Erika Kitzmiller is deeply passionate about understanding educational inequities. Earlier this year, the term assistant professor of education penned an op-ed that questioned legislators’ willingness to adequately fund Philadelphia schools and drew a connection between educational inequality and infrastructure in the Washington Post last August. At Barnard, Kitzmiller helps her students to interrogate the purposes and aims of education policy and education in an unequal society.

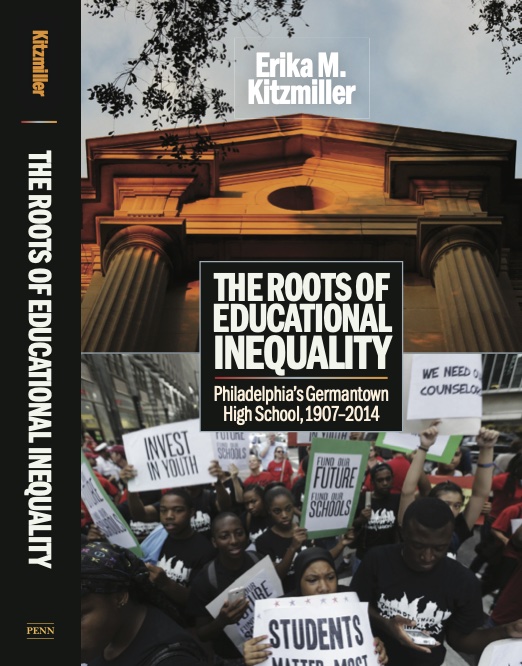

The work is as personal as it is professional, considering that she was a first-generation college graduate who then used her scholarship to produce inquiry-driven, practice-based methods to advance equity and justice, which she does on Barnard’s campus, as a research affiliate with Columbia University’s Institute for Urban and Minority Education at Teachers College, and via her newly launched online book club. In December 2021, Kitzmiller published The Roots of Educational Inequality: Philadelphia and Germantown High School, 1907-2014, which chronicles a high school’s century-long transformation from being considered a successful example of quality education to a school that was ultimately shuttered due to low academic achievement.

To better understand the role that funding and policy play in urban public schools, in recognition of International Day of Education (January 24), Kitzmiller discusses the research behind her book in this “Break This Down” interview.

Why did you use Philadelphia’s now-closed Germantown High School as a case study in The Roots of Educational Inequality?

On February 24, 2007, newspaper headlines spread throughout Philadelphia documenting a serious assault on a teacher who worked at Germantown High School. At the time, I was conducting research on university-community relationships at the Henry C. Lea School, located a few blocks from the University of Pennsylvania’s campus, where I was a graduate student in the School of Education and the history department. A few days after the incident, Lea’s principal, Michael Silverman, told me that he had been hired as the next principal of Germantown High School and would not be returning to the Lea School the following year. I asked if I could follow him to Germantown to study his leadership. Silverman had a long track record of turning around challenging schools in the city, and I wanted to document his work and share it with others. I spent the year at Germantown, watching his work and engaging with teachers and students.

When I spoke to the teachers who had been in the school when this violent incident occurred, many said that these incidents — reckless assaults on staff and students — were commonplace and tied to the poverty and hopelessness that many of their students had experienced for decades in the city and that the school had once been a first-rate institution, an anchor in the community that drew middle-class families to the neighborhood for its schools. As they spoke, I had doubts that the school’s past history was as perfect as they often described.

And as a public and private school teacher, I knew that schools were imperfect places. Rather than study Germantown High School’s magical turnaround, I decided to study the school’s history in the hopes that it might shed light on the roots of its 21st-century challenges.

What has the book’s research taught you about the ways in which education, race, and social inequities have intersected over the past 100 years and the resulting outcomes?

There were many things that surprised me, but the biggest surprise is actually the central argument of the book: that the factors that generated educational inequities based on class, gender, and race were embedded in the foundation of our public schools. These inequities were not simple byproducts of postwar white flight, failed desegregation, or school privatization but rather were woven into the fabric of schools since their founding, in this case, at the turn of the 20th century. Many school officials and white residents exacerbated these inequities through the policies and practices that they demanded, implemented, and sustained in the city, the school district, and their public schools for more than a century. At the same time, Black advocates and their allies resisted the policies and practices that limited educational access and opportunity and, in doing so, helped to create more just and equitable outcomes for poor youth of color who now make up the majority of Philadelphia school-aged youth.

What does your research suggest about how funding and philanthropy affect the nation’s urban public schools’ political economy?

First, let me define political economy, which refers to the ways that public policy and government regulation shape the economic, political, and social welfare of American youth. As my book shows, educational funding has never been provided at the level that schools actually need to operate effectively. Educators, families, and youth have always struggled to provide basic resources, adequate teacher staff, school facilities, and classroom materials. The story of this one high school shows how at the turn of the century, Germantown High School families and community members banded together to provide children with the additional funds and resources to subsidize inadequate public school funds and to create and sustain extracurricular programs and institutions, such as the Boys Clubs, the Germantown Settlement, and the YMCAs, that provided after-school activities and programs, particularly for low-income youth who called the community home. The additional resources and institutions in the school and community provided essential support to Germantown youth that one simply could not do on government funding alone. Over time, the philanthropy that supported these programs, activities, and institutions evaporated, forcing educators inside Germantown High School to fund the school on insufficient government aid.

What exactly are “doubly advantaged schools,” as defined in the book, and what does the educational system — and students — lose as a result of their existence?

I define doubly advantaged schools as institutions that served more white and affluent students and thus could leverage and rely on private philanthropy to subsidize inadequate public aid. They are doubly advantaged because the children who attend these schools have social and economic advantages due to the social and financial capital that their families possess, and the school, in turn, builds on these advantages by pressuring families to donate generously to their children’s public schools.

The over-reliance on philanthropy generates massive inequities, even within one school district. Oftentimes, doubly advantaged schools are only a few city blocks away from schools that have to rely solely on inadequate public support. When we don’t acknowledge these advantages and their corollary disadvantages, we can’t see the inequities that exist in our own communities and schools. Instead, we as a society often blame educators, families, and youth for the inequities that together we collectively generate.

Moreover, [this kind of] philanthropy masks the challenges that all schools face in underfunded school districts in rural and urban communities. This weakens our collective fight — across class, race, and space — to secure more government funding for under-resourced schools and communities.

History is not inevitable but rather is shaped by human action and inaction.

What are some of the biggest policy missteps you found in your research, and how can cities and the country course-correct?

When I was writing my dissertation, my history advisor, Michael B. Katz, always pushed me to recognize the alternatives that individuals might have chosen. As I revised the dissertation for the book, I often thought about this advice. For example, one could have imagined a system in which schools were equitably funded, where private funding was distributed to all the schools in Philadelphia, rather than to those that were already advantaged. Or where individuals took the steps necessary to desegregate the city’s public schools and where the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania funded schools based on a fair and equitable funding formula. All of those options were possible, but as I say in the book, elected officials, local educators, and white families often lacked the political will to create a system of schools where all children could thrive. History is not inevitable but rather is shaped by human action and inaction. That is what I hope my work conveys.

What was the biggest takeaway you learned from your research?

In my December 2021 book talk at Barnard, one of my students asked [that exact question], in addition to “What was the thing you wanted people to learn?” At the time, I said that I wanted people to think of how their actions affect not only their children’s lives but the lives of children in their city, community, or town. I want people, particularly those with advantages and privileges, [to know] that their actions and decisions have ramifications for other people’s children. I hope that my book allows readers to understand the history of one high school in the context of its city and nation and then to reflect on their own schooling experiences and choices in their lives and homes.