying that black youth are put in the precarious position of being dispossessed of the possibility of their own future, before they even have a chance to create a future for themselves.

Listening to these images, their message to us is: "It doesn't matter what I do; my life is going to be defaced just by virtue of the fact that I am a black man. There is a high chance I will die in an encounter with a police officer. If that happens, you will circulate a photo of me to show I deserved it, so let me do the work for you. I am going to confront you the impossibility of the situation I’ve been put in. I am both the 'thug' you want to see in me, as well as a dignified, respectable person."

Both images are real, and these folks are embracing the complexity that is denied them. I am interested in this counter-move—when people who are left with no choice but to embrace that lack of choice and turn it on its head.

How is your project feminist?

Feminism has been misunderstood to be about "women's rights" and the "status of women." But black women have always been in a position of having to address their racialization as well as their discrimination as women. They are caught between fighting for rights for women and empowering black communities. It's an impossible choice because black women have to always think about both of those things at once.

Black feminists have taught us to think about race and gender as inseparable. I'm deeply accountable as a feminist to understanding the complicated ways black masculinity and black manhood are being attacked because of the ways in which blackness is gendered — just as gender is racialized.

My project is feminist because it's inspired by feminist theorists who ask us to engage the complexity of black life as a gendered phenomenon. It is about simultaneity—seeing the ways in which individuals are ensnared in a complicated nexus of race and gender.