The 2020s began with a pandemic that helped confirm the important roles that science and technology play in everyday life, demonstrating that both can be used in inventive ways. A prime example has been the use of devices to stay connected to friends and family, from holding virtual dinner parties to hosting dance parties on Zoom. Earlier this spring, assistant professor of computer science Mark Santolucito encouraged the 23 students in his Creative Embedded Systems course to conceive of and implement their own creative uses of computation by producing kinetic sculptures — sculptures that move.

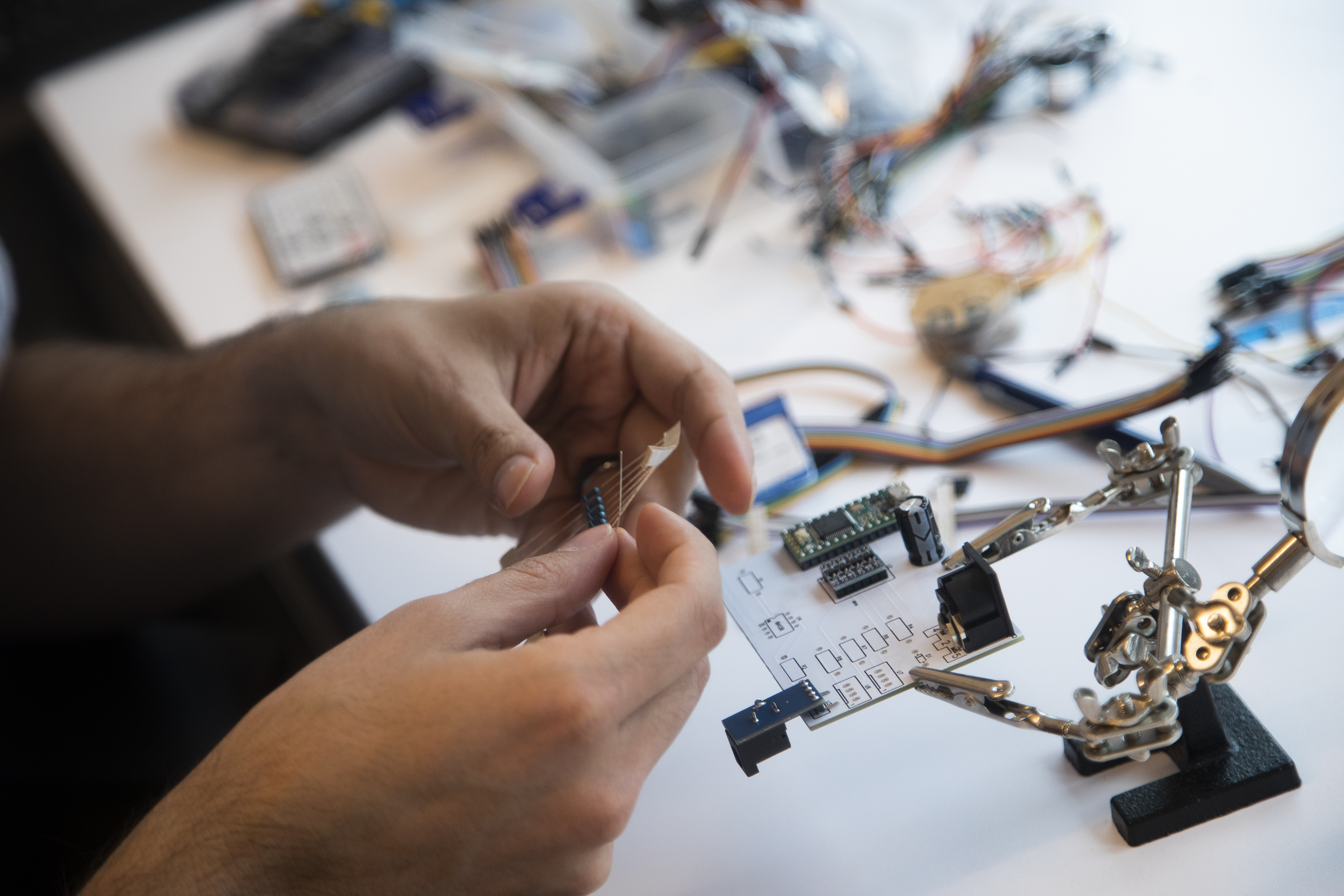

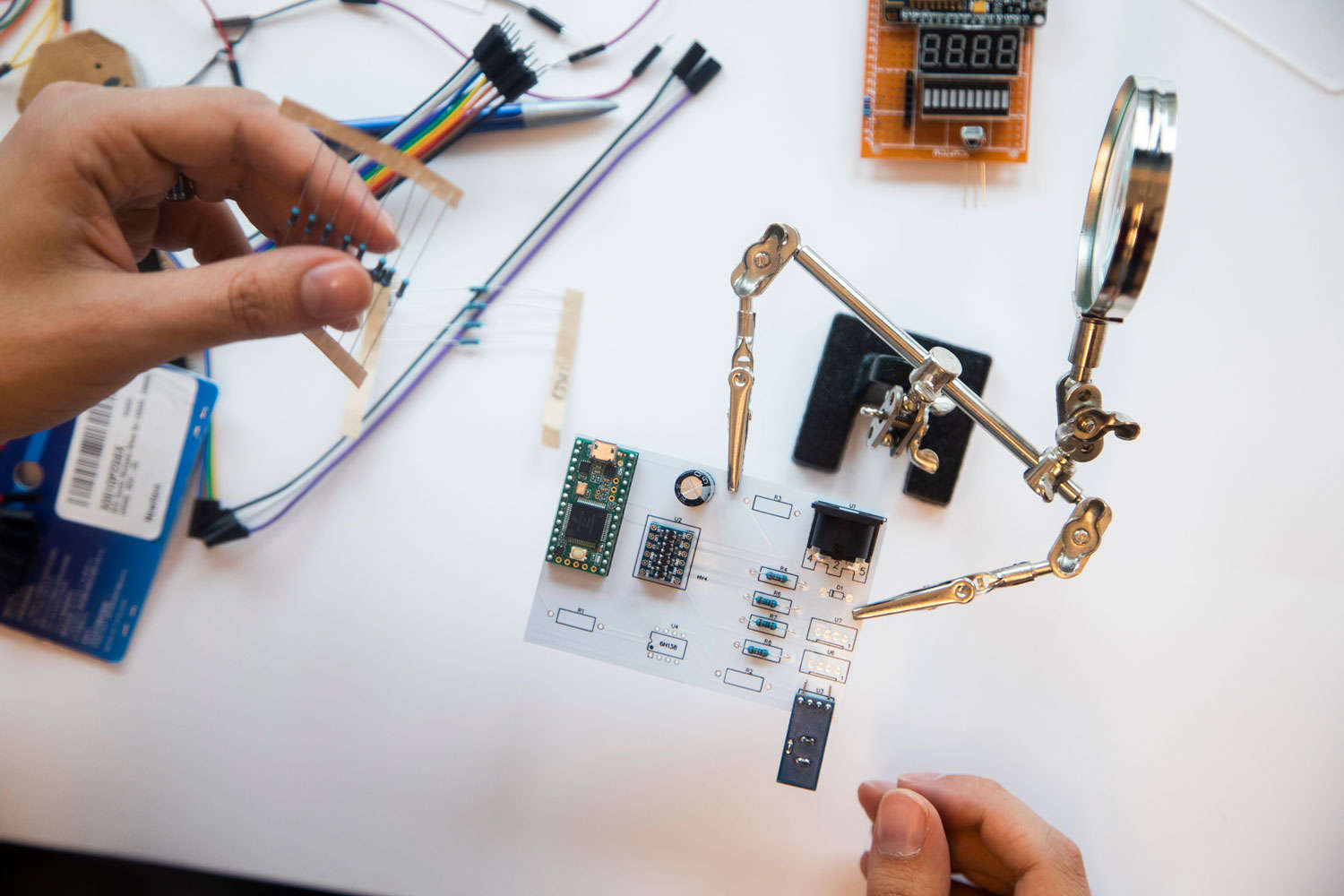

To teach the class remotely, Santolucito employed every movable device and technique at his disposal during labs and lectures, such as an overhead desk camera to show students the pieces he was discussing. Students who lived near campus had access to the College’s Design Center in the Milstein Center for Teaching and Learning, where they could use its tools and technology, such as drills and 3D printers, to make their projects a reality.“Students were required to build and design from scratch a creative sculpture that connected to motors and the internet, so we can trigger all of these sculptures remotely at the same time,” said Santolucito. “I provided some high-level configuration constraints, such as telling them, ‘You need a certain amount of motors, you need to use a particular programming style, you need to connect to this code that we already wrote for you.’ But from there, they were free to design and build however they liked.”

I don’t think you’re going to find any class at Barnard that is purely science or purely art. I think that’s the nature of what we do here — everything is interdisciplinary.

With so much creative freedom, producing a computer-powered sculpture that could be activated from a cell phone wasn’t necessarily without challenges, especially because the project had so many metaphorical moving parts. Students had to program, work with hardware, and design an object that told a complete narrative. “The key benefit of this class was that it gave computer science students an opportunity to take ownership of creating artistic digital systems from the hardware to the software level,” explained Santolucito.

And students dug deep into their creative wells, spending as many as 40 hours on the sculptures over the course of the three-week project. “I enjoyed exploring aspects of mechanical and electrical engineering that I don’t usually see as a computer science major,” said Pazit Schrecker ’21, whose Carousel for COVID Times sculpture consisted of two motors, an ESP32 (a Wi-Fi and Bluetooth chip), a Raspberry Pi (a tiny computer), regular paper, card stock, cardboard, origami paper, a Lego wheel, a Lazy Susan, string, and a number of wires. “I like that I’ve been exposed to new types of problem-solving challenges and projects through this class, which helped me see how art and engineering can overlap and work together,” said Schrecker.

Yiyun Wang ’21, who made an automatic cat toy from her home in Wisconsin and lamented not having access to the soldering or 3D printing machines at the Design Center, said that facing limitations really inspired her to expand her scope. “I learned that it is always helpful to seek advice from my peers and the professor,” said Wang, who plans to attend graduate school for computer science. “Since the problems we could encounter usually don’t have a standard answer key — how to design my device or how to make things interesting — it is helpful to learn from different perspectives. I found that talking to people for five minutes is sometimes more helpful than staring at the screen and struggling for hours.”

Once the sculptures were completed, those who were local displayed their work in the Department of Computer Science’s lounge over the weekend of March 27. Similar to other projects in this embedded course, Santolucito said, the kinetic sculptures project was open-ended to encourage students to learn on their own.

“One of the nice things about Barnard, because we have such small classes, is that I’m able to do these sorts of open-ended assignments, so every student in the class got something out of it,” Santolucito explained. This “low floor, high ceiling,” as he called it, meant that because students had so many different cylinders firing — hardware, motors, software, coding — they had to use their imaginations to problem-solve.

“It’s building a foundation for students to continue to learn through their entire life,” Santolucito said. “So this class had elements of science and elements of art, and I don’t think you’re going to find any class at Barnard that is purely science or purely art. I think that’s the nature of what we do here — everything is interdisciplinary.”

The Creative Embedded Systems course, and other courses being produced under this umbrella, was funded by a grant provided by the Global Columbia Collaboratory, jointly founded by the Data Science Institute and Columbia Entrepreneurship.

If the pandemic has taught scholars anything, it’s that most things are interconnected, and STEM is oftentimes an anchor. That’s why Barnard’s Year of Science (BYOS) campaign, which runs throughout the entire 2021-22 academic year, will celebrate all things STEM and the increased interest in the field from Barnard students — 35% of the Class of 2020 were math and science majors, compared with 26% nationally, and 33% of the class’s underrepresented minorities were STEM majors, compared with the nationwide average of 23%.

To document a sample of the work that Santolucito’s students produced in his Creative Embedded Systems course, one student and three recent Barnard alumnae — Chianna Cohen ’22, Lucie le Blanc ’21, Pazit Schrecker ’21, and Yiyun Wang ’21 — shared their processes and their art in the above video.