On August 18, 2021, a new 8-foot tall, 800-pound sculpture arrived at its temporary home between the Diana Center and Altschul Hall. Weecha, brought to campus via a collaboration with Professor Joan Snitzer, director of the visual arts program in the Department of Art History, is on loan to the College from August 2021 to July 2022 to coincide with the celebration of the Barnard Year of Science.

Who, and what, is “Weecha”?

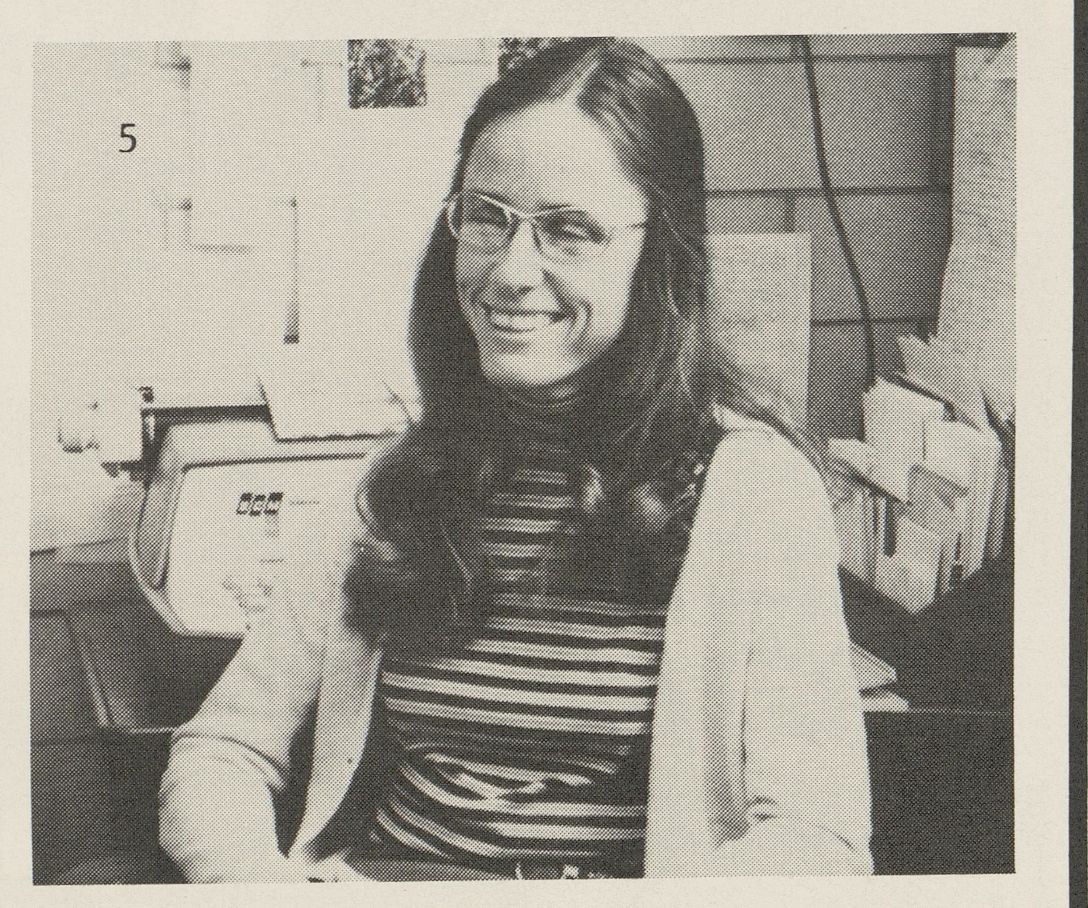

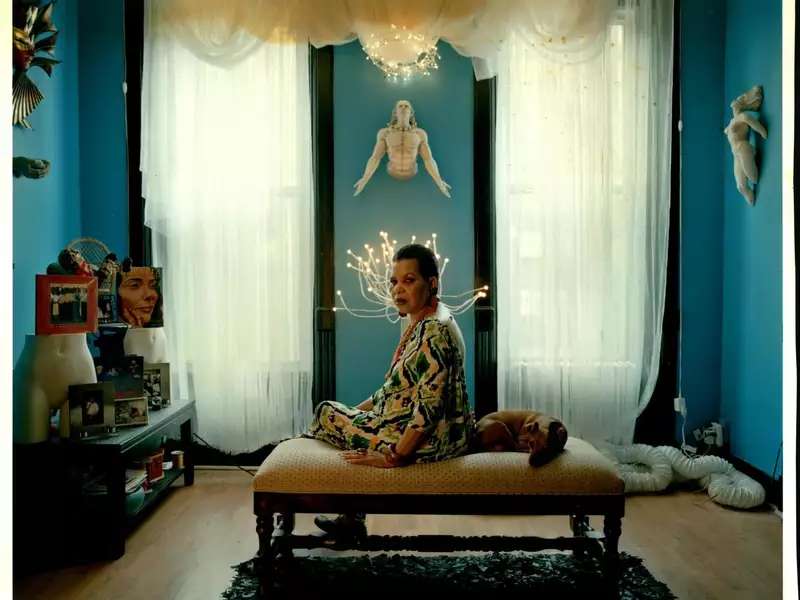

Created by Henry Richardson, a glass sculpture artist based in the Berkshires, Weecha was inspired by his thesis advisor and professor at Bryn Mawr, Maria Luisa “Weecha” Crawford. Now age 82, Crawford has left an amazing legacy in the fields of geology and petrology. After graduating from Bryn Mawr in 1960, she studied at the University of Oslo in Norway on a Fulbright scholarship (1960-61) and received a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1965. That same year, she joined the faculty at Bryn Mawr as an assistant professor. Throughout her tenure at the college — she retired in 2006 after 41 years on the faculty — Crawford served as department chair and helped spearhead the creation of the environmental studies program at Bryn Mawr.

Despite the fact that Crawford was in the minority as a female scientist, she made major strides in her research as a metamorphic petrologist, earning her high acclaim and recognition. In 1993, she was honored with a MacArthur Fellowship for advancing the understanding of the Earth’s resources through her study of metamorphic petrology and geologic terranes. “Weecha entered the sciences in a completely male-dominated field in the early ’60s and was highly respected and very successful,” said Richardson.

Geologically Inspired

Richardson first crossed paths with Crawford, fondly referred to by students as “Weecha,” in a Geology 101 course at Bryn Mawr; the college has a symbiotic relationship with Haverford, Richardson’s alma mater, similar to that of Barnard and Columbia.

The class piqued Richardson’s interest. As a student in Crawford’s classroom, Richardson admired her unique way of looking at the world and how she challenged traditional thinking patterns. “One of the most difficult things to do is to think beyond the typical or normative thinking,” said Richardson. “Weecha was adamant about exploring ways to look at information or ideas that didn’t conform to the way that most people were thinking about it. And so, if nothing else, really fostering a sense of exploration, and interest, and perseverance was really important.”

At the end of his sophomore year, Richardson decided to switch his major from economics to geology. “I really liked geology; it encompassed all of the sciences: chemistry, physics, and biology,” he said. He also pursued his burgeoning interest in art, taking several classes outside of his major. His background in the arts and sciences is one of the reasons he’s been so successful in his work as a glass sculpture artist, a profession that requires knowledge of both disciplines.

Crawford encouraged Richardson to explore the geological terrane of Kennett Square in southeastern Pennsylvania for his senior thesis project. He spent six months driving around the region and collecting samples. A few years ago, as Richardson was rummaging through his hammer drawer, the sight of his geology rock hammer from his college days brought Crawford back to his mind. “That just took me all the way back to being in the field with her,” he said. From there, he began the energy- and time-intensive work of creating the layered sculpture of bonded, chiseled glass in the interpretive form of a figure that would become Weecha. “She was in the back of my mind as I was making this form,” he said.

"I am particularly struck by both the form and the reflective light created by the glass and pigmented materials. I can't help but notice its resemblance to the Barnard blue and its seemingly figurative and organic form," commented Professor Joan Snitzer. "I hope the viewers' experience is a reflection on light, rising upward, symbolizing hope and their own spiritual and intellectual futures."

To craft his sculptures, Richardson chisels large sheets of plate glass using a hammer and binds the smaller fragments together using a silicate polymer activated by UV light. The result is a stunning array of translucent sculptures in the shapes of orbs, spheroids, towers, and, in the case of Weecha, a spiral figure that resembles the structure of DNA. An important element of Richardson’s sculptures is light, which is tied to his Quaker belief that God is light and that there is an inner light in every human being.

Women in STEM

As Barnard kicks off the Year of Science, the focus is on equipping women in STEM with the skills and resources they need to succeed in their respective fields. This is especially topical as women continue to be a minority presence in STEM, constituting only 27% of STEM workers, when they made up nearly half of the nation’s workforce in 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The gap is far wider for Black women, who hold only 2% of STEM jobs nationwide.

Women’s colleges, like Barnard and Bryn Mawr, have a critical role to play when it comes to increasing female participation in the sciences, Richardson believes, and Crawford is a shining example of that. “Barnard is an institution that is very eager and excited to have its students go into science,” said Richardson. “The history of women going into science from these women's colleges is really important.”

Visitors to campus who view Weecha can learn more about the artist and the sculpture by using their smartphones to scan the sculpture’s QR code.